Scientists studying tumour samples pancreatic cancer victims have made a surprising discovery - the disease appears to take a very long time to develop before it begins to spread.

The prognosis for pancreatic malignancies is almost universally dire with a 5 year survival rate of about 5-10%. This is because the disease tends to reveal itself very late, by which time the tumour has often already spread - metastasised - to other tissues.

But this grim outcome could be improved thanks to a new study published in the journal Nature and carried out by Johns Hopkins-based scientist Christine Iacobuzio-Donahue and her colleagues. This team obtained fresh autopsy tissue from 7 patients who had died from pancreatic cancer.

But this grim outcome could be improved thanks to a new study published in the journal Nature and carried out by Johns Hopkins-based scientist Christine Iacobuzio-Donahue and her colleagues. This team obtained fresh autopsy tissue from 7 patients who had died from pancreatic cancer.

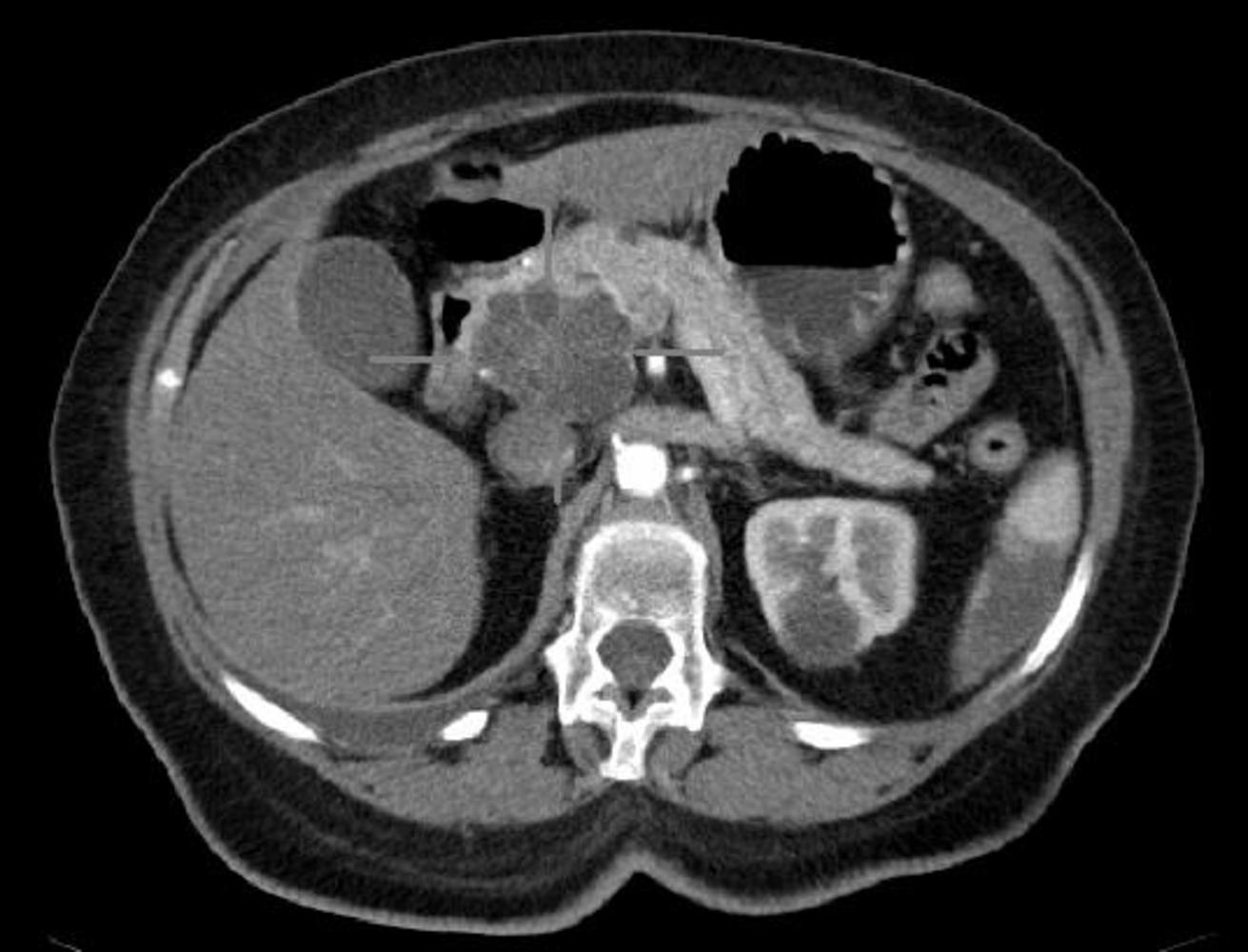

By extracting viable cells and DNA from the tumour deposits in these patients, including from both the primary pancreatic tumour and the metastases, the researchers were able to build an evolutionary tree tracing the acquisition of the DNA mutations that triggered the tumours and then the disease spread. The bulk of the DNA damage linked to the disease, they found, was already present in the primary tumour, and they could trace "sub-clones" of the primary that had given rise to different metastatic events around the body.

This result shows that, contrary to prevailing wisdom - that potentially cancerous cells spread early and then turn into tumours later - does not apply to pancreatic cancer. Moreover, using mathematical algorithms to track the rate of disease progression, the team were able to determine that it takes on average 11.7 years before the first cancer cell develops within a high grade lesion, then a further 7 years before the cancer the potential to spread and, finally, about 2 and a half years from then until a patient's death. This suggests that early detection and early intervention could dramatically improve what is currently an appalling prognosis.

- Previous Super-Waterproof Cotton

- Next New form of transistor developed

Comments

Add a comment