Science of Stargazing & Telescope Technology

Interview with

We invited Carolin Crawford to see what she thought of the telescope Dave built for

this week's Kitchen Science, then asked her how it compares to a real telescope...

Ben - Carolin, Dave has a very simple telescope but is this really what the first telescopes were like?

Carolin - It's actually a very good example of what the first telescopes were like and it's got the principle components you need. The first magnifying glass that Dave's got is the larger one. That's the one that collects all the light from things that are very faint. It makes them brighter. The second magnifying glass is what you need just to make that image bigger. It's supposed to be the principle component of any telescope we still use today.

Carolin - It's actually a very good example of what the first telescopes were like and it's got the principle components you need. The first magnifying glass that Dave's got is the larger one. That's the one that collects all the light from things that are very faint. It makes them brighter. The second magnifying glass is what you need just to make that image bigger. It's supposed to be the principle component of any telescope we still use today.

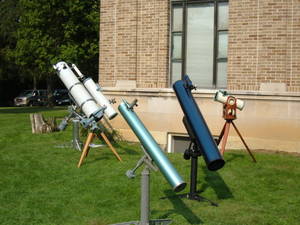

Ben - Does that include this enormous thing behind us? I'm assuming it is much more powerful?

Carolin - It is. The one we've got behind us is still quite old. It dates from 1838 but it's the same principle as Dave is demonstrating with his telescope. Instead of being a handheld magnifying lens it's actually one which is 12" in diameter. You can imagine that can collect an awful lot of photons from a distant source. The catch is to collect that and bring it down to a focus you need a tube that's just short of 20ft long. At the other end we have what we call the eyepiece. Really, that's just a glorified magnifier like Dave's second magnifying glass. We can change that around and get different magnifying strengths depending on whether we're looking for something that's small and star-like or large and fuzzy. You want different magnifications for different objects but the basic principle is very much the same.

Ben - How have telescopes moved on since these basic principles?

Carolin - Well, the kind of telescope we're demonstrating here is just one kind of telescope called a refractor. Most of the large telescopes today are reflecting telescopes. This idea was brought about by our own Isaac Newton, here in Cambridge. The idea here is that curved mirrors can have a lot of the same properties as curved lenses in the way that they will bend and bring light to a focus. The advantage of using mirrors is first, of all, the light gets folded up and gets bounced around between mirrors in the telescope. The telescope itself is a lot less cumbersome and a lot easier to move around. It doesn't have to be so long as a refracting telescope. There's a problem with these telescopes that use lenses in that you can only make the lens so big before it starts to sag in the middle. If you think of it you're holding it in place around the edges. If you get something that's appreciably more than 40" across the centre begins to deform under gravity and that distorts the images. If you want to go bigger you're really looking at using mirrors. They're much more reliable and they're much easier to make and transport. The very largest telescopes we use today all use mirrors. Those mirrors are all of the order of 8 - 10.5m across.

Ben - That sounds enormous. How do you make sure a mirror that size is exactly the right shape? I'd have thought it was so easy to go wrong and then ruin your entire telescope.

Ben - That sounds enormous. How do you make sure a mirror that size is exactly the right shape? I'd have thought it was so easy to go wrong and then ruin your entire telescope.

Carolin - The prime example of that is the Hubble telescope where they did get the curvature of the mirror wrong and there was a very big problem when it was first launched into space because all the images were out of focus. Usually we do test this quite thoroughly. There are also new and exciting experimental innovations which involve making mirrors out of segmented mirrors to mock up an even larger surface. There are many advances in how you use mirrors in a reflecting surface. It doesn't just have to be one solid mirror.

Ben - A lot of what is going on in space science now is not looking at visible light. Mirrors, lenses are very good at collecting visible light. How do we look at the things that we otherwise can't see? X-rays and microwave radiation?

Carolin - We're only talking about the visible side of astronomy and astronomy stretches right from gamma rays, x-rays, ultraviolet down to radio and infrared. Radio signals are collected on massive parabolic dishes. People may have seen that in terms of Jodrell bank and here in Cambridge, the radio dishes just outside of Cambridge on Barton Rd. There are special challenges when you want to take pictures in the UV because atmosphere blocks out the light. That has to be done from orbit. You get some really exciting challenges from x-ray astronomy because x-ray photons have so much energy in them they would just slam into the surface of a conventional optical mirror. You can only bring them into focus if you put the mirror edge-on to the x-ray photons. It sort of ricochets off the mirrors and is brought into focus that way. If you looked at an x-ray telescope it would look nothing like the one Dave's got here. It would be a set of nested cylinders collecting photons and bringing them to a focus at the end of the cylinder. There's a huge variety of ways that astronomers use telescopes to do their astronomy.

seen that in terms of Jodrell bank and here in Cambridge, the radio dishes just outside of Cambridge on Barton Rd. There are special challenges when you want to take pictures in the UV because atmosphere blocks out the light. That has to be done from orbit. You get some really exciting challenges from x-ray astronomy because x-ray photons have so much energy in them they would just slam into the surface of a conventional optical mirror. You can only bring them into focus if you put the mirror edge-on to the x-ray photons. It sort of ricochets off the mirrors and is brought into focus that way. If you looked at an x-ray telescope it would look nothing like the one Dave's got here. It would be a set of nested cylinders collecting photons and bringing them to a focus at the end of the cylinder. There's a huge variety of ways that astronomers use telescopes to do their astronomy.

Comments

Add a comment