Adventures in Satspotting

What happens when we turn our astronomical instruments back to planet Earth? With the launch of over 12 satellites, Europe's version of GPS, Galileo, will be operational very soon but why are space scientists getting all excited about it? This month on Naked Astronomy, Graihagh Jackson is all about the satellites.

In this episode

00:56 - How do you get a satellite into space?

How do you get a satellite into space?

with Professor Martin Sweeting OBE FRS, SSTL

Space is one tough cookie to crack: satellites have to work in extreme  temperatures, radiation and a vacuum. There are now over 3,000 satellites orbiting Earth but how did we get them up there in the first place? Graihagh Jackson finds out...

temperatures, radiation and a vacuum. There are now over 3,000 satellites orbiting Earth but how did we get them up there in the first place? Graihagh Jackson finds out...

Graihagh - The first artificial satellite to launch was the Soviet Sputnik 1 mission in 1957. A polished metal ball, it was just over half a metre in diameter with four long, radio antennae which beamed beep beep beep back down to the Russians, letting them know it had reached orbit safely. It was this Boule that sparked the Space Race between Soviet Union and the Americans...

... 3, 2, 1, 0. All engines running. Lift off, we have a lift off. 32 minutes passed the hour. Lift off on the Apollo 11.

... is arguably why we saw men on the moon a mere 12 years later...

Buzz Aldrin - It's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

Graihagh - Fast forward 60 years and guess what? Space is no less political. The launch of European satellite constellation, Galileo, was largely propelled by our over-reliance on American navigation systems. What would happen if we fell out? They could jam the signal and because we're so dependent on these satellites, it would render us extremely vulnerable.

Think about it, we use this technology every single day like satellite navigation...

If you're driving anywhere in your car you probably use satellite navigation to get where you're going.

Graihagh - And then there's the stuff you never even think about....

Well actually every time you go and get money out of your ATM, all of these are coordinated through satellite based timing systems.

Graihagh - And the scientific scientific and military applications that we touched on before...

There are all kinds of political reasons why you might want one.

Graihagh - And it's all seemingly invisible...

But how the heck do you get from concept to object orbiting Earth? Today, the life and death of a satellite and the future of these metallic beasts.

Martin - I'm Martin Sweeting. I'm the Executive Chairman of SSTL and Chairman of the Surrey Space Centre.

Graihagh - And when I looked you up on the internet, I have to admit you have a number of letters after your name so you've clearly done something quite amazing in terms of industry and space and satellites.

Martin - Well... First of all I have to say that I have to own up to saying that I've had a great deal of fun and the letters sort of came afterwards. They weren't the objective, I had a lot of fun. What we did, particularly in developing small satellites over the last 30 years, was recognised by people and the letters followed.

Graihagh - I met Martin at a conference at the Royal Academy of Engineering earlier this month. Given that SSTL - or surrey satellite technology limited - have launched more satellites than I can count on my fingers and toes put together, I asked him to talk me through how a satellite is born.

Martin - Well... I suppose the first thing to start with is, fairly obviously, is to decide what it is you want the satellite to do. So, are you going to take images of the earth, are you going to provide communications, or whatever, and then you go about deciding how big the satellite is, how much power it's going to need. If it's going to carry instruments, how big are those instruments. And then that gives you an idea of the physical size and the power demands of the satellite. Once you've done that, obviously there's a lot of detail that goes into the design of the spacecraft, both the electronics and mechanics. Then, of course, having more or less got that sorted out, you actually have to build it. That's, to some extent, the fun part; trying to find neat technical solutions at the right cost to meet the objectives is a big challenge. Yes, space is inhospitable, you can't go up and fix it but actually, 20 minutes of launch is the most physically demanding because everything shakes and rattles. After that, there's no shaking and rattling whatsoever. It's a very benign environment but the environment can then suffer temperature extremes if you don't design it right and that, of course, can play havoc with the electronics, and the biggest difference between being in space and on the ground is radiation. On the ground we are protected by the atmosphere and by the Earth's magnetic field and in orbit we're not.

Graihagh - It's a long list of things to think about... but that's not all.

Martin - You then need to look for, basically, a rocket that's the right size. It's a bit like going down to the shops and you have to choose a rocket that's the right size. One that's too big will be delightful but much too expensive, one that's too small won't fit, so it's a question of optimising that. And then, of course, there's only a limited number of suppliers of rockets and those are all over the world in different countries so there's a fair amount of international awareness and negotiation that goes into it. You have to go through all the contract conditions, how do you ensure it against failure or it falling out of the sky on somebody and things like this, so there's many legal and contractual aspects apart from the technology that goes into it.

Graihagh - And then, when you've got your satellite in the sky, you can breath easy, right?

Martin - And one of the things we have to remember is that you can't go up and fix it, so if something goes wrong and you get the blue screen of death on your satellite, you can't just go round the back and press the reset button. You have to either find ways that you can solve it from the ground or you can switch to redundant or alternative systems which would allow you to recover the functionality and control of the satellite.

Graihagh - It sounds like a lot to worry about...

Martin - Yes, and actually, that's not the end of the story because once the satellites launched into space, you have to be able to communicate with it and control it from the ground and if you think that a satellite in lower orbit is travelling at 7 kilometers a second, you see it for 10 minutes and then it disappears, so you've got to be able to ensure that the satellite operates safely for most of the time when you can't talk to it. Just building and launching the satellite is actually only half the story. Controlling it, making sure it's safe, getting the best out of it for a long period of time so you get your money the back on your investment is just the bigger problem

Graihagh - And how long does this take from conception all the way to getting it safely up into orbit?

Martin - Well it depends. Government missions, particularly science missions, may take 1 or 2 decades. Commercial missions make take 4 or 5 years. Some of the latest developments in small satellites have accelerated that so it could be twelve months or less. So now we're seeing small missions which are going from concept to being ready for launch in certainly less than 12 months, sometimes 9 months or thereabouts. So the tempo is increasing for the smaller scale satellites but for very exotic, big satellites, maybe costing a billion dollars or so, typically it's a decade.

Graihagh - And Galileo is an good example of this. The first of 30 satellites were catapulted into space in 2005. Now there are 12 up there. When the project is complete, they'll be 30 satellites dotted above Earth providing us with a reliable and very precise location data (think cm accuracy rather than the metres accuracy we're used to). But won't this just make us more reliable on global navigation systems? Is that a good thing?

Martin - Most people don't realise how dependent they are on space, which is good but also frightening. As our modern society takes advantage of space, we also become dependent on it and if we're dependent on it, there are some vulnerabilities. Some of those vulnerabilities are fairly obvious, if a satellite fails then you lose the service but others are slightly less obvious. One is solar activity; we haven't had very large solar storms for over a 120 years, 150 years now. If we were to get a very large solar storm, that would affect satellite communications, and timing, and navigation, and so on and, of course, it is vulnerable to malicious cyber intrusions, not necessarily more than anything else, but it's one of the vulnerabilities. And so if we do lose the benefits of space we will feel it, much more now than we would have done 30 or 40 years ago.

09:32 - The impending launch of Galileo

The impending launch of Galileo

with Dr Chaz Dixon, Technical Director of GNSS at Catapult.

Europe's Galileo will soon be operational, providing us with much more accurate  navigation but why do we need it given we have GPS and other systems in place? As Chaz Dixon explained to Graihagh Jackson, there are some politics involved as well as the need for better accuracy...

navigation but why do we need it given we have GPS and other systems in place? As Chaz Dixon explained to Graihagh Jackson, there are some politics involved as well as the need for better accuracy...

Chaz - The thing that excites me is that Galileo, which has been coming and coming and coming for so many years, is finally going to be here and we're going to have huge capabilities coming down the pipeline, higher accuracy, higher availability through that multi-GNSS world. I'm a long term GNSS geek.

Graihagh - That's definitely a very geeky thing to look forward to, I'll give you that...

Chaz - I'm afraid so. Long term nav geek.

Graihagh - You've made me excited through for it so... here, here!

I just love it when you meet someone who is enthralled as Chaz is about their work. Now, back to Galileo, why is he so excited?

Chaz - The whole space is growing very much at the moment. We've had GPS now for 20 years, the American system. Europe is just about to introduce it's own so that will be declared operational this year. It's not yet complete but it will be in an operational state and we'll be able to use that combined with the American GPS system, the Russian Glonass, and the Chinese are also developing a system called Badowl. So all of that's combining to give more capability to an individual user/receiver.

Graihagh - Why do we need another one given that you've just mentioned there are several already there?

Chaz - Well it's a complex answer to that question. There are all kinds of political reasons why you might want one. If we look purely at the engineering side, typically there would be 8 or 10 satellites visible with an open sky but with high rise buildings both sides of the road, a GPS receiver in a mobile phone, on a watch, in a car, might only be seeing one or two signals at any given time...

Graihagh - And you need three?

Chaz - You need four typically to navigate and there's a complexity if you use multiple systems because they use different time standards so typically, when you add each system, you may need an extra measurement. So with GPS you need four measurements, if you add GPS to Glonass you might need five measurements, if you add Gallileo you might need six measurements, but each of these constellations is typically 30 satellites. The one or two GPS combined with the one or two Glonass, with the one or two Galileo, etc, mean that you have all of the necessary positioning capability in a dense urban environment.

Graihagh - It doesn't just mean I can find my way around London easier - As more of us live in cities, we'll also need more frequent trains, as those of us who frequently play a game of sardines on the commute to work will be wanting sooner rather than later. Because railway signalling systems are still relatively unsophisticated, it means that for safety reasons trains have to be well-separated. With Galileo, that becomes much less of an issue. And then there's the whole driverless car thing...

Chaz - That becomes exciting into a future where the controller of a vehicle might not be a person, because a person will drive their car along a street and not in a field. But now, if you put a robot in charge of that vehicle, you have to give the robot the capability to know the difference between an urban street and the countryside and it has to be able to do that in the fog, or in the rain, or in whatever conditions it is.

Graihagh - So that's when GPS becomes really, really important and having that accuracy and that coverage?

Chaz - Exactly so and that multi-GNSS capability in an urban environment becomes really important.

Graihagh - Will you be getting a driverless car? Will you be trusting GNSS?

Chaz - Not this year. Maybe one day!

13:18 - Why the satellite industry is booming

Why the satellite industry is booming

with Catherine Mealing-Jones, Director of Growth at the UK Space Agency

Why, during the economic downturn has space been doing so well finacially? It's possibly one of the most expensive ventures around! Catherine Mealing-Jones told Graihagh Jackson why is't been such a success story...

possibly one of the most expensive ventures around! Catherine Mealing-Jones told Graihagh Jackson why is't been such a success story...

Catherine - Well I think it's almost impossible for anyone to have a day of life without using satellites in some way. So, if you switch on the weather forecast, most of the long range forecasting has come from satellites. If you're driving anywhere in your car you're probably use satellite navigation to get where you're going. There's all sorts of things that are monitoring our planet so really it's an absolutely integral part of our life - satellite technology - although most don't really think about it. Whether it's TV, telephones, all of these things can be delivered via satellite.

Graihagh - I guess it's just kind of invisible. It's there, it's omnipotent but not really that clear.

Catherine - No I think that's right. In a way that's what good technology should be. You should have a focus on good technology that you're using without necessarily thinking about how it's delivered. So yes, that's absolutely true with the satellite sector.

Graihagh - But the real stand out thing for me at this conference is that the satellite industry is BOOMING. Why, when the rest of us have been sat in an economic downturn has space - possibly one of the most expensive ventures around - been living the dream?

Catherine - Yes, it's been a spectacular success story. The sector continues to grow at about 8.5% over the last few years which has really bucked the trend of the economic downturn, which has been fantastic. Turnover annually is just under 12 billion a year here in the UK. All in all it's a really good success story and something that should really attract people to work in the sector and be part of the sector because I think it's set to continue - that trend of growth.

Graihagh - Why do you think has been so successful? What makes it different from all the other industries?

Catherine - We were talking earlier about its applicability to daily life and I think there's something in there. I think there's been some huge investment, for example, for us here in the UK. At European level we've got the Galileo satellite navigation programme and the Copernicus observation programme, so there's going to be a real wealth of new data and new technology available. And then the other thing, here in the UK, we've just got a lot of people who've got the innovation and the knowhow to be able to exploit the technology. So, I think it's partly, as well that we've had a very intensive long term strategy between government, industry, and academia who've come together to put together the actions that we need to really capture the growth in the sector. So the whole ecosystem around space and space infrastructure is really strong here in the UK and I think that sets us fair for growth for the foreseeable future really.

16:18 - Prospero: Britain's pride and joy

Prospero: Britain's pride and joy

with Doug Millard, Deputy Keeper, Technologies and Engineering at the Science Museum in London

It's been over 50 years since Prospero launched and its long-since been  decommisioned but what happens when a satellite 'dies?' Graihagh Jackson went to the Science Museum to meet Doug Millard...

decommisioned but what happens when a satellite 'dies?' Graihagh Jackson went to the Science Museum to meet Doug Millard...

Doug - When you launch a satellite or a crew into space, you can't just use one vehicle because as you burn up the fuel (the propellants), you get an increasing amount of dead weight, if you think about it, which is why we have these rockets in stages. In a way, you have a sequence of rockets each firing one after the other. So the first stage of Black Arrow, that uses a Gamma rocket engine. If you look at the back of it you can see that each rocket chamber is arranged in pairs and they can swivel and that helps steer the rocket. So, it gets it off the ground, starts to steer it and the second stage here, that takes over and that takes it a little bit higher still. And then finally the third stage, which is the Waxwing rocket just above our heads, that has the satellite attached to it and that gives it the final kick into orbit and... mission accomplished.

Graihagh - I heard it was a bit of bumpy ride on the way up there - it wasn't all plain sailing?

Doug - It was yes. The launch was successful but we can see one of the upper stage rockets called Waxwing and that was a little bit too enthusiastic. Once it has put Prospero into orbit, it carried on firing and bashed into it and knocked one of Prospero's radio aerials off. Fortunately, it didn't disrupt the mission but it didn't shut down quite as quickly as it should have done.

Graihagh - And just if we look at Prospero, it does look like a little puck almost with - is it solar panels all the way round the outside?

Doug - Yes it is. It's covered in fillets they call them of different surfaces. Most of them are, as you say, solar panels so they're generating electricity to help power the satellite. But you've also got some experimental surfaces - you can just see a white one there, and they're looking at different types of material and how they behave in space (in the vacuum of space) where there's radiation. There's also a little detector called a micrometeoroid detector, which just registers all the little bits of dust that were impacting the spacecraft. So it's telling us as much as possible about how satellites could be launched and survive and also about the space environment.

Graihagh - It basically set out to find out as much as it could about what life for a satellite would be like, out in space. Up against the radiation, vacuums, the cold, the heat, it's not a particularly friendly place to be! Prospero engineers hoped that once we knew exactly what they were up against, they could build other satellites that would last many, many years...

Doug - So it was a test satellite. It was telling us the rudiments of how to make a satellite that will last many years.

Graihagh - And indeed it has because it's still up there in space now.

Dough - It's still up there. It's orbiting almost over the poles (we call it a polar orbit) and it takes about 100 minutes to go round the Earth but it's still up there. We were communicating with it for many years after it's launch.

Graihagh - Indeed, a BBC TV series called Coasts 'talked' to it back in 2004, but they're not alone, many people have listened out for it's tail-tail roar, like Greg Roberts.

SFX

He's what you might call a radio ham - this is where hobbyists like Greg point their radio antennas at the sky and record these 'weird' signals from satellites and then do some detective work to find out which metal lump they had come from.

SFX

But sadly, it appears that Prospero is no more...

Doug - Presumably the systems have finally succumbed to what is a pretty harsh environment (lots of radiation and temperature extremes) and, as far as I know, it no longer talks to us.

Graihagh - But people did try from UCL, I believe, a could of years ago to see if they could communicate with it?

Doug - Yes, for many years we tried to communicate with it every year on its anniversary and then in 2011, as you say, the UCL Physics Department tried to see if there was any life there but I'm afraid there was no indication that it was still 'alive and kicking'.

Graihagh - Is that a fairly typical story of a satellite then that it's still orbiting forever, presumably?

Doug - Well you can launch a satellite into a variety of orbits depending on what sort of mission you want to carry out. So, for example, let's think of the television satellites, the satellites that beam television direct to our dishes on the side of our houses. They are a long way out - they are 36,000 kilometers out into space and they're going to stay up there for a long time, you know thousands of years...

Graihagh - Thousands of years!

Doug - Thousands of years.

Graihagh - How can they withstand the freezing cold, there's solarwinds, there's radiation - there's so much to contend with?

Doug - Well, once you're moving in space, unless you have something to obstruct your movement, you'll carry on moving almost forever. When you're that far out, there is really no vestiges of the Earth's atmosphere to slow you down. The lower the orbit, for example Prospero, is only a few hundred kilometers above the Earth, so toward the end of this century it's orbit will start to decay quite rapidly and eventually it will burn up in the atmosphere - a fiery end.

Graihagh - It will burn up? I just presumed we'd start seeing it raining satellites at some point.

Doug - Well Prospero's quite small and none of it will survive - it will just be one brief fireball. Satellites are really astonishing. We tend to either take them for granted or not really think about them at all even though we're using sat-navs and DBS broadcasting and so on, but they are made to survive in space without needing a fix. You can't send round and engineer or a technician to fix a satellite that's gone wrong. You might be able to beam up some new software to remedy a fault but that's not always the case. So when you've invested millions and millions of pounds in a satellite and it's launch, you want to make sure it works so they really are remarkable technologies. The problem we face is because they are so successful and because most of them stay up there a long time, space is getting rather crowded and there is a risk of satellite collision.

Graihagh - What would happen in an incident like that? I'm assuming that all these orbits are tracked so that hopefully they don't collide but, obviously, accidents happen?

Doug - Accidents do happen. There is an unwritten protocol that the orbit is chosen so that no collision can occur but, occasionally, these things do happen. There was a collision between a Russian satellite and another one not so many years ago causing a tremendous amount of debris and that is tracked. You can keep an eye on something about the size no smaller than a grapefruit. Fortunately with that particular collision most of the junk is now coming back down to Earth and it will burn up in the atmosphere.

24:56 - Satellites around the Moon

Satellites around the Moon

with Professor Martin Sweeting OBE FRS, SSTL

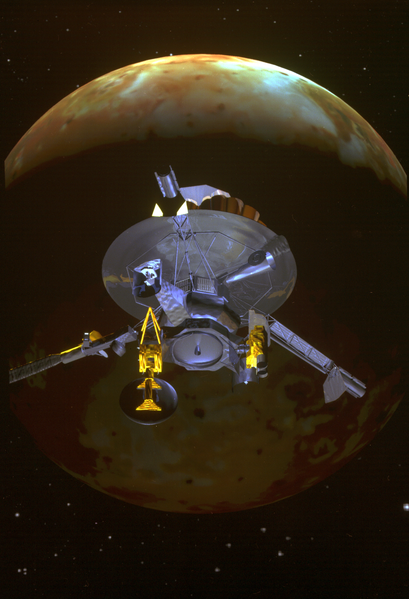

What's the future of satellites? Well, one day, they will help us explore the  Moon and Mars, as Martin Sweeting explained to Graihagh Jackson...

Moon and Mars, as Martin Sweeting explained to Graihagh Jackson...

Martin - I think it's inevitable that we will see sustained human inhabitation on the Moon. That's probably a good stepping stone for Mars and what we will see is that we'll need the same space infrastructure that we have on Earth placed around the Moon and on Mars.

Graihagh - That's like something out of a Sci-fi movie?

Martin - Yes, but there's a lot of things that were in Sci-fi movies 20 years ago that we take for granted. I can remember as a kid going to the B movies and seeing these black and white science fiction and they were rather old even then. Science fiction movies where doors magically opened as you came in and that people have little, what now we would look at as a smart phone. These things were considered absolutely outlandish and they were very simple things which now we don't even give a second thought to so, 20 years hence, anything's possible.

Comments

Add a comment