Small balls of brain tissue grown using stem cells from patients with autism are helping to shed light on what causes this and related disorders, according to a new study from the US.

new study from the US.

About one baby in every one hundred will develop autism. The symptoms include difficulty in communication and relating to others, and behavioural problems.

A number of genes have been linked to the trait, but they each individually account for only a few per cent of cases, suggesting that they must lie upstream of a more fundamental developmental process that ultimately causes the condition, perhaps by influencing how the brain wires itself up.

Now, Yale scientist Jessica Mariani and her colleagues, writing in the journal Cell, have shown that at least part of the problem relates to how the brain develops and produces nerve cells of the correct types, and how those nerve cells subsequently connect together.

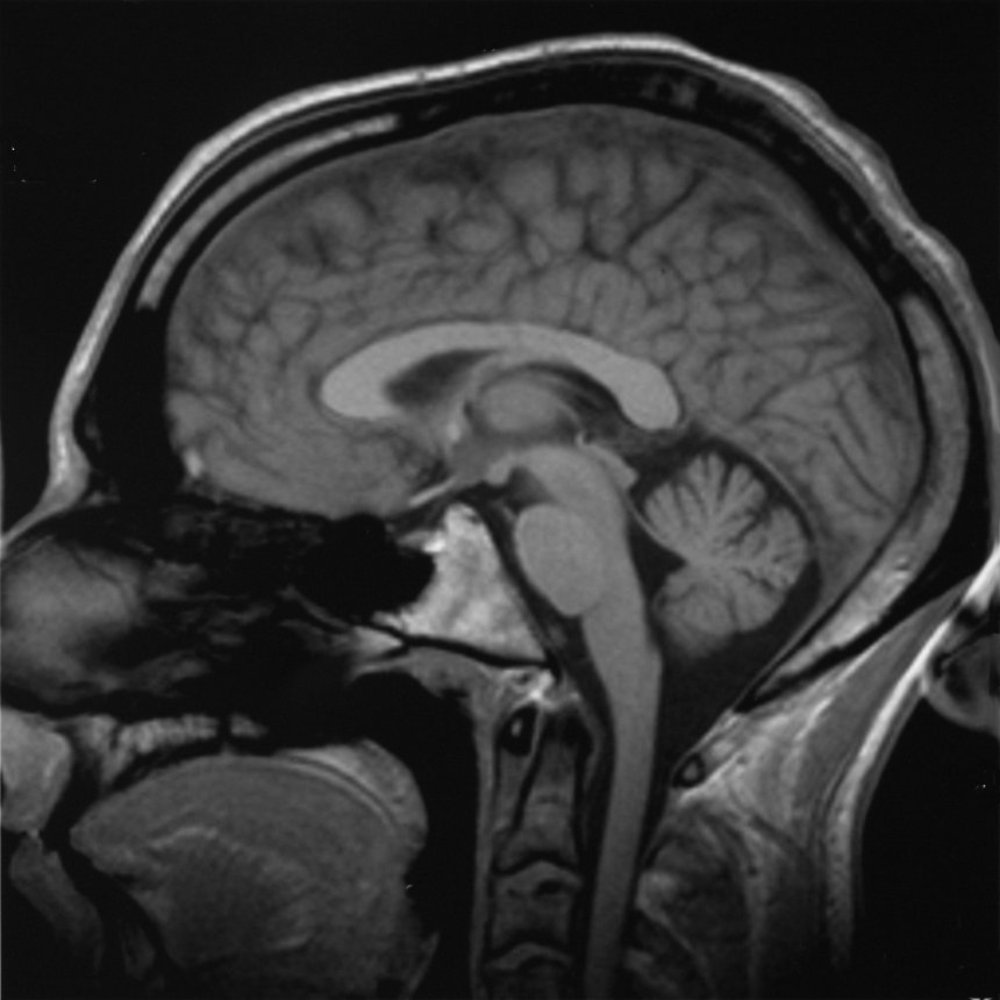

The Yale team transformed skin cells from four autistic patients into stem cells that, using culture techniques, grew into tiny balls of brain tissue called organoids. They also produced equivalent brain organoids for the patients' healthy parents so that the relative numbers and types of cells, gene profiles and electrical activities of the tissues could be compared between each.

Consistently, in the autism organoids the numbers of inhibitory nerve cells, which use the transmitter chemical GABA, were over-represented in the neuronal population.

At the same time, the number of connections made by these inhibitory cells was larger than normal, and genetic signals corresponding to factors that provoke the development of inhibitory nerve cells were higher than in the control tissues.

More generally, the levels of more than a thousand genes were found to be off-kilter in the autism organoids compared with the parental control tissue, although there were no specific changes, or mutations, in these individuals in any of the genes previously linked to autism.

One gene that was showed the greatest level of over-expression was FOXG1. This has been shown previously to play a role in the development of the forebrain.

The fact that it was expressed at levels more than 13 times above normal led the team to speculate that it might be responsible for the altered neuronal profile seen in the autist organoids.

In line with this hypothesis, when the team used a modified virus to "knock-down" the activity of the gene in subsequently produced organoids, the imbalance of inhibitory over excitatory nerve cells that they had seen previously was reversed.

While the underlying reason for the gene abnormalities isn't known yet, the team suggest that studying the process will lead to a clearer understanding of the causes of autism, but, in the nearer-term, could also be used as a potential biomarker to test for autism during pregnancy.

Comments

Add a comment