Trump's Treatments & Nobel Prizes

This week Chris is joined by top palaeoanthropologist Lee Berger and BMJ executive editor Theo Bloom to dissect the science behind the headlines. As Donald Trump recovers from his coronavirus infection, what experimental treatments has he received, and what have we learned about managing COVID since the pandemic started? The Nobel Prizes are out: who’s won what? And David Attenborough’s new film has launched; we talk to the executive producer...

In this episode

00:57 - Publishing COVID, and a new hominid

Publishing COVID, and a new hominid

Lee Berger, University of the Witwatersrand; Theo Bloom, BMJ

Chris Smith was joined by two featured guests: Lee Berger, one of the world’s leading palaeoanthropologists from the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa; the executive editor of the British Medical Journal Theo Bloom...

Chris - Lee, I think it's actually this year, 13 years almost to the day since we first met in Johannesburg. 13, unlucky for some but definitely not for you: I gather that you've discovered not one, not two, not three, but now four new species of ancient human ancestor?

Lee - It's only three new species so far! We'll work on that though with these new discoveries... I'm in the middle of a discovery right now. COVID kind of pushed us into a strange space. I had to figure out something to do when we could get back once our lockdown levels and COVID actually lowered here in South Africa; and I'd already dispersed my laboratories. And there was this site that we had discovered early on in the exploration activities back in 2013; and it was a difficult site, it was going to be a site that was hard to work, it was going to be a site that had every reason - it was dangerous - that I didn't do it. And I decided to take a chance on it. Day one, we hit an extraordinary discovery that we're in the middle of right now. And so this is really the third big discovery that we've had. It's full of hominids, and we're very fortunate to be able to work under these conditions.

Chris - So this is a cave site. Is this where Homo naledi - the smaller ancestors that were burying their dead - came from? Or is this a different site?

Lee - This site's 200 meters away from where we discovered Homo naledi. It's a different cave system; it was right in front of us. It's an entirely different kind of creature from homo naledi: it's a big toothed hominid. It's extraordinary.

Chris - And how old is this?

Lee - I have no idea. This whole discovery is three and a half weeks old.

Chris - Well you heard about it here on The Naked Scientists first! Theo, over to you for a second. What has it been like running a medical journal during COVID? We've heard from Lee what it's like to try and do field work and actually make extraordinary discoveries and leaps forward. What's it been like at the BMJ?

Theo - Busy is the one word that comes to mind. I mean, we probably... most medical journals have seen a ten to a hundred fold increase in submissions of papers, with people very anxious to get out their latest findings about COVID, and we've had to scale up to handle those. And of course we've been trying to get results out very quickly if they're important; the public needs to know as soon as possible. So we're working around the clock. And a lot of my colleagues are working at home with small children and nevertheless trying to do more hours than they ever did before. It's a busy time.

Chris - Has it been a mixed bag in terms of the quality of what you've received? Have you received some stuff that you think “my goodness, that's amazing,” and have you also received some stuff that makes you go, “my goodness, I can't believe someone actually sent that to a journal, did their toddler write this?”

Theo - Yes, we pretty much always get a range of quality. I think what's happening now though is that everyone thinks every single finding about COVID is really, really important. And they want to get it out as fast as possible, maybe when it's not quite ready.

04:16 - COVID critical care: what we know now

COVID critical care: what we know now

Charlotte Summers, Addenbrooke's Hospital

When Donald Trump caught the coronavirus his doctors put him on a range of treatments, including an experimental antibody therapy from the company Regeneron as well as a number of other drugs and supplements. It’s been unclear how ill he actually is, so it's difficult to judge whether these measures were appropriate; but how do they stack up against the current best practice in COVID treatment? And how much have we learned since the pandemic began? Charlotte Summers is an intensive care consultant at Addenbrooke's Hospital; she also advises the UK government on managing the condition. Chris Smith asked her opinion on Trump's treatments...

Charlotte - I have to say I was quite surprised; they perhaps weren't the first drugs necessarily that I would have reached for had I been one of the doctors looking after him. I think the most controversial is probably the Regeneron therapy that he had, which is a cocktail of two antibodies that are designed to neutralise the virus. And actually the company that makes those had only released the first data on this a few days before they were given to the president, and it was only based on 275 patients, and the clinical trials are ongoing. We don't actually know whether this therapy works or not. So I was slightly surprised that a very experimental therapy - which although it looks promising, isn't proven - was given to the president of the United States.

Chris - The rationale for using antibodies is, of course, that's what your own immune system makes when you have an infection; and if you give people those, perhaps it will help to soak up some virus and bolster your own immune response. Have we not though seen something of a checkered response to the convalescent plasma therapy that has been done for some time since this began, where people are taking blood products from people who have recovered from coronavirus and giving them to people at high risk of severe disease, and it's not clear that that's actually working? So why do we think these Regeneron... or I know AstraZeneca are also making a rival product, aren't they? Why do we think that this is actually worth pursuing?

Charlotte - The issue with convalescent plasma is that everybody makes a different level of immune response. Some people make a very low level of antibody response; some people make much higher. And lots of the data that's been generated with convalescent plasma studies has not been terribly clear about the amount of antibodies in the therapy that's being given. But convalescent plasma has been given by two big trials in the UK that are ongoing at the moment, the RECOVERY trial for people who are hospitalised and the REMAP-CAP trial for people that are in intensive care. So we should get an answer from those fairly soon, I hope. The antibody therapies: we know how much antibody you're given, and we know that they are targeted to try and neutralise the virus, so it's slightly different type of antibodies to the general antibodies you might make in your new plasma in response to having had the virus.

Chris - So there's a slightly higher prospect that they may be advantageous. The other thing that he got was dexamethasone- tell us a bit about that.

Charlotte - Dexamethasone is a steroid treatment and that's quite widely used across a range of healthcare settings. But what was important was that this therapy is one that's got an evidence base. The big UK clinical trial called RECOVERY, that lots of people will have heard of, showed that there was a mortality benefit in people who needed oxygen or who were on ICU ventilators if you were given dexamethasone; so their outcomes and their chance of survival were improved by having this therapy. People who weren't on oxygen: there was definitely no benefit, and possibly even a potential that the therapy did some harm in that group of people. So I can't imagine that they gave the dexamethasone therapy to Donald Trump without him requiring oxygen. And we know that the reports about whether he did or didn't require oxygen have been a little bit confusing at times.

Chris - Theo, you must have been party to quite a lot of data coming across your desk on drugs, including dexamethasone?

Theo - Yes. I think at the moment there are several hundred trials of different drugs and therapies ongoing, and there's also been a lot of claims based on observation, because so many people have been hospitalised and some of them happen to be taking drugs for something else. For example, there was a suggestion that one particular antacid that people take if they have stomach problems... people taking that in China, in the first wave of COVID, appeared to do slightly better than people who weren't taking it. And actually that's one of the cocktail of drugs that Donald Trump seems to have been given, although he may have been taking it anyway.

Chris - This is famotidine, isn't it? The ranitidine-like drug?

Theo - Yeah. But he may have been taking that anyway for some other condition; we don't know. They seem to have sort of thrown a bunch of things at Donald Trump, some of which, as Charlotte said, you would expect to treat severe illness with; and some, like the antibodies, you would treat early in the illness; and it just adds to this confusing picture of how long he's been ill, how seriously ill he was.

Chris - And Charlotte, if you had been the physician to Donald Trump and you had to treat him or manage him, how would you have approached it? And also what have we learned about how, when someone comes in and they're acutely unwell with COVID, the actual disease caused by this virus, how we manage them now, compared to how we would have been managing people back in March?

Charlotte - It's slightly tricky to say exactly how I'd have managed him and get it right, because I don't have all of the medical information available to me. I've just got what's in the press. But I would definitely have started with the therapies for which we've got evidence. So if he needed oxygen, I would definitely given him the dexamethasone. And if he was early on, and had signs of pneumonia - inflammation in his lungs on a chest X-ray - I would have given him remdesivir, the antiviral therapy, that he did get, but a little bit later and after getting the Regeneron. And given that convalescent plasma actually has got an emergency use license in the United States, I would potentially have gone with that rather than the experimental Regeneron therapy. Although I would have tried to encourage him to be randomised into a clinical trial so that actually we could have learnt something about the use of these therapies, rather than just giving it on compassionate grounds.

Chris - What about issues with giving people supplementary oxygen early? And also this question about anticoagulation? We've learned, have we not, that quite a lot of people who get this infection have problems with their blood clotting going off?

Charlotte - I'd have given him oxygen if he needed oxygen. And actually there's advice across the world about the levels at which we should start giving people oxygen therapy that vary from between about 90 to 94%, depending on how well you're monitored. So if his oxygen levels had dropped to those kinds of levels, I would absolutely have given him the oxygen, because that's important. Anticoagulation is more tricky and there's actually not strong consensus across the community of hematologists and other healthcare researchers about what the best approach is here. We know that patients with sepsis from any cause actually have an increased risk of getting blood clots. And coronavirus infection, or COVID-19, has had a really big number of people with a sepsis type illness recently. So we've been seeing a lot of people with blood clots, but it's still not definite that the proportion of people with COVID getting blood clots is substantially greater than the people who have sepsis from other causes, but I think it probably is. But we don't have data to back that up.

In terms of what we do about that, there isn't an evidence base to answer that question at the moment. There's an arm of a trial called REMAP-CAP that is looking at hospitalised ward patients in the UK to try and come up with an answer for that. And there are other trials in discussion across the world. But it's something that we don't have good evidence for. Should we give them things like aspirin? Should we thin the blood therapeutically? Should we just give them protection against developing clots? What's the best way to go? It's still a subject of great debate.

13:48 - Nobel Prizes 2020: who's won what?

Nobel Prizes 2020: who's won what?

Victoria Gill, BBC Science Correspondent

The Nobel Prizes for 2020 have been announced: among the winning discoveries, the virus that causes significant liver disease, the gene editing technique called CRISPR, and a supermassive black hole. BBC science correspondent Victoria Gill took Chris Smith through the details, starting with physiology & medicine...

The Nobel Assembly has today decided to award the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly to Harvey J. Alter, Michael Houghton, and Charles M. Rice, for the discovery of the Hepatitis C virus.

Chris - So Vic, what did these men do? What have they actually discovered?

Victoria - It is this beautiful stepwise series of discoveries of, well, hepatitis - the discovery of Hepatitis C - and also how to detect it, that's led to blood tests, that's led to treatments and cures, and the possibility that this potentially lethal virus could be wiped out. There's three types of hepatitis and Hepatitis C, up until the seventies, was unknown; but it was found that patients who had blood transfusions were getting this unknown cause of hepatitis. So Alter and his colleagues showed that blood from these hepatitis infected patients could transmit the disease to chimpanzees; he showed this disease-causing agent in infected people's blood. Then Houghton took that a step further by painstakingly isolating and collecting DNA fragments from these infected chimpanzees, so he found the code of the virus; and then Rice took it even further to show that it was actually this virus, alone, by itself, that could cause hepatitis - inflammation of the liver - which can kill you. So it's this lovely step by step from the seventies to the nineties that has got us from this unknown cause of lethal liver inflammation, to a point where we know exactly what's causing it, that that is the sole cause, and now we have a way of potentially wiping out this virus. We can certainly test for it very rapidly, treat it, and cure it.

Chris - Did you foresee Hep C making a Nobel this year Theo?

Theo - I wish I could say so, but I did read a prediction of it, because I believe the scientists involved had received some of what are seen as the precursor prizes. So they were certainly on the slate.

Chris - It's an important problem though, isn't it? The anticipated burden of disease caused by Hep C: 170 million people around the world, and it's a direct cause of liver cancer and liver disease. So it's pretty important as a pathogen, and the fact we've now identified it and can eradicate it, even; that I think is a prize well-earned, isn't it?

Theo - Absolutely. And it sort of bears comparison, when we're all rather obsessed with one particular virus at the moment: how long it used to take to identify the virus causing a particular problem, and then prove that that virus was the cause. And we have all taken for granted the fact that a new virus has emerged in China late last year, we can already identify it, know that it's causing disease with great certainty, and we will hope that we can vaccinate against it pretty soon.

Chris - Lee, there's some suggestion - I mean, it's a number of years old now, this suggestion - but when you compare the genetic makeup of Hep C and the genetic makeup of a certain group of viruses that infect dogs, some people have suggested that in fact dogs gave us Hepatitis C, and it would have been the very close sort of proximity between us domesticating dogs and those dog owners initially that perhaps enabled that jump to happen. And a bit of a striking parallel - Theo's talking about the fact that we've identified COVID in record time - but the fact that we could actually have a virus that's jumped out of bats and into people to cause COVID, and we've got a virus that jumped out of dogs and into people to cause Hepatitis C. What do you think about that?

Lee - As science has progressed so incredibly, particularly over the last decade, we're going to be able to test that question. And we're not far from being able to do that. We have from the archaeological record, and some genetic record, that we've domesticated dogs inside of the last 30,000 years. And as we begin to get ancient DNA, we should be able to clock that and test the idea: which came first, the Hepatitis C or dog domestication?

Chris - Well let's move on to the Nobel Prize for Physics, which has also come out this week...

One half to Roger Penrose, for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity' and the other half jointly to Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel, for the discovery of the supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy.

Chris - That's one way of putting it, isn't it: the 'supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy'. There was actually a lovely quote, Vic, from Christopher Berry who's a physicist at Northwestern University, and it resonated with me, because he said, "black holes capture anything that gets too close to them. This is equally true about our fascination. Once you start learning about black holes, there can be no escape." So watch out, if you report on them too much you might get sucked in.

Victoria - That's really nice. I think my favourite response to the physics Nobel came from another physicist, Paul Coxon at the University of Cambridge, who tweeted that "awarding the physics Nobel for a supermassive chasm of infinite darkness is very 2020" which I thought really hit the nail on the head. This was a fascinating one. It's a wonderful British scientist, 89 years old, Roger Penrose, who gets half this prize; and then the other half is shared between Reinhart Genzel and Andrea Ghez, who is only the fourth woman to win a physics Nobel. So it sort of encapsulates a lot of the intrinsic problematic issues with the Nobels, and this ongoing issue with the perpetuation of the problematic academic hierarchical system that the Nobels is kind of famous for. But it's also just this real celebration of absolutely fundamental science. What Roger Penrose did is sort of... I mean to me, him applying general relativity to come up with entirely new calculations, the fact that a black hole can be a real thing can actually form in the universe, is kind of another level of thinking for me.

Chris - Well, let's move straight on to chemistry because that was the third and final prize that was announced this week...

Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, for the development of a method for genome editing.

Chris - This is of course the technique otherwise known as CRISPR. Did you see that one coming Theo?

Theo - I think this one looked very likely at some point, because the CRISPR-Cas9 technique has so revolutionised the way that researchers can edit DNA, including the fact that we believe that someone actually used it illegally and ethically to edit the DNA in unborn children. But it's clearly something that has changed the whole way that molecular biology is done. And in contrast to that Hepatitis C work from the 1970s to the 1990s, and which by the way went to three men, this prize has gone to two women for work done in the past decade; and that's exciting on both counts, I think. By studying basic biology they've come up with a tool that has changed basic science already, and it's likely to change medicine as well.

Chris - Vic, how does CRISPR actually work? What does it involve? What will it enable us to do?

Victoria - It's actually the ancient immune system of a bacteria which essentially has this component called tracrRNA, which cleaves, it snips out, a bit of DNA from whatever is attacking it. It basically kills whatever attacking it; its immune system has this pair of genetic scissors. And what these two amazing scientists have done - and they collaborated together to bring together their genetic knowledge and their molecular biology, this is the real kind of chemistry of life stuff - they got together to figure out how to simplify that bacterial immune system, this cleavage, into a pair of much simpler molecular genetic scissors that can be used anywhere. Essentially you can, just as if you were editing a piece of tape and you can snip out a bit and then stick it back together, you can do that with a genetic code. So you can just imagine... actually the Swedish Academy themselves said that it's only imagination that holds back the limitations of what we could do with this technology. I think another important postscript to that is that our morals and ethics is also going to play a big role in terms of what humans will do with this technology, because the possibilities molecularly are boundless.

22:59 - The future of education

The future of education

Jim Gazzard, Institute for Continuing Education (ICE), University of Cambridge

Thanks to the pandemic, we’re entering a world that’s more online; and, thanks to what many are calling the ‘fourth industrial revolution’, it’s a world that’s much more automated and data-driven. Jim Gazzard, director of the Institute for Continuing Education at the University of Cambridge, has been on the front line of having to respond. Chris Smith asked him, firstly, whether young people in the UK should have been sent off to university...

Jim - I think it's a very finely balanced decision. You mentioned young people, and I think that's key. These are people who are needing to get on with their life, needing to get on with their education, and they're relatively low risk; so returning to halls of residence, returning to small group teaching, I think is probably on balance the most sensible decision. But I'm interested in adult education; of course it's a little bit different perhaps for people who are in their forties or fifties or sixties, or students with health conditions, so we decided to deliver all of our continuing education, certainly for undergraduate courses, fully online this year.

Chris - How has, though, the response to learning worked out? Because some people have been saying to me that they go home at the end of the day and they're a bit Zoomed out, square-eyed from staring at screens all day.

Jim - Exactly that. If they've been on Teams all day, or Zoom, then it is quite difficult. So we're trying to break up the learning into smaller chunks and to engage in different ways. What we are hearing from students, particularly because of the global recession that goes along with a pandemic, is that there's a real necessity about learning; whether that's about an enforced career change, whether it's actually a concern about whether skills and knowledge are contemporary. So we've seen a real growth in enrollments - we're over 50% up year on year - and I think this is being mirrored globally. I think sometimes it's for positive reasons, because people have used lockdown to really think about what they want to do with their futures. But as mentioned, it's also for some of these more challenging reasons.

Chris - Lee what's been the experience at Wits in Joburg?

Lee - The teaching has been very good, but we have in the developing world a different challenge: that our students can't afford the bandwidth in the way that the developed world can. Wifi, internet, is not as freely available. So all of our teaching tends to be recorded in advance and we limit the interaction, and I think that's a really sad thing, because like many of you I miss that one on one interaction; it's the things that happen during the course of a lecture, as you follow the students and they challenge you, that is the point of higher education.

Chris - You were quite early to this party though, because when you started making the stupendous discoveries that you have in South Africa, rather than squirrel these findings away in a lab and work on them in isolation for the rest of your career, you actually said, "no, I'm going to scan them, and I'm going to put all this data on the internet so people can download and 3D print their own Homo naledi or Australopithecus sediba," and people are!

Lee - That was just trying to move some of the fighting in this field of palaeoanthropology by showing the evidence, making the evidence available. We were also there very early in going live with the science, experimenting with "how do you go live? How do you communicate science in an authentic way, that also doesn't lose the trust in science, because we make mistakes along the way?"

Chris - Here is the UK's chancellor Rishi Sunak; let's hear what he had to say earlier this week...

Our economy is now likely to undergo a more permanent adjustment. We need to create new opportunities and allow the economy to move forward. And that means supporting people to be in viable jobs which provide genuine security.

Chris - I suppose, Jim, that those sorts of statements are both an opportunity and also a curse for someone in your position, because some things that you may have been anticipating training people for may not actually exist as viable jobs, in Rishi Sunak's words; but there may now be new opportunities, new things potentially, that people want training in, which someone delivering online and adult education... it's an opportunity there.

Jim - Yeah, I think you're right, Chris, there are opportunities and threats. If we want to be serious about science and technology, not only do we need to continue training PhD level scientists, but we need to think about technician level science support. So I think there's going to be some very exciting opportunities in those areas in life science, in physical science, and looking at data analytics, looking at coding. But yes, I think there's going to be creative destruction that's being accelerated around COVID. And we're seeing so-called white collar jobs, that would be exciting professional opportunities even only 10 or 15 years ago, that technology is overtaking with algorithms and machine learning. As an educationalist interested in life wide and lifelong learning it is a really interesting time, but I understand it's a really scary time as well, when I think the norms of employment within an economy in the UK, for example: they're going to change very rapidly, and we have to be ready to respond to that as universities, and education and training providers.

Chris - What's your view on this Theo?

Theo - As has just been said, it's going to be so interesting to see how computers get better at doing the menial things that we do, ranging from driving a car to assessing an X-ray; and how are we going to train people to work around the changing world of work, particularly unfortunately when we face a global economic crisis brought on by COVID.

Chris - It's interesting that both you and Jim just before you brought up computers and coding, because that also made headlines this week, didn't it unfortunately...

Public Health England have admitted tonight that nearly 16,000 cases of coronavirus between the 25th of September and the 2nd of October were not included in daily figures for that period and not transferred to the contact tracing system...

Chris - I think one word springs to mind Jim: whoops. How did that happen?

Jim - That is a really interesting point. I mean, if we are to believe what we've been told, this was about an Excel spreadsheet that hadn't been transferred into the main data repository. Obviously I don't know how it happened, but I would bring this back to skills and training. We need people who have digital skills and we need to be able to design systems that work properly.

Chris - And just very briefly, with your eye on your crystal ball - which I'm sure you have there in your office - what do you foresee as where we will be, from a university point of view, as the university sector, in a year's time? Do you think that organisations like the one that you're running will be at the forefront and it's going to very much be online, or do you think we'll solve this COVID problem and it will be bums on seats back in lecture theatres? Are these changes here to stay?

Jim - Yeah, I think this is going to change universities profoundly. I think there's been probably 20 or 30 years in the UK and Western economies where we perhaps, I don't know, lost our way a little bit. I think we've got to redefine what universities are for. We need to train the next generation of technicians, as I've mentioned; and really thinking about the fourth industrial revolution, what new jobs, what new roles, will be created. Perhaps half of the jobs that will be around in 10 years don't currently exist right now. So what we have to think about in universities is critical thinking and synthesis of ideas, and creativity, and working with new ideas in different ways; and I think that means we perhaps have to get out of discipline silos and think interdisciplinary learning. So I hope universities will view this as a real opportunity - I genuinely think it is - but I think we've got to think about learning as a life wide activity. The skills that we learn at university, if you're 18 or 19... the half life of those skills now might be three or four years, so you're going to have to learn again in your mid twenties, your early thirties, your forties; you might have to change career in your fifties or sixties; and we might have to carry on working until we're 70, 75, or 80. So I think we've got to recondition our learning and the way that we think about learning to respond to how society and technology is changing.

32:60 - A Series of Fortunate Events

A Series of Fortunate Events

Sean Carroll

A new book by evolutionary biologist Sean Carroll, called A Series of Fortunate Events, takes a look at the whole train of unlikely coincidences in our history that led to all of us being here today. Sean joined Chris Smith...

Sean - Well, it's a series of cosmological, geological and biological accidents that really explain both collectively how we all got here, and individually. Some of these events are as great as the asteroid impact 66 million years ago, without which probably mammals would still be an obscure group of animals on the planet, and we certainly wouldn't be having this conversation; right down to the sorting of chromosomes - if I may say - in our parents' gonads, and the unique genetic combinations that come from that. We're each a one in 70 trillion event with respect to our parents.

Chris - Okay, well let's wind the clock back then. We are here today - and we also have with us Lee Berger, palaeoanthropologist, who can also help us out with some of the human evolution - but we've been here for really what's the blink of an eye. So where do we, as anatomically modern humans, stop, and where does the chain of events that actually make it possible for animals that turn into us kick in? Can you just give us some sort of timeline on what these events are and how they fit into our evolutionary history?

Sean - Sure. I start with the asteroid impact - which I think most people have heard of - 66 million years ago, because the more we understand about life before and after the impact, in fact from the fossil record, the more we appreciate that had this event not happened, the fate of mammals is very unclear. Mammals had been around for probably a hundred million years at that time, but life on land was dominated by the great dinosaurs. After the dinosaurs were wiped out because of the ecological catastrophe that that asteroid triggered, mammals that were small really took off. And in fact, only last year there was a treasure trove of fossils unearthed in Colorado here in North America, to really show how rapidly mammals took off once dinosaurs were out of the picture. And eventually those mammals branch into the modern forms we know, and all the different groups including primates.

So we understand without that cosmological event, a six mile wide space rock that was probably circling the solar system for 4 billion years... without that accident, we're not having this conversation. And the margins of that accident are fascinating. It's one thing to say, "we're all here by accident". It's kind of glib, but when you get to the specificity of these events, I think that's where some of the power comes from. And that asteroid: had it for example entered the Earth's atmosphere maybe 30 minutes sooner and landed in the Atlantic, or 30 minutes later and landed in the Pacific, it probably wouldn't trigger a mass extinction. Where it hit matters. And so you're looking at a one in 500 million year event in terms of an asteroid of that size, and it just happened to hit a piece of the Earth that could trigger a reset of life on Earth.

Chris - What about things that have come since then? Because we know that the Earth's climate has been a very changeable thing; over tens of thousands to millions of years it's changed a lot, hasn't it? We've had ice ages, we've had warm periods, we've had the Earth having the poles completely melted at certain points in our evolutionary and geological history. So how does that overlay on this?

Sean - Great point. I want to tee this up to Lee as well. The last 2 million years, we've been in one of the most volatile cycles of the last 300 million. The ice ages, the onset of which was a couple of million years ago... this is an incredibly volatile cycle where you not only have ice sheets advancing and retreating, but really in places like East Africa, it's not so much about temperature as it is about wet/dry. And from the palaeontological record we understand that our ancestors lived through - speaking a little bit longer term, over the centuries or millennia - incredibly dynamic climatic cycles. And it's a widespread view that our large brains are really the result of selection for our ability to craft our own habitats. The ice age has had a lot to do with the pace and direction of human evolution.

Chris - Lee?

Lee - It's so funny, because we keep running into our understanding from ancient DNA, and how we're having to recraft everything we know. And I think it's very exciting to think of these chance events; and they also include now the idea that what was a simple story of human evolution ten years ago... we had a very pat idea of how we actually evolved in almost a ladder like phenomenon. Maybe it was a tree, but it wasn't a very bushy tree. Now, a tree isn't even a good model. We're looking at hybridisation. We're seeing that at any one moment in the past, that we have all of these different species, and really different species, like Homo naledi, Neanderthals, the hobbits, and large brained Homo sapiens all existing at the same time. And it may be just chance encounters that are occurring at any moment between two of these that allows a hybridisation event. Ten years ago we thought Homo sapiens was just this purebred race horse out of Africa, and we were destined to dominate this world because of our large brains. Now we know we're this mongrel, full of all kinds of other DNA, and messed up; and likely almost all of that was chance, through chance meeting of species. Some of it driven by climate, some of it driven by catastrophe, and some of it just in our genes.

38:29 - Some COVID risk genes come from Neanderthals

Some COVID risk genes come from Neanderthals

Lee Berger, University of the Witwatersrand; Sean Carroll; Theo Bloom, BMJ

A cluster of genes that is linked to more severe cases of COVID-19 appears to have originally come to us from Neanderthals, according to a report in Nature. Chris Smith asked Sean Carroll, Theo Bloom, and Lee Berger to unpack the story...

Lee - So Neanderthals are both a lot like us, and a lot different from us. They're more robustly built, they're shorter, they're stockier; and they were considered an absolutely separate species. In fact, scientists used to get in bone fights over whether or not we wouldn't run away from each other, and they'd ever even met. And then ancient DNA came along, and that plays into this story because we mapped out the Neanderthal genome, and suddenly we found out that most humans - including many Africans - had some levels of Neanderthal DNA, something between 1% and 5% within us. And that's where this story comes in.

Chris - And Sean, would you judge that in the book as a fortunate event - the interbreeding of us with Neanderthals - or not? When it comes to coronavirus, it sounds like it might not be...

Sean - Might not be. No one can tell the future; and so really natural selection only operates in the present. So probably the reason why this block of DNA is in a significant number of humans is that there was some positive selection for it, but now here's this new pathogen and it's a disadvantage. And that's a very common story about human genetics. We know, for example, that there's a very rare variant that makes people impervious to HIV. The HIV virus is perhaps a century old, but this variant we can find in bronze age bodies buried in Europe. So these genetic variants have been around for a long time, and perhaps they were favoured by certain other pathogens; they may have conveyed resistance to other pathogens, but now they're either advantageous or disadvantageous to new ones that come along now.

Chris - Theo, what's your reading of Sean's fortunate events? He made reference to our parents gonads, and he's getting at basically the rearrangements of genes in there that render us unique on Earth - unless we have a twin or we've cloned ourselves.

Theo - Yeah. So this notion that, although we're initially taught that genes all behave independently, actually they're inherited in blocks along chromosomes that are inherited together simply by proximity. And this example of the piece of Neanderthal DNA that seems to have an effect on COVID resistance: who knows what genes it may carry, or why it was selected for at some point during evolution. At this point we don't know; we just know that there's a linked box of DNA that's come to us from our Neanderthal ancestors, and it seems to be differently distributed among different groups on Earth at the moment, and may even underlie some of the differences in susceptibility to COVID. But really we're very early in understanding that story, I would say.

Chris - Do we have any idea why those Neanderthals had those genes, and what they did for them?

Sean - The first answer to that is a flat out no, we have no idea. And the second answer to that is a lot more complex. No, they didn't have to have an advantage. They might've just been there and we might just carry them. We need to be cautious about direct attribution, particularly in the middle of a pandemic, because as Theo would absolutely know - I'm sure you were inundated with these ideas - we don't know this right now. It will have to prove the test of time. Don't think that if you carry Neanderthal DNA that you're at some higher risk of this, or if you don't, you're at lesser risk; keep wearing your mask, keep social distancing. Those are the things that work until we get a vaccine.

Chris - And Sean Carroll, the author of A Series of Fortunate Events, I suppose it was another fortunate event that you were able to come on our program today! So thank you for joining us and thanks for telling us about the book. What do you think the next most fortunate event is going to be? A vaccine?

Sean - Yeah, well, that's not fortunate. That's just science, and scientists working very hard. And I have a little inside insight to that through a documentary film that we're making; and there are people whose names you don't know who've been working tirelessly around the clock, in an unprecedented challenge to develop this vaccine. So I think that's a nice side effect of our big brains, is the practice of biomedical science. So hopefully that'll get us all in person in 2021.

43:23 - Attenborough's new film: A Life On Our Planet

Attenborough's new film: A Life On Our Planet

Colin Butfield, WWF

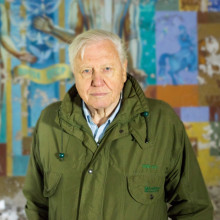

David Attenborough calls his new film, A Life On Our Planet, "my witness statement and my vision of the future - the story of how we came to make this, our greatest mistake; and how, if we act now, we can yet put it right." Chris Smith was joined by the films executive producer, WWF conservationist Colin Butfield...

Colin - When making the film we realised very, very early on that David has had this extraordinary life. Because of the time he was born and the job he had, we figured that he's probably seen more of the natural world than any other human being who has ever lived or will ever live; because before him there was obviously no air travel, and now so much of the natural world has been lost. The unique life he's had means he's seen something that nobody else has seen, and in the process of doing so, of course, he's witnessed this enormous scale of change on our planet; probably a bigger change to the natural world than any other time in the last 10,000 years. So he has a unique witness, a unique perspective, as a result of that. And that was a very appealing storytelling lens because I think when we talk about these massive global changes, it's quite hard for people to understand, to grasp. It feels huge. Putting it in the context of one human's lifetime makes that somehow easier to understand.

Chris - What will the viewer actually see? How have you done this? Because obviously, Sir David is now in his 10th decade, he can't travel in the way that he once did. So how have you managed to capture the spirit of an Attenborough doco, and do it in a way that brings people the action and has very much his fingerprint on it?

Colin - Well it's interesting! Even though you're quite right, David is 94 - he was 92, 93, when we were making this - he still did travel out to Kenya, to Maasai Mara, somewhere he had been to many times in the past, to show what's changed; and also out to Chernobyl, which obviously is a very different landscape and environment for him. But we start and end the film in Chernobyl and show the change that's happened there, from obviously the human civilisation effectively being evacuated and left destroyed, to nature reclaiming the territory. And we intersperse those location shots with some archive going back to his famous sequences in his career, and also footage from today that shows some of those changes. Some examples being: he's one of the first people to film and present from coral reefs, and then we've shown the modern footage of the same coral reefs bleaching. We've got footage of him in Borneo 40 years ago finding orangutans, and then footage of Borneo today and showing what's changed there. So you get that juxtaposition of what he saw then and what he saw now; but also of course, being David Attenborough, obviously his great expertise is in the natural world, so when describing even changes that are very human-centric he often uses examples of nature to illustrate that. One example would be that when talking about the impact of meat consumption on the natural world, he chose to explain it from the Serengeti and explain in the context of the ratio of predator to prey animals, and how much space prey animals need. There's a hundred prey animals on the Serengeti for every predator. And therefore the space that's needed effectively to produce meat protein, and using that to illustrate the changes that are happening in the human world. So we're able to have the gorgeous wildlife sequences and place lots of them in a very human context.

Chris - There is this phenomenon dubbed the "Attenborough effect": when David Attenborough highlights something, it usually galvanises attention and hopefully also translates into action. The best example being plastics, for example. Are there any things that you have purposefully picked for this one which you're thinking, "we want to provoke people, we want to highlight very important issues, or make people change"? Because it was obvious with the plastic doco that if you show that cause and effect, you immediately show people what they need to do to try to help. Have you done anything similar with this one?

Colin - Yeah. The two things we really, really wanted to get across in this were probably the biggest tipping point issues facing our planet; the biggest places where things will go into free fall, the changes are happening so fast. Those two examples are: the change in the Arctic sea ice and how fast the world's warming, very visually showing the change that's happened during David's filming career, actually not even just his lifetime; going to visit locations where you would expect to be surrounded by ice, and obviously the wildlife that is on the ice and uses the ice for hunting, and the ice not being there. And the second one was tropical forests; in particular, how fast tropical forests have been declining shows that the Amazon in particular, as an example, is approaching a tipping point where the amount of rain that's needed to self-sustain that that rainforest is being lost through lack of rainfall, and also deforestation and fires. And it faces a moment where it might tip into a dry savannah. And then placing those issues back to ourselves, in particular highlighting levels of meat consumption and investment in things like fossil fuels. Although each of those things are a bit more complex than purely a plastic bottle or a plastic carrier bag, which has obviously had a big effect because it's extremely tangible what each one of us can do and what that impact is, I think here we wanted to get a sense of the whole scale of the destabilisation of our planet and what we need to do to stabilise it again. And that's a bigger, more complex thing, but I hope and feel - and certainly the reaction in the first few days seems to suggest - we've got something across.

Chris - Lee, you've made quite a few films, in your case with National Geographic, about your work. It really does work to galvanise attention around an issue, doesn't it? I mean, have you found that interest in paleoanthropology, interest in our human story and therefore people's sort of sense of guardianship of the planet, has improved through what you've done making telly programs that bring the science to people?

Lee - Oh it absolutely does. There's probably no more effective way to reach millions and millions of people with messaging. But just to follow on what was being talked about that Sir David's done here: we're living in a world that's seen the cost of 8 billion human beings. COVID, the destruction of natural habitats, the cost to all other living things. And we need messages like this now, because this is going to be the new norm. It isn't going to be waiting around for viruses when we reach 9 billion and 10 billion and 12 billion consuming humans; we have to make choices, and we have to do it right now.

Chris - Theo?

Theo - Yes, I find this particularly poignant because I was a teenager when David Attenborough's Life on Earth came out, and it was the thing, when I was asked at university interviews "what made you want to study science?" that was my answer. I think he changes a lot of people's lives, and he's really determined now, even in this 10th decade, to keep changing our attitudes to the natural world. And it's really very inspiring.

Chris - And Colin, are you able to sort of capitalise on the program in other ways beyond just sort of making a program and educating people, are there other ways in which you can then take the momentum that's created and then build on that to get more change or to get more activity off the back of it?

Colin - Yes, I think there is. One of the things that's happened already in only a couple of days since we've released it is various big companies, as well as members of the government, getting in touch with us and asking us to host screenings and to share it with employees or with politicians. And I think you find, and hopefully we're going to find with this one, but you certainly find with documentaries, that it can be an interesting moment to provoke a conversation within companies and governments where change can be made. So it ‘lightning rods’ an issue that perhaps many people have been talking about for quite some time, and gives a focal point, a moment where it feels we must respond to this. And that's a sort of sense that we're getting at the moment. It's early days, but it feels like there's a moment where employees are asking their bosses, "what we can do about this, surely we've got to address these issues". And it's not just from one documentary, but it's from a building of this drumbeat over time. And then a documentary like this, particularly if fronted by David, tends to have a flashpoint that draws a lot of attention and forces people to make a statement one way or the other towards it.

Chris - And Lee, is there anything we can learn from what happened to our ancestors that might help to focus minds today? We think that obviously every experience we're having is unique. Is there evidence that actually our ancestors went through times when the planet was under stress, obviously not of their making like the present situation is in our case, but the outcome could nevertheless be the same?

Lee - I think that the thing that humans should take away from the idea of studying the human historic past is that we should lose our arrogance. Extinction is the norm. There have been dozens and dozens of our closest relatives with brains like ours, with adaptations like ours, that have existed through the last millions of years, and they are all gone. And we can go that way too.

Chris - Theo, any passing thoughts from you? It's a pretty poignant and sobering note from Lee to finish on.

Theo - I'm more of an optimist, and I hope that the human ingenuity that has got us into this terrible pickle will help get us out again.

Comments

Add a comment