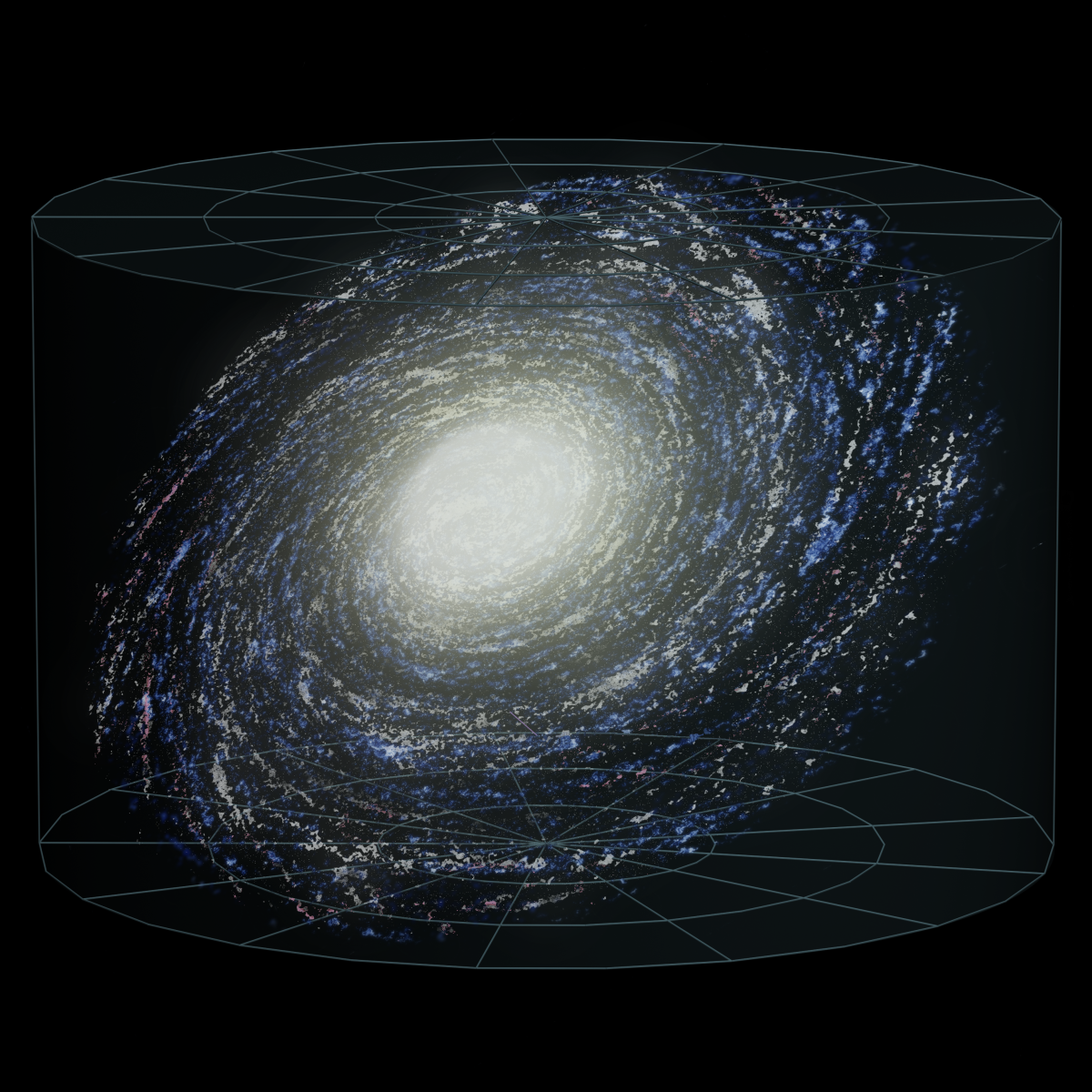

Chris - First this week, the Gaia space mission which was launched on the 19th of December is now orbiting around a virtual point in space  which is called L2. It's about 1.5 million km from Earth. Gaia's goal is to create the most accurate map yet of the Milky Way. This week, its 1 billion pixel camera was tested successfully which is presumably a very big relief for Cambridge professor Gerry Gilmore who's leading the project. Hello, Gerry.

which is called L2. It's about 1.5 million km from Earth. Gaia's goal is to create the most accurate map yet of the Milky Way. This week, its 1 billion pixel camera was tested successfully which is presumably a very big relief for Cambridge professor Gerry Gilmore who's leading the project. Hello, Gerry.

Gerry - Hi, Chris. Good to see you again.

Chris - Are you a relieved man?

Gerry - Doubly actually. I was at the launch and one felt really quite relaxed after it was over, seeing Gaia flying off so successfully.

Chris - How much money was invested in that?

Gerry - The lifetime cost of the project is getting on for a billion Euros, 600 or 700 million pounds.

Chris - Or a third of an LHC to put it another way, I suppose.

Gerry - Well, it's the people's lives that is their real cost. There's hundreds of really smart engineers that have devoted decades to this so that's the bit you can't get back.

Chris - The announcement this week that the camera works, so when you put one of these things into space, how do they power them up? Do they do it system by system to do a series of checks to make sure that everything works sequentially then?

Gerry - Yes. The whole turn on process is still underway, but you turn on the really smart brains of the system which themselves then turn on other bits of the system and so on. There are some bits like the atomic clocks that take weeks to settle down, so they're turned on early and they're still settling down. So, Gaia won't actually be in full science operation for another three or four months yet. But as the systems are turned on and tested, we then know whether they're working or not. The really critical systems which is the computing, the brain, the clocks, and the camera and telescopes, they're all working fine. That's a really magnificent tribute to the people who built it and a spectacular relief for those in it.

Chris - How do you know that the camera is working correctly because all you get back is what it tells you it's seeing?

Gerry - So essentially, all Gaia is is two telescopes feeding a very, very large camera. These things are billion pixels, biggest camera ever put into space. It's about a metre long. Compared to the one in your phone, which is about the size of your little finger nail, this thing is the size of your tabletop. What it's going to do is essentially feed down a high definition movie for the next 5 or 6 years. And so, the first frame of that movie is down and it looks good. So, by comparing it with previous studies of the same cluster which by pure coincidence happen to be a study I did using the newly repaired Hubble Space telescope in the late 1990s. So, it's pure chance that that happens to be the same cluster. But by comparing it with those Hubble measures, we know how sensitive the camera is, we know how accurately the things in focus. So, we know how clean the optics are and all the news is good. I mean, there are few technical things that will come out in the next week or two, but fundamentally we know the mission is going to work. It's terrific!

Chris - Congratulations! Have there been any problems or has it all been a bed of roses so far?

Gerry - No, there's always a few problems. Everybody knows the famous spectacular Hubble problem and Gaia's predecessor actually went in the wrong orbit. The rocket didn't fire because some twit left a bit of cloth in it. But Gaia has nothing like that. there's a few little technical issues that we'll be able to work through. But fundamentally, it's looking good.

Chris - How long before the data begins to land on your desk here in Cambridge so that you can begin to see these amazing maps in extraordinary detail, emerging of our galaxy?

Gerry - Well, we're processing the test data right now. That's where that image came from. So, we know what's going on. We're contributing to the team that's actually testing out the hardware and checking that everything is working, and putting the telescope in focus. That's actually a non-trivial thing to do. It'll take another month yet before it's perfectly in focus. But then the real science data will start coming in in April. So then we'll do the science verification. So, that's the real hard - how good is the science going to be. So, we know that technically, the thing is looking promising. About April, we'll come back and we'll show you the first science results and then we'll expect to be in full routine, doing nothing but exciting science from May onwards to another five or six years.

Chris - You must come back and tell us how you're getting on. Gerry thank you very much and congratulations. Great to have you on the programme. Gerry Gilmore from Cambridge University's Cavendish laboratory.

Comments

Add a comment