On this week's NewsFlash, we discover a viral cause of hypertension, find out how bees stick to petals like velcro, and discuss a new, super-dense deuterium - 130,000 times denser than water! Dr Joe Grove joins us to chat about World Hepatitis Day, and Sarah Castor Perry takes us back to this Week in Science History.

In this episode

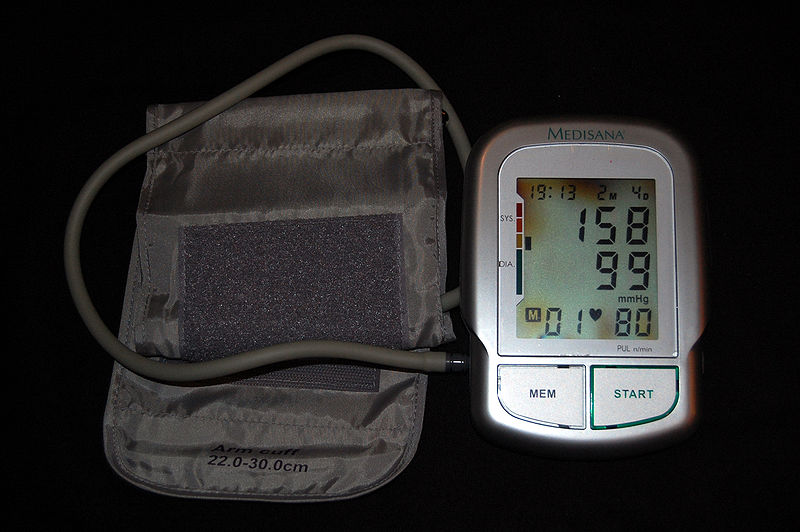

Virus to blame for blood pressure

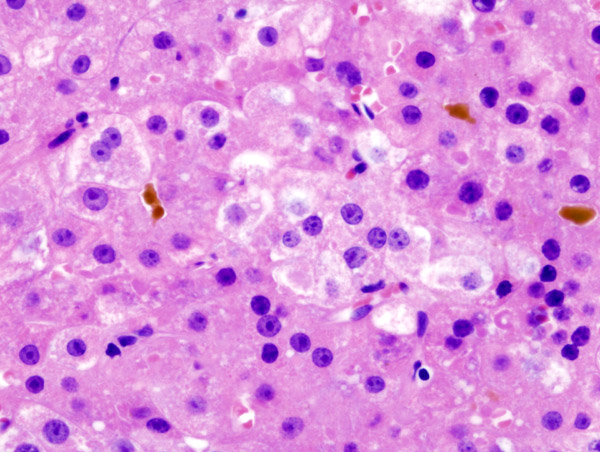

US Scientists have discovered that a common human viral infection may be linked to hypertension, also known as high blood pressure.

Writing in PLoS Pathogens, Beth Israel Deconess Medical Center researcher Clyde Crumpacker and his team infected mice with the rodent equivalent of CMV (cytomegalovirus), which infects 80% of human adults. They found that, compared with uninfected controls, the CMV-exposed animals had significantly higher blood pressure in the weeks after the infection.

Writing in PLoS Pathogens, Beth Israel Deconess Medical Center researcher Clyde Crumpacker and his team infected mice with the rodent equivalent of CMV (cytomegalovirus), which infects 80% of human adults. They found that, compared with uninfected controls, the CMV-exposed animals had significantly higher blood pressure in the weeks after the infection.

They also fed a second group of mice on a high-fat diet and infected half of them with the virus. In the CMV-exposed group the animals again developed hypertension but also showed signs of early atherosclerosis (arterial disease).

To find out why, the team studied the animal's blood vessels and found that the virus was establishing a persistent infection in the vessel wall that led to the production of inflammatory hormones called cytokines including IL-6, TNF-alpha and MCP-1, which have been linked previously to vascular disease. The team also found increases in the activity of two genes that directly control blood pressure - renin and angiotensin.

Next, to find out whether the results also apply to humans the team infected human umbilical cord blood vessels with human CMV with the same results. These findings are important because CMV is part of the herpes virus family, members of which characteristically establish life-long "latent" infections, meaning that CMV is well-placed to provoke long-term injury to blood vessels that could lead to vascular disease. The next step will be to discover whether there is a real association between human onset of hypertension and CMV infection, which increases in prevalence with increasing age, just like blood pressure diagnoses...

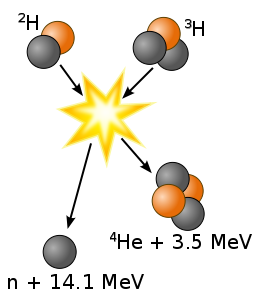

Ultradense deuterium

For a long time researchers have been interested in hydrogen because it is the most common element in the universe and because it fuels the nuclear fusion reactions that power stars. Nuclear fusion involves reacting light atomic such as hydrogen, or its isotopes deuterium or tritium together to form heavier elements. The problem is that in order to get the nuclei to react you have to get them very close together and because they repel one another this is very difficult. To get a decent rate of reaction you need to either have a very high temperature and or a very high density which is difficult because hydrogen is a gas.

For this reason scientists have been interested in finding other forms of hydrogen which are much more dense, one that has been known about for a long time is metallic hydrogen which exists in the centre of planets such a Jupiter and has a density close to that of water.

For this reason scientists have been interested in finding other forms of hydrogen which are much more dense, one that has been known about for a long time is metallic hydrogen which exists in the centre of planets such a Jupiter and has a density close to that of water.

However researchers in Gothenburg, Sweden have been splitting deuterium molecules up using a catalyst and an electrical field, and studying what is produced by firing a laser into the products which will rip electrons off a pair of atoms. This means that you have two positively charged nuclei very close to each other, which immediately fly apart in what's called a coulomb explosion.

The researchers were measuring the energy of the particles being thrown off and discovered some which appear to have over 60 times as much energy as those from metallic hydrogen. This would relate to a bond length of about 2.3pm or a material with a density of 130,000 times that of water.

This is very interesting because if the nuclei start off this close together they would need far less energy to fuse than conventionally, although of course the lifetimes are measured in nanoseconds and the scientists have only made truly microscopic amounts of this material so far.

Natural Velcro helps bees get a grip

Flowers evolved a natural form of Velcro on their petals to help insects get a grip making it easier for them to pay a visit and collect nectar while carrying out that vital job of pollination.

Publishing in the journal Current Biology, Beverly Glover from Cambridge University led a team of botanists who set out to find a solution the long-standing mystery of why the flowers of many insect-pollinated plants are covered in cells shaped like minute cones or pyramids.

Glover and her team made artificial epoxy resin flowers both with and without the microscopic patterns of cone-shaped cells. They put sugar solution in the centre of the flowers and presented them to bumblebees in the laboratory giving them a choice of the smooth or rough petals.

When the petals were laid out horizontally, the bees had no particular preference for the rough or smooth petals, visiting each about half of the time. But when the petals were sloped at a steep angle, up until they were vertical, the bees preferentially visited the rough petals rather than the smooth ones.

High-speed films of the foraging bees revealed why they preferred visiting the rough petals. On the vertical smooth flowers, the bees were unable to get a grip: their feet were constantly slipping and they had to keep beating their wings to stay on the flower. Meanwhile on the rough petals, the bees quickly found a foothold and they could settle down and stop beating their wings, which saves them a lot of energy making their foraging visits far more efficient.

Previous studies have shown that bees can tell the difference between rough and smooth petals, probably by feeling them with tiny sensory hairs on the ends of their antennae. Glover and the team also tested out bees with a range of real snapdragon flowers, some with normal rough petals and a mutant strain with smooth petals. They found that when the flowers were held vertically, the bees visited the rough petals more often, presumably because they could get a better grip.

So it seems that providing insects with a safe landing pad, is one rather elegant and simple way that flowers make sure they pass on their genes to the next generation.

Droplet Display technology

Most computer and TV displays work by actually emitting light, whether this is produced by making a phosphor screen glow in conventional TVs and plasma screens or from a fluorescent tube behind an liquid crystal panel in a modern LCD displays. This is great in a dark room but if you are outside on a bright day the sunlight completely overwhelms the light from the screen and of course making all that light uses up a significant amount of power so the displays tend to be power hungry.

The solution is to make a display that works like a piece of paper, reflecting light from outside, so no matter how bright it gets you can still see the picture, and you are not producing light so it needs less power. There are several technologies which do this in black and white such as the e-ink on some e-book readers, but they only change very slowly.

The solution is to make a display that works like a piece of paper, reflecting light from outside, so no matter how bright it gets you can still see the picture, and you are not producing light so it needs less power. There are several technologies which do this in black and white such as the e-ink on some e-book readers, but they only change very slowly.

However researchers from the University of Cincinnati may have a solution that will give you full colour at video speeds. Their technology works using droplets of ink sandwiched between two hydrophobic surfaces. Normally surface tension pulls an ink drop into a sphere and it sits in a small well in the centre of a pixel. But if you apply a voltage the ink is attracted to the outer surface and it spreads out over the whole of the pixel changing the colour to that of the ink. If you remove the field the droplet shrinks back again, and if you make the pixels small it can switch very quickly. At the moment they have prototypes which can switch in 50ms which is almost fast enough for video applications but they think that they can improve it to about 1ms which is far faster than is needed.

This is still very much a prototype but they have monochrome displays working and they see no reason that they couldn't be made to roll up, so in a few years time you may be carrying one of these displays around in your pocket.

13:44 - World Hepatitis Day

World Hepatitis Day

Dr Joe Grove, Birmingham University

Chris Smith - Now it might surprise you to know that around the world about one person in every 12 is actually living with a chronic infection of their liver, usually hepatitis C or hepatitis B, and those numbers totally overwhelm the numbers of people with pandemics that we are well acquainted with, things like HIV and flu. Not many people actually know about the massive disease burden that's caused by these infectious causes of hepatitis and so to try and remedy this on the 19th May what has been set up is being called World Hepatitis Day and all over the world people will be gathering to try and run events to raise awareness of this. At the University of Birmingham researchers including Dr. Joe Grove will be doing just that and he is with us now to explain a bit about what they are trying to achieve. Hello Joe.

Joe Grove - Hi Chris.

Chris Smith - Welcome to the Naked Scientists. So tell us what you are actually hoping to achieve with the World Hepatitis Day.

Chris Smith - Welcome to the Naked Scientists. So tell us what you are actually hoping to achieve with the World Hepatitis Day.

Joe Grove - Okay, so like you said World Hepatitis Day would be a lot like World AIDS Day, to raise national awareness of the problem and we are holding an event to highlight the interesting scientific and clinical work that's done here in Birmingham. The aim of the event is to raise awareness with the public and hopefully reach out to people to get tested. Also to engage with the patient community that's in the U.K. and to highlight the important work that's done at the University.

Chris Smith - What will you be doing during the day to tell people a bit about hepatitis B and hepatitis C?

Joe Grove - So we have a couple of MPs, Dr Lynn Jones who is our local constituency MP and Dr Brian Iddon who is a member of All-Party Hepatology Groups. They decide liver policy in parliament. They will be coming down. Also representatives from the local press and the local community and the patient community. We will be giving them a series of talks to outline the scientific research we do here on hepatitis C specifically but also the work that's done to treat both hepatitis B and C in Birmingham and the clinical research such as clinical trials that are carried out here. And then we will be giving them a tour of the laboratories and also the clinical research facility in the hospital.

Chris Smith - So let's just look at the actual disease that these agents cause and why you need to raise awareness about them. What are hepatitis B and C and why are they a problem?

Chris Smith - So let's just look at the actual disease that these agents cause and why you need to raise awareness about them. What are hepatitis B and C and why are they a problem?

Joe Grove - Hepatitis simply means an inflammation of the liver and if you had acute hepatitis, that is a short hepatitis, that's not necessarily a problem. Viruses like hepatitis A or E cause acute hepatitis that self-resolve. Hepatitis B and C are capable of establishing a persistent infection. So individuals may be infected for the duration of their life. Now this becomes a particular problem because if you have hepatitis over this extended period of time you will start to get other symptoms such as liver cirrhosis and possibly even liver cancer. In the case of hepatitis C there are up to 500,000 people in the U.K. with an infection but 80% of those do not know about it.

Chris Smith - So that makes it a major issue because if they don't know it they can pass it on because these are of course blood-borne viruses. You spread them by sharing blood, sharing needles, having sex with people. So people, if they don't know they've got it can pass them on. So I guess raising awareness about them in the general population is very important because that encourages people to get tested.

Joe Grove - Yes, of course and also there are actually treatments. It is possible to treat hepatitis C and you have a reasonably good outcome of treatment. We have around 50% of patients resolving. However, people often don't seek medical attention until the disease has become particularly apparent and by which stage it is harder to treat. So if there is anyone out there who are worried that they may have been exposed, they should get tested and then they got a much better chance of getting a resolution to the illness.

Chris Smith - Thank you very much Joe. That was Dr. Joe Grove who is a researcher at Birmingham University and he is hosting what will be Birmingham's contribution to World Hepatitis Day on Tuesday - the 19th May 2009. Their events are actually on Monday 18th, so that's tomorrow. So thank you very much Joe Grove for joining us on this week's Naked Scientists.

Chris Smith - Thank you very much Joe. That was Dr. Joe Grove who is a researcher at Birmingham University and he is hosting what will be Birmingham's contribution to World Hepatitis Day on Tuesday - the 19th May 2009. Their events are actually on Monday 18th, so that's tomorrow. So thank you very much Joe Grove for joining us on this week's Naked Scientists.

18:06 - This Week in Science History - The Death of Eduard Bruckner

This Week in Science History - The Death of Eduard Bruckner

Sarah Castor-Perry

This week in science history saw, in 1927, the death of Eduard Bruckner, the German geographer and climatologist who was one of the first to discuss whether changes in climate were due to a natural cycle or down to humans, and how this climate change would affect our future.

Climate change is a big topic these days, with Oscar winning films being made about it and the newspapers splashed with stories of how spring flowers are blooming earlier and London will be under water in 50 years. But the study of global climates, or climatology, was a highly debated subject even in the late 19th century, when it was more about how changes in climate have or will affect human civilisation rather than the chemical and physical aspects of our climate. Bruckner was a central character in the debate over the economic and political consequences of climate change at the turn of the century. He studied the history of changes in sea levels and glaciations as he knew that 'proof of past climate change points to the possibility of future climate change'. With titles like 'How constant is today's climate?' and 'The influence of climate variability on harvest and grain prices in Europe', his papers could have been written in the last few years, but were in fact written over 100 years ago, and Bruckner himself has been largely forgotten.

Climate change is a big topic these days, with Oscar winning films being made about it and the newspapers splashed with stories of how spring flowers are blooming earlier and London will be under water in 50 years. But the study of global climates, or climatology, was a highly debated subject even in the late 19th century, when it was more about how changes in climate have or will affect human civilisation rather than the chemical and physical aspects of our climate. Bruckner was a central character in the debate over the economic and political consequences of climate change at the turn of the century. He studied the history of changes in sea levels and glaciations as he knew that 'proof of past climate change points to the possibility of future climate change'. With titles like 'How constant is today's climate?' and 'The influence of climate variability on harvest and grain prices in Europe', his papers could have been written in the last few years, but were in fact written over 100 years ago, and Bruckner himself has been largely forgotten.

He was born in Germany in 1863 and grew up in Russia before going to university in Munich. He completed his doctorate on glaciation and at the age of 25, he was made professor of Geography at the University of Bern. Throughout his academic life he published articles in newspapers and gave public lectures, in order to bring his ideas on climate variation to the public.

The discussions amongst scientists at the turn of the 20th century were very similar to those had today between scientists, boards like the International Panel on Climate Change and governments, but all the changes and initiatives suggested then for slowing or reversing climate change, such as replanting forests across North America to reduce drying were forgotten about in the early 20th century in the face of other global problems, particularly the two World Wars.

The discussions amongst scientists at the turn of the 20th century were very similar to those had today between scientists, boards like the International Panel on Climate Change and governments, but all the changes and initiatives suggested then for slowing or reversing climate change, such as replanting forests across North America to reduce drying were forgotten about in the early 20th century in the face of other global problems, particularly the two World Wars.

One piece of work that Bruckner is remembered for is his work on what is now known as the Bruckner cycle - a naturally occurring 35 year cycle of periods of wet, cold weather alternating with warm/dry periods. He tried to predict when the dry or wet periods would fall and also predicted that they would have varying effects across the globe on agriculture, immigration and economics. Warmer, dry periods would increase agricultural productivity in Europe, whilst decreasing it in a larger continent such as North America, making it less likely that people would emigrate from Europe to North America in that period.

Bruckner and his contemporaries recognised that there were climate oscillations that occurred periodically, but also that there was progressive climate change, probably driven by human actions such as deforestation.

Bruckner felt he had a social duty to inform the public about his discoveries and that scientists had a key role to play in advising governments on changes that needed to be made to help to reduce the human impact on the climate. He was well respected in his field and published many papers raising concerns about human impact on climate change that although over 100 years old are still relevant today, but due to events of the first few decades of the 20th century he and his work have sadly been somewhat forgotten. He deserves to be remembered as one of the pioneers of an area of science that is now at the forefront of government policies and front page news stories around the world.

Related Content

- Previous Waggle Dance Evolution

- Next Technology - Iron, Glass and Slag

Comments

Add a comment