German scientists have used DNA from ancient skeletons to rebuild the genetic sequence of  mediaeval leprosy.

mediaeval leprosy.

Caused by Mycobacterium leprae, leprosy was at one time a worldwide scourge affecting millions. But for reasons scientists don't understand, the disease abruptly disappeared from Europe during the 16th Century and nowadays is found only in the third world where it causes about 200,000 cases of the disease per year.

Victims are thought to pick up the infection by breathing in airborne droplets laden with the leprosy bacteria which have been coughed out by infected individuals.

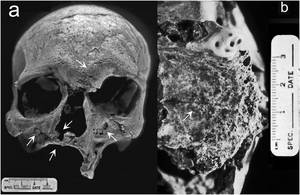

Contrary to folklore, the disease doesn't cause parts of the body to drop off, but it does attack nerves, causing sensory problems, and growth of the bacteria in the skin and nasal passages can cause disfiguring changes to a victim's appearance.

Leprosy also damages the skeleton, leaving characteristic changes in bones, and it was from 5 skeletons bearing these hallmarks that Tubingen University researcher Johannes Krause and his team extracted DNA and successfully decoded the genetic sequences of the leprosy that had ravaged these individuals more than 600 years ago.

Incredibly, the level of bacterial DNA preservation was outstanding, enabling the scientists to assemble a complete genome map for the organism.

The team put this down to the fact that the leprosy mycobacteria have a tough, waxy cell wall, which can act as microscopic time capsule, preserving the DNA inside. But most surprising of all is that when the team matched up the leprosy sequences from their skeletons with the DNA code of modern leprosy strains still circulating, they were almost identical.

This proves that leprosy didn't disappear after the middle ages owing to some dramatic change in the bactierum itself, the researchers argue in their paper in Science.

Instead, they say, some other factor must be responsible, such as the disappearance of another - as yet unknown - pathogen that made people more susceptible to the disease; or perhaps living standards, nutrition or overall health improved, making the population less susceptible and pushing out the bug.

- Previous How aspirin blocks cancers

- Next Gene therapy focused on eyes

Comments

Add a comment