Why we don't bite our tongues too often

Interview with

Why when we speak or eat do both sides of our jaw move? Chris Smith put this question to Fan Wan from Duke University Medical Centre, Department of Neurobiology.

Why when we speak or eat do both sides of our jaw move? Chris Smith put this question to Fan Wan from Duke University Medical Centre, Department of Neurobiology.

Fan - So, the question we had in mind is, how do we use our muscles in our face and mouth in a highly coordinated manner? For example, when you eat banana, your tongue is trying to position the banana between your teeth and your teeth are chewing it down. Once it's grinded into a mushy bolus, you're automatically using other muscles in your throat to swallow it, without much effort.

Chris - And I suppose that the additional complexity is that these are muscles that are paired because you've got one set on one side of your face, one on the other and they've got to move together in order to move your jaw symmetrically.

Fan - Yes, exactly. So, mammals have their jaws, a lot of them fuse in the midline. So, if you try to chew on one side, the other side automatically also move together.

Chris - So, one therefore has to ask, do they work in that coordinated way because there are connections between the nerves that supply those individual muscles at the level of the brainstem where those motor nerves originate? Or are there signals coming down from above higher centres up in the brain which are activating them together so that you get a coordinated movement?

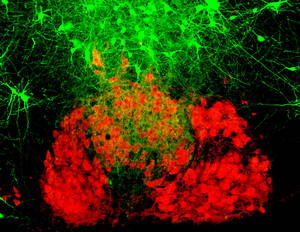

Fan - Precisely. So, we actually took a relative naive approach. We wanted to see what neurons are connected to the different motor neurons. So, we use a virus that can infect from the muscle and to the motor neurons that sort of supplies the muscle, controls the muscle. And then the virus can replicate itself in the motor neurons then jump to other neuron that connect to these motor neurons. So, while we did such studies for the jaw muscles and the tongue muscles, when we labelled the neurons connected to one group of motor neurons, we found those neurons also send axons to another additional group of pre-motor neurons. What we find are the pre-motor neurons have one branch connected to the left side of the jaw muscle. The other branch connect to the right side of the motor neurons that control the right muscle, thereby, providing a simple solution to synchronise the left and right side.

Chris - So, does this mean then, if I were to go in and deactivate those pre-motor neurons which are effectively the coordinators of this movement on one side of a brain stem, just if I deleted them or took them away. Animals should still be able to activate the muscles co-ordinately on both sides of their face because the other side would nonetheless turn on the right groups of motor neurons in the right order.

Fan - Exactly. I think that's our prediction. We're actually trying to do the exact experiment that you just proposed.

Chris - Probably the most important question of all, have you discovered why we do or don't bite our tongues? Sounds like a slightly fastidious question, but actually, it's an important one because tongue movements are very highly coordinated with chewing movements, aren't they, because otherwise, we would be lopping off our tongues every time we had a meal.

Fan - Exactly. There are two aspects. Neurons that control the motor neuron of our tongue sticking out are always simultaneously controls at the door opening motor neurons. In a sense that when you're sticking your tongue out, you are obligated to open your jaw. And that is a simplest mechanism to ensure you don't close your jaw but bite to your tongue.

Chris - What have you actually found though that is genuinely new here? Because when one goes and looks at a patient who's had a stroke, medical students and doctors look at the patient and ask them to say, raise their eyebrows or smile because this can distinguish between whether they've got damage to the lower motor neuron or the message not getting through from above. It's well-known that if you damage the brain stem, the motor neurons, you will be paralyzed on one side of the face. But if the upper motor neuron is damaged, you can still nonetheless make these symmetrical bilateral movements.

Fan - Good point, yes. So especially in the brainstem, it seems there are

promoter neurons. A lot of them do have bilateral projections although it's a ipsilateral or one side sort of a concentration, a bias. Previously, people find are, you can stimulate one side of the cortex, this is done in animals, and then you can initiate bilateral synchronised movement of the jaw. However, when you cut the midline of the brainstem, you will lose this ability to synchronise the jaw movement. You need some sort of connections across the midline at the brainstem for bilateral synchronised jaw movement.

- Previous Eczema prevents skin cancer

- Next Freeze drying blood!

Comments

Add a comment