In this NewsFlash, how cancer cells spread to new areas, the discovery that ancient man built anti-insect beds, and ways to reduce your cancer risk. Plus, how a taxi driver's brain change as they acquire "the knowledge" of London's streets and the fishy way to deter unwanted attention...

In this episode

00:24 - Seed and soil – understanding how cancers spread

Seed and soil – understanding how cancers spread

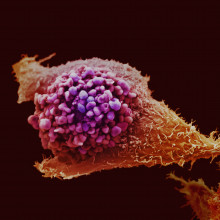

Cancer is a growing problem - and because we're all living longer, we're more likely to develop the disease at some point in our lifetime. Although we've got a lot better at treating the disease in recent years, it does become a lot more tricky once it has spread through the body - a process called metastasis, which is the main cause of 9 out of 10 deaths from cancer.

So there's understandably a lot of interest in understanding why cancer spreads, and how we can stop it, and in a paper in this week's issue of the journal Nature, Ilaria Malanchi and her colleagues have made an important step forward.

Cancer spreads when cancer cells break away from a tumour - the primary tumour - and travel around the bloodstream or lymphatic system, looking for new places to start growing, forming secondary tumours. The researchers were intrigued by the fact that although many cancer cells set off around the body from a primary tumour, only a very small number of them actually form secondary tumours. It's a bit like a dandelion throwing off thousands of tiny seeds, but only a tiny handful of them actually landing somewhere where they can grow.

In this new paper, the researchers have discovered that it's a bit of both. The scientists were studying an animal model of breast cancer that spreads to the lungs, and found that secondary tumours in the lung could only be started by a small group of cancer stem cells - these are the 'immortal' cells thought to be at the heart of many cancers, and make up less than 5 per cent of the cells coming from a tumour. So, there's definitely something special about these cells. But still, not all the available cancer stem cells went on to form secondary tumours, so there must be something special about the places they land too.

The scientists homed in on a protein called periostin, which is produced by supporting cells - known as stromal cells - found in the places where healthy stem cells grow, and also in places where secondary tumours grow. The scientists found periostin in the stromal cells in secondary tumours in the lungs, but when they looked at normal, healthy lung tissue, they didn't see any periostin -and, importantly, they didn't see periostin in the lungs of mice who had breast cancer that hadn't yet started spreading.

When the scientists looked at mice with cancer that had been genetically engineered to lack periostin, they found a massive reduction in the number of secondary tumours, proving that it's extremely important for helping cancers to spread.

The scientists think that the cancer stem cells give out some kind of signal that makes supporting stromal cells produce periostin, which in turn causes the cancer cells to switch on processes that make them settle down and grow. Effectively, the scientists think that the cancer stem cells are wandering around the body, shouting out a message to stromal cells. Some of the stromal cells hear this message and respond, making a suitable environment for the cancer stem cells to bed down and take root.

This early research is very exciting because the processes the team have uncovered could be at the heart of many different types of cancer that spread.

04:06 - Fred Flintstone's bed uncovered

Fred Flintstone's bed uncovered

Writing in this week's Science, University of Witwatersrand palaeontologist Professor Lyn Wadley and her colleagues describe an excavation they have carried out in a cave site called Sibudu in South Africa's KwaZulu Natal Province.

Dating from 77,000 years ago, the team have uncovered successive layers of sedge, and other plant materials including grasses, arranged on the floor of the cave and covering an area between 1 and three metres across. Also within the oldest deposits are thin layers of leaves from the Cryptocarya woodii - also known as the Cape Laurel - tree.

Trees of this species are well known to practitioners of traditional medicine, and chemical analysis of the leaves has confirmed that they contain a range of insecticidal compounds, including alpha-pyrones.

It's likely, therefore, that the ancient middle stone age inhabitants of this shelter were aware of the beneficial mosquito-repelling qualities of these leaves and protected themselves by using them within their bedding.

It's likely, therefore, that the ancient middle stone age inhabitants of this shelter were aware of the beneficial mosquito-repelling qualities of these leaves and protected themselves by using them within their bedding.

Moreover, these early humans were also pioneers of infection control, it seems, because from about 73,000 years ago there's evidence in the cave that, rather than make their beds, the inhabitants regularly burned them. This would have had the effect of helping to rid the environment of parasites and other insect pests.

The finding is extremely important because, whilst there is robust evidence of the activities of stone age peoples out in the field, their domestic arrangements were much less well understood. Maybe they even pre-empted the inability of the teenager to make a bed, which is partly why they torched theirs...

06:46 - Reducing Cancer Risk Factors

Reducing Cancer Risk Factors

The biggest study so far into cancer risk factors confirms our understanding of the lifestyle choices that may lead to cancer...

Kat - For my day job I work for Cancer Research UK and we put out a very big story this week looking at risk factors for cancer. [The paper showed] that around 100,000 cancers a year are caused by just four preventable risk factors: Smoking, drinking too much alcohol, being overweight and not eating enough fruit and veg.

Chris - But that's not rocket science, is it? Because we did know that...

Kat - It's absolutely not. But this is the biggest paper so far to have come out that's looked at lots of different types of cancer and lots of different risk factors, and actually really been able to quantify it. It's the most reliable data we have on the links between a lot of different risk factors, not just the big ones like smoking. Smoking is by far and away the biggest risk factor for cancer, but [this paper looked at] many other ones, things like UV, occupational exposure and all these kinds of things. And we've been able to put some hard and fast numbers onto these, about how much [these avoidable factors] can increase your risk of cancer.

Chris - So, can you just very briefly give us a couple of them and explain why this adds new value and new insight into those areas?

Kat - Well in some ways, it's not surprising to a lot of us who work in cancer but obviously, the really big one is showing that almost a quarter of cancers in men are down to smoking. That's a really, really big risk factor. But interestingly as well, one of the things that came out is that not eating enough fruit and veg is a much bigger risk factor in men than in women. This is because generally, men don't eat enough fruit and veg compared to women. So there were some interesting things that came out, but it was more or less a no-brainer! It's nice to see all the data there in a way that can really be explained and shown to people.

Chris - And if people would like to follow up and see this data, where should they go?

Kat - There's a really nice run down of it and a really good infographic on the

Cancer Research UK Science Update blog, so you can go and have a look at some of the factors there. There's a very interesting discussion going on there because some patients have felt that putting this information out is blaming them for getting cancer and of course, for an individual cancer, it's very difficult to say exactly what caused it. But it's more important that we can tell people we know what can increase your risk and what can reduce your risk as well.

09:00 - Navigating a Taxi Driver's Brain

Navigating a Taxi Driver's Brain

Professor Eleanor Maguire, University College London

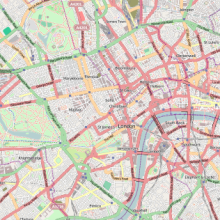

Qualified London taxi drivers know their way around over 25,000 streets in the capital. And, if you scan their brains, you find that the structure called the hippocampus, which contains a mental map of the world around us, is much bigger than it is in the average non-taxi driver. But was it bigger to begin with, or did learning London like the backs of their hands trigger the cabbies brains to change? Now, UCL's Eleanor Maguire thinks she knows...

Eleanor - Animals who do a lot of navigating often have a bigger hippocampus than animals of the same species who don't engage in much navigation. So we wondered if the same would be true of the human brain and whether those who navigated a lot would also have a bigger hippocampus than those who didn't navigate so much. And so, about 11 years ago, I studied this using Magnetic Resonance Imaging on some London taxi drivers and we indeed found that they had greater grey matter volume in part of their hippocampus than people who didn't navigate so much.

Chris - I guess one problem though or one criticism of that is that it's purely observational in the sense that you look at this group, they're taxi drivers. Do they have a very big hippocampus because they're taxi drivers or do they have a job as a taxi driver because they have a very big hippocampus which means they're endowed with the very good map in their head.

Eleanor - Yes and that's a very important point and in fact, that's one of the prime observations of the current study, was to try to see if we could document within specific individuals the change that might occur in the structure of the hippocampus, purely as a consequence of acquiring this very detailed mental map of London.

Chris - So how did you actually do it?

Eleanor - Well what we did was with the cooperation of the Public Carriage Office, we recruited trainees who were just starting there and training as London taxi drivers and we scanned their brains and we tested their memory. And then off they went to try to acquire the knowledge and this takes about 4 years on average, 3 to 4 years. And so, when people had qualified, we invited them back and we scanned their brains again and tested their memories again. And we were able to, in the first instance look at people before they started and see if there was anything in their brain or their behaviour that could predict who would eventually qualify because the interesting thing is only 50% of the trainees actually went on to qualify. It's an extremely tough thing trying to become a taxi driver in London.

Chris - The odds are slightly better in medicine. Did they give you any reason why they dropped out, the ones that did drop out because I mean, there may have been perfectly sound reasons other than cognitive ones?

Eleanor - Absolutely and I think it's difficult to know. It's probably quite a heterogeneous group in the sense that some people probably did find it very tough going and they just didn't have the navigational skills to pursue this, but it's also the case that embarking on this training can be time consuming, can take time away from your family, it's a big financial commitment, and in the current climate undoubtedly, some individuals had to withdraw as a consequence of those sort of issues. So it's not easy to know exactly why people dropped out and sometimes people can say they dropped out for one reason but maybe it was another reason and so on. So it is quite a mixed group, but we did end up with a group that didn't qualify, a group that did qualify and then of course, we had control participants who didn't engage in any training at all but still, we scanned at the start and at the end of the study, just like the trainees.

Chris - Probably, the most important question is, those people who you scanned at baseline and then they became qualified taxi drivers, did you see any differences in their brains?

Eleanor - We did. For those who qualified, we found that between the start and the finish of the study, the back part of their hippocampus had increased in volume and no other part of the brain had changed, just very specifically this back part of the hippocampus which is what we found in our previous sort of observational studies where we compared taxi drivers to non-taxi drivers. So it was fully in line with our previous results.

Chris - And the controls, they didn't show any changes?

Eleanor - No, the controls and those who didn't qualify, their brains remained exactly the same from start to the finish of the study.

Chris - Now what about other measures of cognition because you said you also tested their memories in other ways? So rather than just looking at the structure of the brain, you also looked at function. What were the differences then before and after?

Eleanor - Well obviously, the first thing we did was we tested people's general intellectual ability just to make sure that there were no differences in that regard. So the IQs for example of the individuals were all very similar. We then tested their basic knowledge of London in terms of understanding spatial relationships between landmarks in London. And then we did a whole range of other memory tests that looked at their ability to remember verbal material, words or pictures or other types of spatial information. So we did those tests at the start and then we did parallel versions of those tests at the end of the study.

Chris - And how did the results of the before and after compare amongst all the groups?

Eleanor - Well we found that the controls didn't change and we found that the trainees, particularly the qualified trainees became much better in terms of their knowledge of London and the proximity of landmarks to each other which of course you'd expect because they were trying to actually learn that information. But what was most interesting was that on other tests of spatial memory, those who qualified actually performed worse at the end of the study than they did at the start. And this is something we found previously in our studies of taxi drivers that although they are experts in terms of navigating around London, perhaps there's a little bit of a price to pay for that expertise in that they become a little bit worse at dealing with information of other kinds. And that kind of makes sense you know, somethings got to give when you're taking in a lot of information.

Chris - And of course, you're left with another problem which perhaps you'll answer in another 10 years which is, those people that didn't drop out and did show this change, is there something special about them and that their brain is more adaptable, it can incorporate new cells, make more grey matter when they need to do a task like this, compared with people who find it less easy?

Eleanor - Yes, I think that is another important question and so, we must consider the reasons for why people fail to qualify. It may be that there are genetic predispositions to hippocampal plasticity in the individuals who qualified, allowing them to expand their knowledge and so, expand the volume of their posterior, the back part of their hippocampus. And there may be other individual differences that come into play as well. So I think this is a very important issue because what we all want to know is given any individual, what can they hope to achieve? How much can they learn? What capacity does their memory and their hippocampus have? So I think it's going to be very important to understand these individual differences in future studies.

Chris - That's was Eleanor Maguire from the University College London and she published that work this week with her colleague Katherine Woollett in this month's Current Biology.

17:15 - Bed Bugs, Night Shifts and Deterring the Affections of Fish...

Bed Bugs, Night Shifts and Deterring the Affections of Fish...

Coby Schal, North Carolina State Universitys; An Pan, Harvard University; Safi Darden, Exeter University

Bed Bugs from Abroad

The recent resurgence in bed bug infestations taking place in western countries is owing to the biting insects being re-imported from abroad rather than reoccuring locally. North Carolina State University's Coby Schal analysed the genetic diversity of bed bugs collected from outbreaks along route 95 on the US East Coast.

is owing to the biting insects being re-imported from abroad rather than reoccuring locally. North Carolina State University's Coby Schal analysed the genetic diversity of bed bugs collected from outbreaks along route 95 on the US East Coast.

Coby - Because we found this extremely high genetic diversity in populations along the east coast, that should suggest to us that there are multiple introductions of bed bugs coming into the United States for multiple sources and that sort of pattern would argue against local resurgence of bed bugs. It suggests that they're coming from other places. It's difficult to place the blame on any one group, but I think international globalisation and commerce, and increased transport are very likely involved.

Preliminary research on genetic diversity in bedbug populations presented in Philadelphia, at the

annual meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, December, 2011.

---

Increased Risk of Diabetes on the Night Shift

Working rotating night shifts can increase a woman's risk of developing type 2 diabetes by up to 60%. This appears to be at least partly down to night work also causing weight gain. Announcing the results in the current edition of PLoS Medicine, Harvard scientist An Pan looked at data from 170,000 women, aged 25 to 67, who had been followed up for between 18 and 20 years...

An - Compared to women who do not do any rotating shift works, women who have already done 1 to 2 years of shift work has about 5% increased risk. For women who do 3 to 9 years shift of work, the increase rate jumped to about 20% increase risk and they will go higher, more than 20 years of rotating shift work the increase rates go about 60% increase. Body weight explains a lot of associations people who do not shift work gain more weight during the follow up, compared to women who do not do shift works.

Rotating Night Shift Work and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Two Prospective Cohort Studies in Women

---

The Fishy Way to Deter unwanted attention

Non-receptive female fish resort to hanging out with a more attractive counterpart to divert unrequited male mating advances away from themselves. Working with guppies, Exeter biologist Safi Darden found that, given a choice, females for whom the time wasn't right would actively seek out a fitter female for company.

Safi - Now that we knew that females would receive less attention if they were with a more sexually attractive female, did they actually actively make this choice to spend time with a more sexually attractive female to avoid male attention? And when we gave females that weren't receptive to male attention, the choice to swim next to a more attractive female or an equally attractive female, we found that she preferred to swim in close proximity to the more attractive female. When we test that fish that were receptive, they didn't have any such preference. And this has important implications for how these and other fish organise their social hierarchies. It was published this week in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

were with a more sexually attractive female, did they actually actively make this choice to spend time with a more sexually attractive female to avoid male attention? And when we gave females that weren't receptive to male attention, the choice to swim next to a more attractive female or an equally attractive female, we found that she preferred to swim in close proximity to the more attractive female. When we test that fish that were receptive, they didn't have any such preference. And this has important implications for how these and other fish organise their social hierarchies. It was published this week in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Social preferences based on sexual attractiveness: a female strategy to reduce male sexual attention

Related Content

- Previous Do fish orgasm?

- Next Monitoring Moods with Mobiles

Comments

Add a comment