The Use and Abuse of Statistics

Interview with

Chris - We're now joined by Ben Goldacre. Tell us a bit about what you'll be talking about because you'll be joining us at the Science Festival to give a talk about some of these things. What are you going to cover in your talk?

Ben - You've just reminded me, I need to write one. I am going to write about the various different ways that people who really should know better make mistakes with statistics. Not the kind of easy ways that everyday people are fooled but people in senior roles in government and medicine and industry and the media and that kind of stuff.

Ben - You've just reminded me, I need to write one. I am going to write about the various different ways that people who really should know better make mistakes with statistics. Not the kind of easy ways that everyday people are fooled but people in senior roles in government and medicine and industry and the media and that kind of stuff.

Chris - We've heard the phrase 'lies, damn lies and statistics.' This is not a new phenomenon so there must be some fantastic examples that you can showcase your talk with.

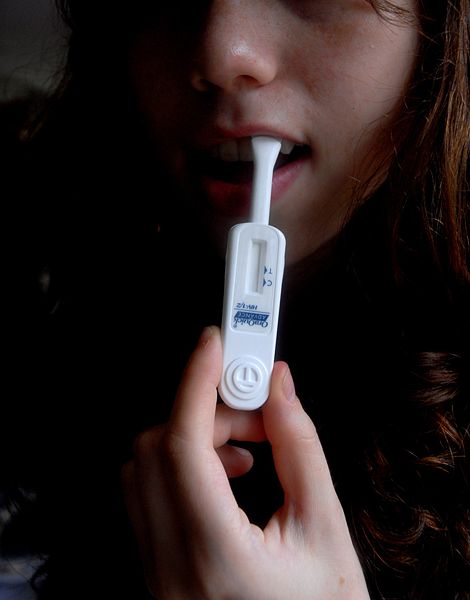

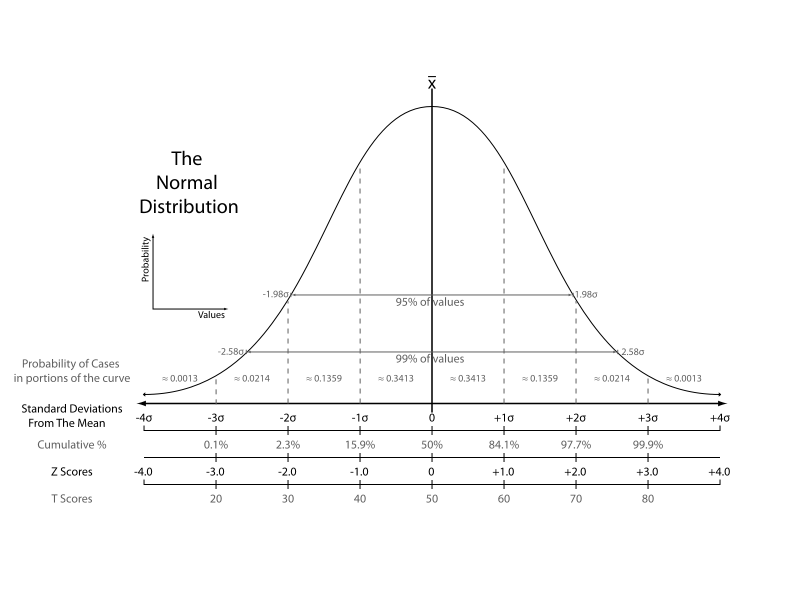

Ben - Yeah and the interesting thing is that the same problems keep coming up time and time again. For example, screening is a very interesting issue. People are often, I think it's because it's attractive to think well, surely doing something is better than nothing - to imagine that screening could be useful way of firstly detecting breast cancer in people where breast cancer is very rare. So outside of the current screening window of women over 55. Also perhaps screening, as MI5 suggested recently, everybody's computerised communication records to spot terrorists or screening everybody for AIDS. The interesting thing is, when you're trying to screen for something that's very rare, like being a terrorist or having AIDS, actually you're false positives start to outweigh your true positives. Even if your test is very good.

Chris - Let's just define that. False positives are, of course people you accuse of being a terrorist and they're completely innocent.

Ben - That's right. It works best with a concrete example. If we take AIDS, let's say we've a really brilliant blood test for HIV. It will only give you a false positive in somebody who doesn't have HIV: one test out of every 10,000 that you do.  That's a very good test if you're doing your HIV tests on a population where people are fairly likely to be HIV positive. Let's say injecting drug users or perhaps gay men with a long history of unprotected sex. You might say the risk in that population is 1 in 100 and your risk of a false positive with each test is 1 in 10,000. In general if you get a positive HIV test in someone like that then it probably means they really do have HIV. Then if you do the same test on members of the general population who have a very low risk of HIV, let's say the general population in Britain your risk of having HIV is probably 1 in 10,000. If you're doing your test in a population where only 1 in 10,000 people have HIV and your test gives you a a false positive for 1 in every 10,000 tests that you do then actually a positive blood test is only going to mean that the person genuinely has HIV half the time.

That's a very good test if you're doing your HIV tests on a population where people are fairly likely to be HIV positive. Let's say injecting drug users or perhaps gay men with a long history of unprotected sex. You might say the risk in that population is 1 in 100 and your risk of a false positive with each test is 1 in 10,000. In general if you get a positive HIV test in someone like that then it probably means they really do have HIV. Then if you do the same test on members of the general population who have a very low risk of HIV, let's say the general population in Britain your risk of having HIV is probably 1 in 10,000. If you're doing your test in a population where only 1 in 10,000 people have HIV and your test gives you a a false positive for 1 in every 10,000 tests that you do then actually a positive blood test is only going to mean that the person genuinely has HIV half the time.

Chris - What should we do about this? How should this alter our practise? What should we do to make sure we don't end up pursuing false leads statistically like that?

Ben - I guess what it means is you have to be very cautious about where you employ screening and whether you think it's a good idea or a bad idea. It depends on the maths of individual cases. Just recently the ex-head of MI5 wrote a report for, I think, IPPR. It got a lot of press coverage. It said, maybe we have to accept that the security services should have access to everybody's computerised records. Everybody's text message communication patterns, the lists of whom they phone, access to the contents of their emails, their tax records, their travel records, all of this stuff. Then we can use pattern-spotting software to try and identify who is a possible terrorist subject and who isn't. That sounds superficially quite appealing. You could make a case if it was true that was likely to spot terrorists. You could make a case. You could say maybe it was worth sacrificing our civil liberties and our privacy in order to catch terrorists. That's a separate argument, a moral argument. Before you even get there you have to be clear on whether screening is capable of spotting terrorists in the general population.

Chris - That's one of the criteria for screening. We say when we're screening for something, if we can't actually detect it effectively or do anything about what we find. We just don't screen for it.

Ben - Absolutely: There are two problems with screening for terrorists. One is that terrorism is extremely rare. There are probably  10,000 likely terrorist suspects in the UK, waiting to do something. In reality it's probably much lower than that. Then you've got to think, what's you r test for spotting a terrorist? Our tests for spotting HIV in blood are really good. They're only wrong 1 time in every 10,000 which means they're right 9,999 times out of 10,000. That's an amazingly good test and that still falls over when you're looking at something very rare. Your test for spotting whether someone's a terrorist from looking at their telephone records are going to be much less accurate than that. They're going to be much less accurate in the two important ways that a test can be flawed. First of all, they're going to be quite likely to miss true terrorist subjects but they're also going to be quite likely to falsely identify people as terrorist suspects when they're actually not. If you run the maths you'll see that even a test which is 99% perfect is unimaginably good. We'll still identify thousands and tens of thousands of people as suspects which is basically useless. It's worse than old--fashioned trade craft and investigation techniques. What are you going to do with 10,000 possible suspects to try and investigate all of those people in any detail is obviously impractical.

10,000 likely terrorist suspects in the UK, waiting to do something. In reality it's probably much lower than that. Then you've got to think, what's you r test for spotting a terrorist? Our tests for spotting HIV in blood are really good. They're only wrong 1 time in every 10,000 which means they're right 9,999 times out of 10,000. That's an amazingly good test and that still falls over when you're looking at something very rare. Your test for spotting whether someone's a terrorist from looking at their telephone records are going to be much less accurate than that. They're going to be much less accurate in the two important ways that a test can be flawed. First of all, they're going to be quite likely to miss true terrorist subjects but they're also going to be quite likely to falsely identify people as terrorist suspects when they're actually not. If you run the maths you'll see that even a test which is 99% perfect is unimaginably good. We'll still identify thousands and tens of thousands of people as suspects which is basically useless. It's worse than old--fashioned trade craft and investigation techniques. What are you going to do with 10,000 possible suspects to try and investigate all of those people in any detail is obviously impractical.

Chris - People who cast their mind back about ten-fifteen years will remember something called the Cleveland child abuse scandal which was precisely this. It was a flawed test which basically caught just as many people who were innocent as guilty and led to lots of people being accused of child abuse, and being abused, who hadn't.

hadn't.

Ben - Is that right? I know nothing about that, sorry.

Chris - It was a major issue with people applying a test which was very flawed in the sense that it was pulling out cases, some of which had been abused but many hadn't. It led to great amounts of heartache for the reasons you've outlined. It's very difficult to be accurate and specific with these kinds of tests. Let's wind this up by you telling us what you'd like to see done about this.

Ben - I guess a lot of the time discourse on screening is driven by politics and emotion. For example, politicians will want to say we're doing something useful about breast cancer or heart attacks or stroke or whatever. We're having a big screening programme. That feels like a really positive thing to do and it's the same with screening for terrorism. It's the same for screening for all kinds of things. I think people do just have to be rational about it and think through the figures. On the one hand there's the practical outcome that you want. On the other I actually am nerdy enough to think that the maths on screening is quite interesting in and of itself. That's good enough for me.

Chris - But you don't have to be a geek to go to Ben's talk. He's at the Cambridge Science Festival this week if you want to catch up with him.

Ben Goldacre is also the author of the

popular book, Bad Science.

Comments

Add a comment