Researchers have discovered a chemical signal secreted by blood cells that  prevents arteries from furring up again following injury or angioplasty.

prevents arteries from furring up again following injury or angioplasty.

Called cathelicidin, the substance, which also has antimicrobial properties, is secreted by white blood cells called neutrophils that flock to sites of tissue injury and inflammation.

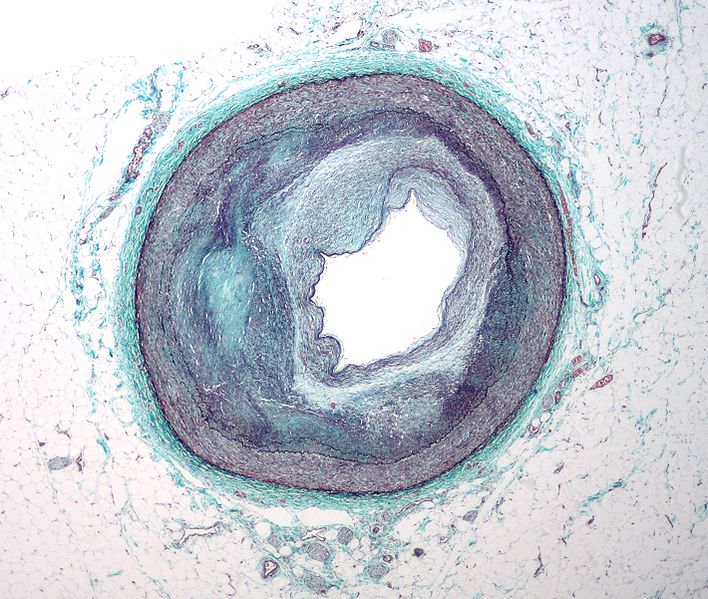

In tests on mice, University of Munich researcher Christian Weber and his colleagues found that removal of the neutrophils from circulation following an arterial injury caused vessels to become blocked by an overgrowth of tissue called neointimal material, the growth of which was triggered by the damage.

But when neutrophils were present, the researchers found, the cells clung to the injured parts of the artery and deposited cathelicidin locally. This then recruited a separate population of blood vessel-rebuilding cells called early outgrowth cells. These proliferated and secreted repair factors, reassembling the endothelial lining that paves and seals the inside surfaces of arteries. Re-establishing the endothelium in this way appears to prevent the potentially lethal neointimal overgrowth.

This means the discovery could also have  implications for the process of angioplasty in which doctors use a tiny balloon to open up blocked blood vessels. Usually during this procedure a small metal cage called a stent is inserted to hold open the artery afterwards. But this can trigger inflammation, leading to neointimal overgrowth and re-stenosis, or blockage, of the artery.

implications for the process of angioplasty in which doctors use a tiny balloon to open up blocked blood vessels. Usually during this procedure a small metal cage called a stent is inserted to hold open the artery afterwards. But this can trigger inflammation, leading to neointimal overgrowth and re-stenosis, or blockage, of the artery.

To get around this problem, the latest generations of stents are impregnated with anti-proliferative drugs designed to block the growth of the neointimal tissue. But whilst they are very effective in this role, ironically 30% of patients who receive these so-called "drug-eluting stents" develop complications including the formation of blood clots inside the vessel. Doctors think this occurs because the drugs don't only block the growth of the neointimal tissue but also prevent the smooth endothelial lining being re-established. So a cathelicidin-secreting stent might be able to overcome these difficulties.

With this in mind, the team, who have presented the work in Science Translational Medicine, engineered a cathelicidin-impregnated stent that was inserted into the carotid arteries of a group of experimental mice. A second group of control animals received stents that lacked cathelicidin but were otherwise identical.

When the arteries from the two groups of animals were compared 4 weeks later, the arteries of the cathelidicin-stented mice showed significantly less narrowing.

According to the team, "although it remains to be seen whether this effect will be reproduced in humans, cathelicidin may prevent stents from causing the very problem they are supposed to treat and thus improve therapy for severe atherosclerosis."

Comments

Add a comment