Printing Your Own House

Interview with

Ben - Our next guest is building houses using a printer, or at least hoping to soon. Rupert Soar is from Freeform engineering where he uses computer aided design and rapid manufacture techniques to build walls and structures, essentially using a gigantic 3D printer! Hello Rupert, thanks ever so much for joining us...

Rupert - Hi Ben, Hi Helen...

Ben - So, Freeform engineering - who are you and what do you do?

Ben - So, Freeform engineering - who are you and what do you do?

Rupert - Well, essentially we do rapid prototyping, with a slight speciality in that we focus on the construction industry and in particular on those large scale elements where we're really printing big things.

Ben - So, 'Rapid Prototyping' - I'm guessing the name gives away what it is? It's for making a prototype very quickly...

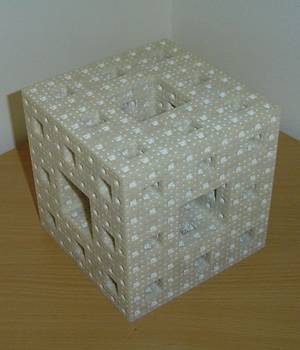

Rupert - Yeah, kind of. That's where it started. There's additive manufacturing, layer manufacturing, there's many different terms that are applied to this technology. All of them are essentially similar - taking your material, squirting it, pasting it down one layer at a time and building up a three dimensional object over time.

Ben - Now I would assume that normally this is used for things like new designs of mobile phones, or perhaps things that you hold in your hand.

Rupert - Absolutely, typically plastic things but, you know, small metal components, things that suit - mobile phones, automotive, aerospace, all very common.

Ben - But you're thinking of much, much bigger things?

Rupert - Yeah, in one level. Part of this is actually bringing awareness of what this technology is into the construction and architectural and design sector. And so trying to inform and bring about a news capability. Architecture itself is producing more complex designs and more interesting designs in the buildings that they see around them. They are able to generate amazing structures and forms in the computer and that challenge is then; how on earth do we actually fabricate those, how do we make them? They get stuck in the computer nowadays, these designs do. And so, these printing technologies just work layer by layer, printing one layer at a time and in fact there's no great magic involved - if you look at how any house is built its all bruit with layers of bricks. And the reason it's built with layers of bricks is that we can build the bits inside as well as the bits outside. So this technology is really cool because it allows us to print the really complicated stuff inside as well as everything outside.

Ben - Of course, and the complicated stuff usually would mean greater expense because it takes more time and more expertise...

Ben - Of course, and the complicated stuff usually would mean greater expense because it takes more time and more expertise...

Rupert - If you were talking about traditional engineering and manufacturing and trying to machine something out of a solid block, trying to get inside it is damn near impossible at the best of times, but you can really get into these structures and make them really complicated and do quite remarkable things.

Ben - One of the key things in buildings nowadays is all about using the right materials, and we've talked on the show before about things like thin layers of wax inside little capsules that melt when you get to certain temperature and then solidify again when and using this as insulation. Are you limited with rapid prototyping as to what materials you can lay down?

Rupert - Yes and no, like all things. There's no one ubiquitous process that does everything but essentially if you take your DeskJet printer and literally scale it in your mind, and instead of ink you're putting through cement or gypsum, let's say, then you're somewhere close to where we're going with this. It seems almost strange to think that you could squirt cement out and it wouldn't slump all over the ground, but that's because cement is used in moulds at the moment and concrete and it's designed to be sloppy. You take out those retardants and things like that and it starts to set quite quickly. So very, very quickly you can start to build up three dimensional structures - very, very big ones, if that is indeed what you're into doing.

Ben - I think you've given us a very good image of how it works, but I'm picturing a giant frame with an inkjet type head, effectively a bucket with a hole in the bottom that you control, that moves forwards and backward in three dimensions and releases your material as and where you need it.

Ben - I think you've given us a very good image of how it works, but I'm picturing a giant frame with an inkjet type head, effectively a bucket with a hole in the bottom that you control, that moves forwards and backward in three dimensions and releases your material as and where you need it.

Rupert - Yeah, if you've ever seen a large crane working in a shipyard, most people have got an image, that's a big crane and it's placing big things and that's kind of where this is going - large crane systems or gantry systems that can have deposition heads or squirty heads that are squirting stuff out and building them up; but that's a very simplistic level. As technology evolves then one very, very large machine very quickly becomes many, many small machines and then you're into autonomous robot swarms and all of that wonderful future that lies ahead for us.

Ben - It's a lovely idea that building sites might one day just consist of robots that get it over and done with really quickly, no wolf-whistling, no builders' bums...

Rupert - That's it. It's quite simple, you know, it's not hard to squirt things out and build things, ask anyone who has made a cake with icing sugar - it's dead straightforward. But getting it in swarms and connective agents and then you open up a whole new world of possibilities as to what you can build.

Ben - So effectively, because of the way that you can do this layer by layer; you can do the whole thing in one run. You don't have to print the outside walls and then take your machines inside and printing all the inside walls. You can actually just say - this is the design of house I want - go!

Rupert - Yes. The whole point of this is that traditional construction is a very hierarchical thing. You start by putting the superstructure and gradually with first, second, third fixing you come down in resolution, if you like, until you're literally fixing the screws and nuts and bolts into the structure and so its a very top-down approach. When you're printing a structure, and printing all the channels and ducts within the walls as well, you've essentially got to do the whole thing, all scales of resolution at the same time, so you've got to print fast to get your materials down but at the same time you've got to print fine to get all those little channels and ducts. And that's the key to it, as a friend of mine says - "The real estate of the future lies between the walls in our homes" those two surfaces. At the moment they're essentially solid, but very quickly we can engineer those walls and fabricate and essentially fold more functions into much, much smaller spaces. And that's the real key to where this drives forward.

Ben - This is fantastic stuff. How is the cost likely to compare to traditional building?

Ben - This is fantastic stuff. How is the cost likely to compare to traditional building?

Rupert - Cost - you can never compare what is essentially something that's been going for 2000 years - you know, I'm not going to beat a brickie, I was one myself and we can work fast. What this does is it enables other abilities, things that a bricklayer can't imbue into a building. So if you're laying bricks, let's use that example, then you're good with straight lines and squares and fairly uniform shapes. A printer, if you ask it to print a squiggly line or a square it doesn't care, it makes no distinction. Essentially you can print complicated structures and forms. There's no cost involved in how complex the structure is. Now that's a fundamental difference between how existing construction is and what it could be. So we're not usurping traditional construction by any means, we're just going to add to those capabilities. So a lot of the key discussions are about sustainable construction. Natural ventilation I know you've got covering in this programme, and what we're able to do is actually fold the structures and channels and functions into tighter and tighter spaces within these walls, and actually make and design structures that truly can capture energy from the environment. People know me for termites, I'm a bit mad like that but that's where we're going with that - walls as membranes and not barriers if you want a quick sound bite distinction there.

Ben - This all sounds fantastic and I hope that we'll see it in building sites in the very near future. That was Rupert Soar, director or Freeform Engineering explaining how one day you might just select the house you want, and print it out!

Comments

Add a comment