Tackling Drug Resistant Tuberculosis

Interview with

Chris - We've been hearing a lot about new infections, but sometimes old enemies come back to haunt us. Tuberculosis, TB, is a disease which many of us think of as a thing of the past, but now, it's back on the rise in the UK and elsewhere in the western world. Part of that might be down to the recent discovery that TB can conceal itself in cells in our bone marrow, even in people who've ostensibly been cured of the infection.

Chris - We've been hearing a lot about new infections, but sometimes old enemies come back to haunt us. Tuberculosis, TB, is a disease which many of us think of as a thing of the past, but now, it's back on the rise in the UK and elsewhere in the western world. Part of that might be down to the recent discovery that TB can conceal itself in cells in our bone marrow, even in people who've ostensibly been cured of the infection.

We'll hear more about that in just a minute from Stanford physician Dean Felsher, but first, consultant microbiologist Sani Aliyu is with us to talk about other emerging threat from TB which is that the bug is rapidly becoming resistant to the majority of the antibiotics that we use to treat it. So, Sani first of all, what actually is TB and why is it such a problem?

Sani - So, TB refers to tuberculosis. It's been with us for quite a while. It's an infection caused by a bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It usually manifests with cough, respiratory symptoms, fever, night sweats and could affect any organ in the body really but mostly, the lungs.

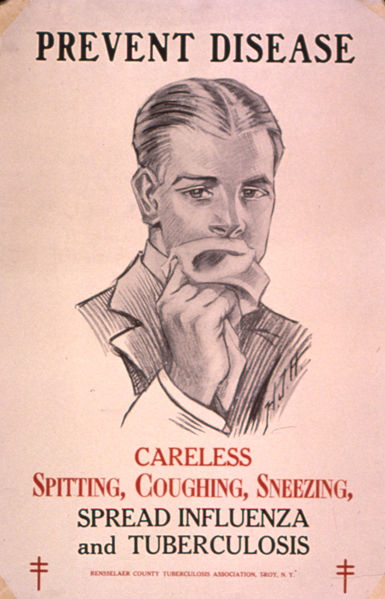

Chris - How do people catch it in the first place?

Sani - Transmission is usually called airborne, simply because when you cough or when you sneeze, or you talk, you have droplets that contain the bacteria. And the droplets can survive in the environment for prolonged periods of time. They tend to be suspended and if you inhale the droplets, the bacteria goes into your lungs and then you get infection. By inhaling the bacteria, you don't necessarily get active disease. You can get latent disease because it's estimated worldwide that 1 in 3 people are infected with TB, so it's very common.

Chris - When you say latent disease, what is actually going on? So, you've been infected but you don't have TB actively growing in you. Is that what you're saying?

Sani - That's right. So, you've been infected with the bacterium that's sitting dormant or latent in your body cells and it's hidden. It may not necessarily come up and cause symptoms. It's only when you have symptoms, that you have tuberculosis disease. The most cases of active TB arise from the latent form where you have the bacteria replicating and then it causes symptoms, usually, in relation to immunosuppression or old age.

Chris - What does it do in the body? Does it just cause chest disease problems or does it go elsewhere too?

Sani - TB can affect virtually any organ in the body. Severe tuberculosis for instance can affect the brain, can affect the meninges, so it can have meningitis. It can affect the bones. In the past, what we call Pott's disease where you have people with infection involving the spine, has been well-described. You can also have genitourinary tuberculosis, abdominal TB.

Chris - Now, when people talk about drug-resistant TB, first of all, how do you actually treat normal TB? What's the regimen?

Sani - The first drug that was produced and that was found to be quite effective for TB was streptomycin in 1944 and since the '60s where rifampicin came in, TB has been treated with a cocktail of at least 4 drugs. They're called first line drugs. So here in the UK for instance, we have rifampicin and isoniazid which are considered the core and most powerful anti-TB drugs available. Then you have pyrazinamide and ethambutol. You could also have injectables.

Chris - And you give those for quite a long period of time don't you?

Sani - That's right. For pulmonary disease, you give the cocktail of drugs for a total of 6 months.

Chris - And what's the reason why TB is now no longer responding reliably to that cocktail of drugs?

Sani - So, a combination of factors really. What's been happening for the last 20 years is we have a large cohort of people especially in the middle and low income countries where you have TB that's not really being treated properly. You have both misuse and mismanagement of the drugs. If you have patients with tuberculosis taking the drugs in a way that they're not supposed to, either taking one pill or taking an inadequate dose, or taking for a very short period of time, you tend to develop that resistance simply because you have that drug pressure which pushes the bacteria to develop mutations.

Chris - And so, what is the status of TB response to our medication now? How many cases of TB would we regard as resistant?

Sani - So, worldwide, we have what we call multi-drug resistant TB which essentially is resistance against the two core drugs rifampicin and isoniazid. It's estimated by the WHO that there are probably about 65,000 cases of multi-drug resistant TB, mostly in high incidence countries such as Sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent and central Europe.

Chris - And what about the more resistant form, the XDR-TB that we're now beginning to hear about extensively drug-resistant TB? How does that differ?

Sani - So, extensively drug-resistant TB is really a progression of MDR-TB. In other words, in addition to resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid, you also have resistance to a class of antibiotics called the quinolones and to at least one injectable antibiotic. And what this confers is really a difficulty in managing the TB. You have to give a cocktail of drugs that are usually second or third line drugs that aren't as effective as the first line drugs. You have to give them for a longer period of time, they're much more toxic, they're more expensive and it's a nightmare really.

Chris - And how common is that form of TB?

Sani - Fortunately, in the UK, pretty rare. In 2011, this is based on information from the Public Health England website, more recently called the HPA, there are about 81 cases of multidrug-resistant TB up to the end of 2011, but only about 24 cases of XDR-TB in total, of which 6 were confirmed in 2011. So, it's a pretty rare disease fortunately in the UK.

Chris - But it's not 0 is it, which means we need to keep an eye on that. Thank you, Sani.

And Dean Felsher, now you've recently shown that TB can hide away inside the body and remain in a viable state even in people who have been what we would regard as cured.

Dean - Right. So, what we found was that tuberculosis can hide in a very unexpected site. It can hide in a rare population of bone marrow stem cells that have the special name, the mesenchymal stem cells. And they have multiple biologic properties that make them a perfect place for tuberculosis to hide away. They like to migrate around the body. They're naturally drug-resistant. They're naturally resistant to the immune system. They can tolerate living in a low-oxygen state which is typical of places where tuberculosis infects. So, in many ways, they represent a sort of perfect host cell. It's been known for a long time that tuberculosis can hide in other normal cells in the human body, but this population of bone marrow stem cells is rather surprising finding that we reported recently.

Chris - How did you discover that TB was lurking in those cells?

Dean - So, our work has very much been interested in the role of stem cell and stem cell kind of biology in disease processes and there was a very creative idea that tuberculosis maybe taking advantage of a normal stem cell population. And I decided to pursue this by studying whether or not tuberculosis could live in normal human stem cells and we were able to show that indeed they could preferentially infect and become dormant in these normal human stem cells and then we're even able to show evidence that this was true in human patients.

Chris - Now first of all, talk us through how you think TB gets to those stem cells in someone who gets infected via the lung or breathes in some TB, and then what happens to the TB once it's in the stem cell?

Dean - It's known that tuberculosis will form a structure that we call a tuberculosis granuloma and other scientists had reported that some of the body's stem cells like to migrate to the granuloma. And what we think happened is, that these special type of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells are attracted to the site of infection and that tuberculosis has figured out a way to get into these cells and then use them as a way to escape the normal sorts of mechanisms that the host immune system is trying to use to get rid of the tuberculosis.

Chris - So, those cells get infected in that site in the lung and then they go back to the bone marrow, do they?

Dean - They can go back to the bone marrow because they're capable to migrate as well as go to other sites.

Chris - And how did you know that once the TB is in those cells that it's actually viable and that it remains in a viable state so it can come back to life from within those cells later?

Dean - Yeah, we were able to take from patients who have been treated extensively in a way that you would expect they were cured of tuberculosis, people we knew had tuberculosis, take their bone marrow out using a special procedure that we use as haematologists called a bone marrow biopsy and purify this subpopulation of bone marrow stem cells and show that we cannot only detect the DNA of tuberculosis, but we could actually recover viable tuberculosis using microbiological assays in the laboratory.

Chris - So, these are people who've had drugs that have cleared them of signs of being infected with TB, they would be regarded as cured, but actually, you can get stem cells out of their bone marrow and there's a viable TB living in there?

Dean - Exactly.

Chris - So, what are the implications of that?

Dean - Well, the implication is that it may be that if we can figure out a way to get rid of tuberculosis from these bone marrow stem cells, we might be able to come up with a better long term treatment for tuberculosis.

Chris - Let's hope so. Sani says, with one person in three carrying it, we need to move fast, don't we? Thank you very much to Dean Felsher from Stanford School of Medicine and also before him, Dr. Sani Aliyu who is from Addenbrooke's Hospital is Cambridge.

Comments

Add a comment