A neurochemical circuit that enables the brain to control the immune system has  been revealed for the first time.

been revealed for the first time.

Scientists have known for many years of the powerful connection between the psyche and the functioning of the immune system, although the neurological underpinnings of the relationship have remained shrouded in mystery.

Now a team at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in New York and the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, writing in the journal Science, have unravelled the workings of the communication system linking the nervous system and immunity. And what's really surprising is that immune cells themselves act as go-betweens to transmit chemical messages from nerve cells to other immune signalling cells.

Previous work conducted by Kevin Tracey, the senior author in the present study, had shown that stimulating the Vagus nerve, which runs from the brainstem to supply tissues in many parts of the body, could stop the immune system pumping out inflammatory signals. The signal responsible seemed to be a well-known nerve transmitter chemical called acetyl choline. But the wrinkle in the story was that the Vagus nerve did not appear to be producing it!

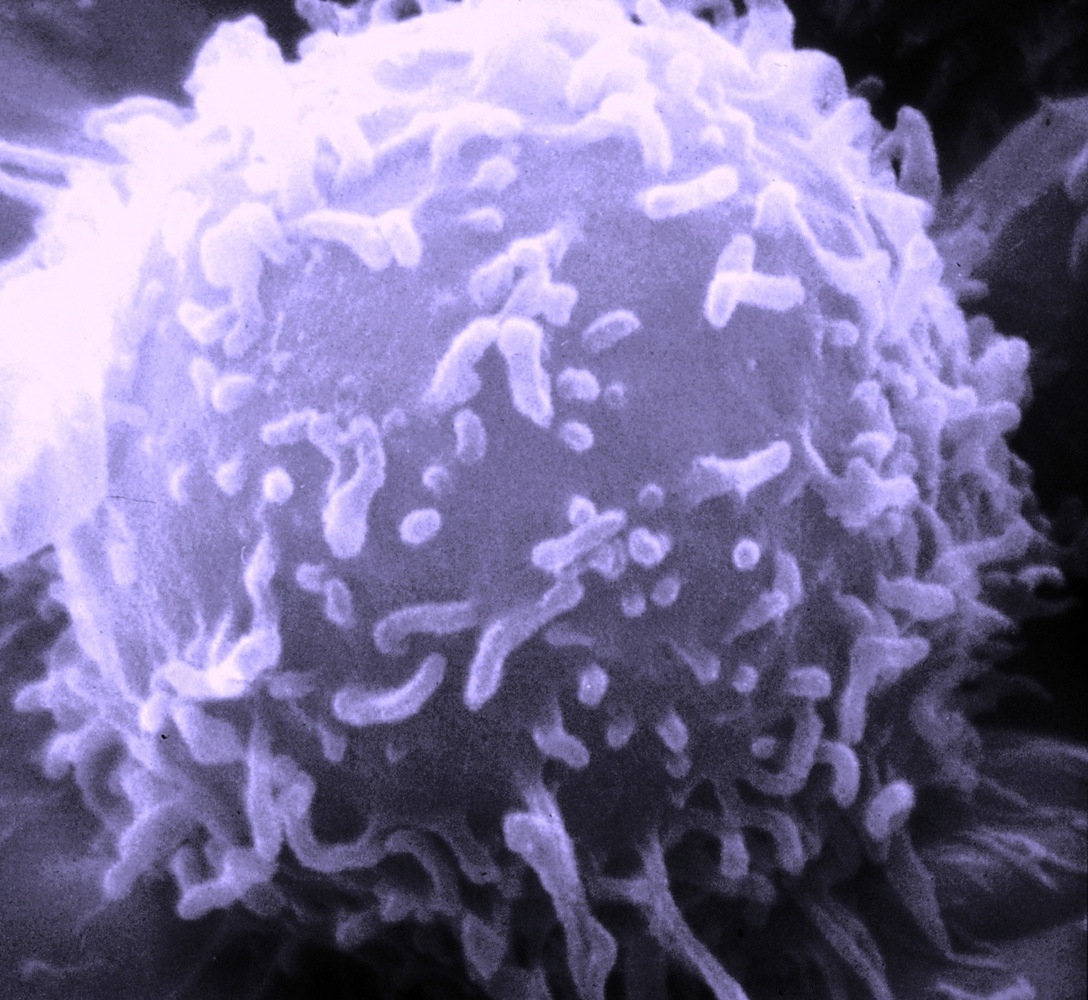

Now, by studying the spleens of experimental mice, the team have solved the mystery. White blood cells in the spleen called CD4 lymphocytes, when activated by inflammatory processes, become sensitive to the nerve transmitter chemical noradrenaline, secreted in the spleen by the splenic branch of the Vagus nerve. The CD4 lymphocytes themselves then secrete acetyl choline, which in turn switches off the production of inflammatory chemicals by other nearby cells.

The team proved this by carrying out experiments in mice lacking their own CD4 cells; these animals did not switch off the supply of inflammatory mediators when their Vagus nerves were stimulated. But when activated CD4 cells were transfused into the animals from donor mice, they immediately began to churn out acetyl choline, inhibiting the inflammatory process. Switching off the ChAT gene, which makes acetyl choline in these cells, also prevented any response.

Importantly, as the team point out in their paper, the regulatory system they have discovered is not confined to the spleen because the same sorts of CD4 lymphocytes are present throughout the body, particularly in lymph glands and specialised lymphoid tissue in the intestine called Peyer's Patches. This means that the system almost certainly plays a major role in controlling inflammation throughout the body and manipulating it could hold the key to controlling autoimmune and other related disorders...

Comments

Add a comment