The field of arterial graft surgery looks set to take a big leap forward thanks to a breakthrough by US scientists.

Writing in Science Translational Medicine, Shannon Dahl, a researcher with the North Carolina-based bioengineering company Humacyte, has described a method for making large, very strong, biocompatible artery grafts. Until now, if a patient required a replacement artery - for instance to bypass a blocked coronary vessel - the ideal source was usually one of their own long saphenous veins, which run up the legs. And although for larger graft requirements - such as repairing an aortic aneurysm - PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) replacements are very effective, this material is unsuitable for smaller vessels because it tends to become blocked with blood clots after a matter of months.

In general, except where pieces of a patient's own vessels are used, most vascular grafts (75%) work for fewer than three years. Motivated by this relatively poor performance, Dahl and her colleagues have taken a different approach - by growing new arteries.

In general, except where pieces of a patient's own vessels are used, most vascular grafts (75%) work for fewer than three years. Motivated by this relatively poor performance, Dahl and her colleagues have taken a different approach - by growing new arteries.

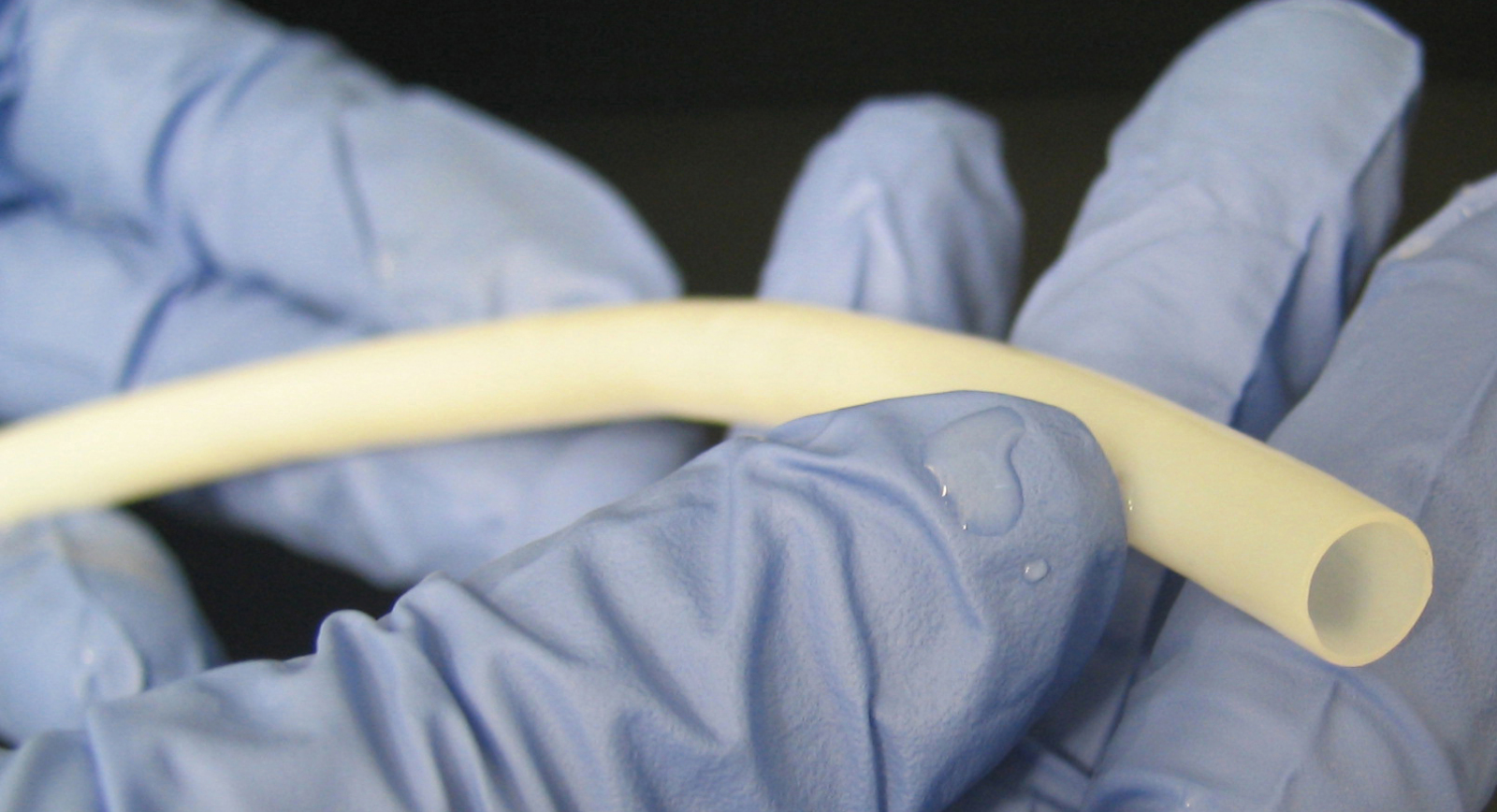

The method pioneered by the team involves starting with a tubular scaffolding made from a biodegradable material called polyglycolic acid (PGA). These scaffolds are immersed in a culture solution containing smooth muscle (SM) cells of the type normally found in the walls of blood vessels. Over a seven to ten week period the smooth muscle cells proliferated over the PGA scaffold, dissolving and replacing it with a matrix of connective tissue. Next, detergents were used to "decellularise" the nascent vessels, leaving behind just a tough connective tissue "tube".

Pressure tests showed that these structures could withstand over 3000 mmHg, fifteen times normal human blood pressure. Next, to verify their clinical potential, the team implanted the grafts, which are dubbed TEVGs - Tissue Engineered Vascular Grafts - into baboons, cats and dogs, where they remained long-term patent in over 80% of cases. Subsequent study of the implanted grafts showed that the animal's own endothelial cells, which line the vasculature, had grown in to coat the interior surfaces of the grafts.

Critically, there was also no evidence that the animals' immune systems were reacting to the implanted vessels. This suggests that the technique could be used to rapidly produce safe, non-immunogenic replacement vascular segments for human recipients, including patients requiring vascular access for kidney dialysis, and in large amounts.

Comments

Add a comment