The Secrets of Odysseus

Interview with

Chris - Most of us have heard the tales of ancient Greece and the majority of the time we just think of these tales as another good story but there's now a team of classicists and scientists who think the story told in one of the most famous of those ancient Greek myths, the Odyssey, might actually be based on a lot more fact than fiction. To explain how they've been doing this they've been looking into this 3000 year-old mystery as a group. We've got the University of Edinburgh's Professor John Underhill and we've also got Robert Bittlestone who's a businessman who also has a background in the classics and is the author of a book Odysseus Unbound, by the way. We also have Professor James Diggle. He's the Professor of Greek and Latin at Queens' College. James, why don't you kick off by telling us a bit about the background to this mystery?

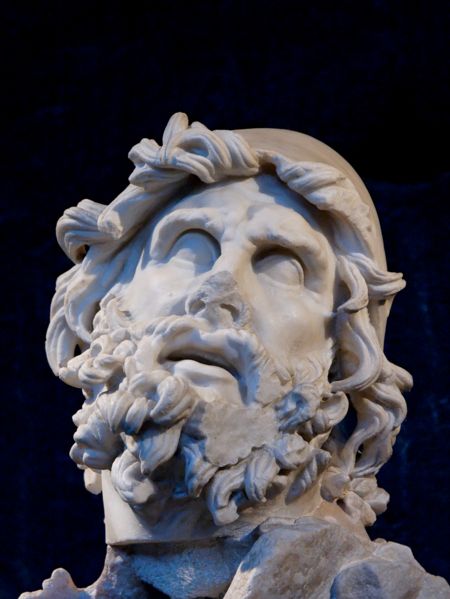

James - Right at the beginning of European literature there stand these two great epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The Iliad tells the story of the Trojan War, the Odyssey the story of Odysseus: king of the island of Ithaca and also of Troy. The Greeks believed that these two poems had been written by a poet they called Homer. Almost certainly no such poet as Homer ever existed. The poems as we have them were written some time between 800 and 600BC but they have their origins many centuries earlier. They're examples of a kind of poetry we know as oral poetry. That is, poetry that was not composed with the aid of writing but was composed in the minds of poets or bard singers, as one might call them, who were composing their verses off-the-hoof: extempore before live audiences, developing the work of their predecessors and in turn transmitting it to their successors. Generation after generation of these oral poets creating a vast body of oral verse which eventually got written down and of which the only two surviving examples are our Iliad and Odyssey.

James - Right at the beginning of European literature there stand these two great epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The Iliad tells the story of the Trojan War, the Odyssey the story of Odysseus: king of the island of Ithaca and also of Troy. The Greeks believed that these two poems had been written by a poet they called Homer. Almost certainly no such poet as Homer ever existed. The poems as we have them were written some time between 800 and 600BC but they have their origins many centuries earlier. They're examples of a kind of poetry we know as oral poetry. That is, poetry that was not composed with the aid of writing but was composed in the minds of poets or bard singers, as one might call them, who were composing their verses off-the-hoof: extempore before live audiences, developing the work of their predecessors and in turn transmitting it to their successors. Generation after generation of these oral poets creating a vast body of oral verse which eventually got written down and of which the only two surviving examples are our Iliad and Odyssey.

Chris - Is the fact that they were writing it down why they used poetry? Because there are so many rules to how you create poetry was that a way of making sure the meaning was faithful?

James - Absolutely. This is a reason why you can get things that were in existence, say in Mycenaean times (1200BC) still being accurately reported, transmitted 600 years later because the oral poets used formulaic phrases which got fossilised in poetry. Once you developed a description of a place or an artefact there's no reason to change it.

Chris - If you did change it the rhyme or the meter would be wrong so they'd know that something was adrift.

James. Absolutely. There was a very strict meter.

Chris - How do we turn this on these ancient texts, the Odyssey and the present situation you find yourself in where you're in this 3000 year-old mystery?

James - Yes, we're focussing on the Odyssey. Specifically the location of Odysseus' island Ithaca. Where was it?

Chris - It still exists, doesn't it?

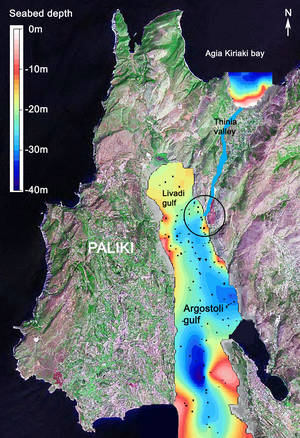

James - Well, it would seem to many people to be a very strange question to be asking. There is indeed an island which the Greeks call Ithaki and we call Ithaca. Let's just focus on the part of Greece that we're talking about. We're talking about the West coast of Greece, that is the coast that faces Italy. Halfway up that coast, right below Corfu there's a group of three islands: Ithaki, Zakynthos and perhaps the one that's best-known of all, Kefalonia from Captain Corelli's Mandolin.

Chris - What's the big question? Why do we doubt that when we're calling Ithaki Ithaca that's what we think it really is?

James - The text of the Odyssey gives us three very clear indications on where Ithaca is and what kind of island it was. These are they:

James - The text of the Odyssey gives us three very clear indications on where Ithaca is and what kind of island it was. These are they:

First of all, the Odyssey tells us that Ithaca is in a group of four islands but modern Ithaki is one of three. Secondly, the Odyssey tells us that Ithaca is the farthest West and the farthest out to sea of these islands but Ithaki is the closest East and closest to the mainland. Finally, the Odyssey tells us that Ithaca is low-lying - that it hasn't got any mountains but Ithaki is a mountainous island with cliffs plunging sheer into the sea.

Chris - So the big question is, was the poet just using artistic license when he wrote that and just thought, "Well, it doesn't really matter."

James - You've got two options. That is one. The other is to say we simply haven't found the correct island. Given that we have found other places that are mentioned in the heroic poems like Troy and Mycenae (these have been excavated) we know that they existed. There's therefore reason to believe that the poet described in great detail Ithaca he was talking about a real island.

Chris - Let's bring Robert in. Robert, when did you have the insight that actually we might be on the trail of the wrong island here?

Robert - I was fascinated by the description that James has just given us. Here is an ancient poet describing a world in which his crucial island, the island of his hero, is farthest out to sea, farthest West, low-lying and so forth. When I looked at the map it was actually in the context of planning a family holiday some years ago. I thought, 'how can this be?' How can somebody get it not just marginally wrong but really, really wrong? I wondered, as you suggested, about the explanation that many, many scholars have suggested in the past. Was the reason for this that he just didn't know or he didn't care and he was writing a poem after all, not a travel guide? It seemed to me that that didn't really hang together at all. The reason is it's a motiveless crime to mis-describe your crucial island in such a way. That is to say, either you do know where it is or you don't. If you do know where it is there's no reason for you to mis-describe it. If you don't know where it is why describe it so specifically but incorrectly? The very first time you recite these lines to a bunch of sailors, and Greece is a small place, they're going to say, 'Rubbish! It's not there, it's over here.' It would be like somebody today writing a play which their lead character says without any sarcasm, 'Oh I come from New York: a beautiful city built on a steep hill on the West coast of America.' It's just going to get contradicted and corrected within a very short time with its composition. That's what drew me in. I thought this is a motiveless crime. There must be a different explanation.

Chris - What did you come up with as an alternative suggestion?

Robert - The alternative suggestion was this: there is clearly this major contradiction between how the poet describes Ithaca and the Island that is today called Ithaki. My though was to say instead of assuming that everybody seems to be that the reason for the discrepancy is that the poet made a mistake what about the alternative that at the time he composed these lines, supposing they were absolutely accurate but something has happened since to change the landscape? That was the, if I can refer back to your earlier material, Eureka moment!

Robert - The alternative suggestion was this: there is clearly this major contradiction between how the poet describes Ithaca and the Island that is today called Ithaki. My though was to say instead of assuming that everybody seems to be that the reason for the discrepancy is that the poet made a mistake what about the alternative that at the time he composed these lines, supposing they were absolutely accurate but something has happened since to change the landscape? That was the, if I can refer back to your earlier material, Eureka moment!

Chris - A good time now to bring in John Underhill who is the Professor of Geology at Edinburgh University. He's involved in this. Would this sit with you as something that could be a possible explanation for what was going on here?

John - Yes. I first got involved with the geology of western Greece back in the 1980s when I did a PhD there. Although Thinea, this key valley that we focussed upon wasn't a primary area as part of that it was one where I had interest and had looked at. When the opportunity materialised to get involved in the project I thought it was worthwhile given that it was a very interesting theory but inherently testable. To be honest I thought at the time that it would be easy to refute. Easy to disprove this particular theory. That's easy to say from Scotland. When you go out into the field it actually proved much more hard to disprove the theory that Robert and James have come up with and just given to you on the ground.

Chris - What they're basically saying is that there's been some massive ground movement which has made what was four islands become three islands. One of them is the original Ithaca.

John - Yeah. The western peninsula, Peliki is very low-lying. There is a narrow valley called Thinea which separates it from the main part of Kefalonia. If that particular valley were once underwater and we're talking 3000-2000 years ago because there are two independent references: one that James has referred to, Homeric text of the Odyssey. The second is that Strabo, the first geographer 2000 years ago (around the time of Christ he was writing) actually says that there is a narrow isthmus where Kefalonia is narrowest. From time to time, not always, it saw waters going from end-to-end. We know very specifically where he was describing because there are two Roman settlements that he mentioned within his text. They both lie on either side or at least the areas which they governed lay on either side of this valley. The theory is very challenged in this valley. We should not underestimate that. The valley itself rises to over 175m at the present day in the central saddle area. The work that I've undertaken around the coastlines of Kefalonia indicate that we cannot have recourse to uplift alone despite the seismicity; the earthquakes recurrence in the area. Wave-cut notches and raised beaches in the area show us that uplift is insufficient. We must appeal to other processes.

Chris - What you're saying is that we can't just say the land has risen to join these islands together. There must be something else going on?

John - That's correct. In this particular area which we know to be the earthquake hotspot of Western Europe it lies at the boundary between the Eurasian and African plates. Cephalonia is, in fact, the seismically most active part of Greece. As the earthquake earlier today in western Greece (6.5 magnitude in western Greece) testifies this is really one of the most active areas in the world, let alone Europe.

John - That's correct. In this particular area which we know to be the earthquake hotspot of Western Europe it lies at the boundary between the Eurasian and African plates. Cephalonia is, in fact, the seismically most active part of Greece. As the earthquake earlier today in western Greece (6.5 magnitude in western Greece) testifies this is really one of the most active areas in the world, let alone Europe.

Chris - What have you done to test the hypothesis that these four islands have become three?

John - The first thing we did was ground geology. We mapped the area and it was clear from a very early stage that the surface geology is insufficient to test the theory rigorously. You need to look beneath the ground. What you can see on the ground in the area is that there is massive landslide and rock fall debris strewn across the valley surface. Large boulders the size of houses, trucks and the like which as we know from the August '53 earthquake, which was depicted in Captain Corelli's Mandolin of course, there were catastrophic failures of whole hillsides at that time. They've been captured on film and are in the record.

Chris - So you think there was a big landslide potentially that could have filled in the gap which previously was covered by ocean but filled in now by debris from a landslide? Does this mean then that you could find out historically is such a landslide existed?

John - Only by looking under the ground. I think we would be foolish to think it was a single landslide. Catastrophic landslides occur regularly within this area. Indeed in November of last year without an earthquake attached to it a village, Nifi, was swept away unfortunately after a major landslide from the eastern slopes of Thinea. Tests of the principle we are looking at.

Chris - But you've done some drilling, haven't you?

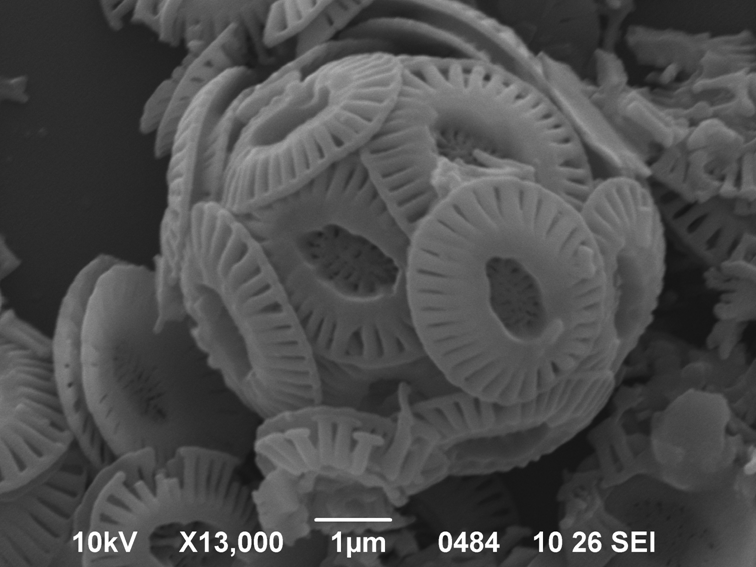

John - The first borehole that we drilled was back in Autumn of 2006. It was located on the eastern side of the valley. We drilled down from a surface elevation of 107m. We drilled down 122m so below sea level. Interestingly, that borehole found rock fall debris extending at least 40m below the current land surface i.e. 67m above present sea level. Most importantly the matrix to that borehole contained large boulders of cretaceous and other limestone material derived from the eastern slopes a very young fossil called Emiliana Huxley, a marine fossil that is 80,000 years or younger. Actually within this area we know marine waters only reached the region within the last 5000 years. A very interesting result.

Chris - Robert, this must be extremely pleasing to you.

Chris - Robert, this must be extremely pleasing to you.

Robert - I have learnt that one shouldn't get too excited too soon as new bits of evidence come along. I think on the scale of things this is a tough geological challenge. I'm sure John would agree this isn't something that can be solved by a field study for a couple of weeks. Yes, it was very exciting after that autumn drill hole when the borehole went right the way down, didn't encounter any solid limestone. It encountered material that made us think with the possibility of an enormous rock fall event or series of events came thundering down the mountainside, hit a body of relatively shallow sea water and in the process of that perhaps thrust much of that water up into the air in such a way as to interpenetrate all the debris coming down and end up with all these tiny nanofossils. That's one possible mechanism and there are other mechanisms but what we are finding as this work is done nothing John's saying is, 'That's it. End of theory it's impossible.' It's tough to interpret the data. It takes a lot of work, a lot of resource and fortunately a lot of industry support that we're now getting to the project.

Chris - James, you must be really pleased that this has come to this point but what do you think is going to be a next step from your classics point of view?

James - I think what I find so wonderful about this is that it mixes together a whole variety of disciplines. My particular interest is on the literary and historical side but it blends with that archaeology, geology, science of various kinds, mythology - just about everything. A wonderful multidisciplinary activity that we've got ourselves involved in but if we can just go back to Troy and Mycenae. Troy was believed once upon a time to have never existed. Heinrich Schliemann discovered it in the 1870s. Mycenae was then excavated. Now we think we're on the brink of demonstrating that Odysseus' civilisation, palace on Ithaca existed too.

Visit the project website: http://www.odysseus-unbound.orgRead about the discovery: http://www.odysseus-unbound.org/book.html

- Previous Finding Forgotten Fingerprints

- Next Seeing Secrets Underground

Comments

Add a comment