A Nature paper reveals an exciting fossil story that shows some very strange extinct marine invertebrates called anomalocaridids were around for a lot longer than we previously thought...

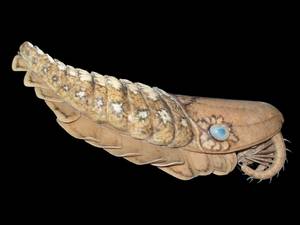

Anomalocaridids look a bit like a cross between a cuttlefish and a woodlouse - with a long segmented trunk, flat swimming 'lobes' running down their sides, two segmented appendages on the front that look a bit like prawn tails, and a circular mouth on the underside of the head that looks like a pineapple ring. In fact, each of these separate elements - the body, the appendages and the mouth, were once thought to be from three completely separate animals. It was only in the 1980s when the late great Harry Whittington, and Derek Briggs (one of the authors on this paper) found complete specimens with all three of these features present, in the Burgess Shale in Canada, and realised they were actually part of one organism, which they christened Anomalocaris. They were very agile, formidable predators of the oceans, moving by undulating their lobes a bit like a ray or a cuttlefish, and crushing prey in their hard circular mouthpiece.

Anomalocaridids look a bit like a cross between a cuttlefish and a woodlouse - with a long segmented trunk, flat swimming 'lobes' running down their sides, two segmented appendages on the front that look a bit like prawn tails, and a circular mouth on the underside of the head that looks like a pineapple ring. In fact, each of these separate elements - the body, the appendages and the mouth, were once thought to be from three completely separate animals. It was only in the 1980s when the late great Harry Whittington, and Derek Briggs (one of the authors on this paper) found complete specimens with all three of these features present, in the Burgess Shale in Canada, and realised they were actually part of one organism, which they christened Anomalocaris. They were very agile, formidable predators of the oceans, moving by undulating their lobes a bit like a ray or a cuttlefish, and crushing prey in their hard circular mouthpiece.

There are four other genera of anomalocaridids as well as Anomalocaris and they're found in Early and Middle Cambrian sites ( so from around 542-501 million years ago) from the United States, Australia, Russia, Poland and China.

This paper, published in Nature by Peter Van Roy, and Derek Briggs, describes new specimens of anomalocaridids from the Fezouata Biota in southeastern Morocco, which is from the early Ordovician Period around 488-472 million years ago. These represent the youngest examples of anomalocaridids by about 30 million years, and provide a link to the great-appendage arthropod Schinderhannes from the Early Devonian.

The specimens they found were large as anomalocaridids go too - some up to a metre long, and they were found within a rich mix of other species - showing that they were still an important part of the marine ecosystem at this time.

Another key finding is the dorsal blades - flat structures found all the way down the back of the specimens. These were one thought to be scales, but here the authors suggest they may have performed some sort of respiratory function, possibly because of the high oxygen requirement of an active swimming lifestyle.

These new Moroccan specimens are the youngest examples (in geological terms) of anomalocaridids yet found and the authors suggest that they may have died out after the diversification of other groups like predatory eurypterids - huge sea scorpions - and cephalopods during the Ordovician.

Comments

Add a comment