Connie won a meteorite

Fellow Naked Scientist Connie Orbach won a meteorite and so Graihagh Jackson made it her mission to find out as much as possible about this hunk of space rock, including how she might go about finding one of her own...

In this episode

00:52 - Connie won a meteorite!

Connie won a meteorite!

with Connie Orbach, Naked Scientists

Naked Scientist Connie Orbach won a meteorite and so Graihagh Jackson made it her mission to find out as much as possible about it. But first, how did Connie get it in the first place?

mission to find out as much as possible about it. But first, how did Connie get it in the first place?

Connie - I'm not going to lie, I've never wanted a meteorite before, but now I have one I'm incredibly happy.

Graihagh - And it's come on quite a journey to get here because we have been waiting in the office for weeks in anticipation of this meteorite.

Connie - I think I'd say over two months - it's been a long time! A long time coming, yeah. So I won it; it was an incentive to fill in a feedback form. I never win anything and then I got an email eight months later, I think probably (I'd forgotten about it completely) saying I'd won the meteorite. Amazing!

And so they said it would take a while because they said "we have to order it". And I said "where from, do you order it from space?" How do you order a meteorite in this day and age? But no, I think they just ordered it from the meteorite store which, apparently, exists somewhere.

Then it arrived but I wasn't here.

Graihagh - Oh yes, that's it - I'd forgotten! It arrived in a box and me and Georgia were like 'the meteorites here!' We sent you a message didn't we? An instant message pretending to open the package.

Connie - Yeah, you sent me lots of like pictures. One was actually of just a big stone you'd found saying we'd got your meteorite. It's just a meteorite but I was actually but when I thought that you potentially opened it without me I was really angry. But I got back and you hadn't so we opened it and it's not very big. I'm holding it now and it's...

Graihagh - About an inch long, isn't it?

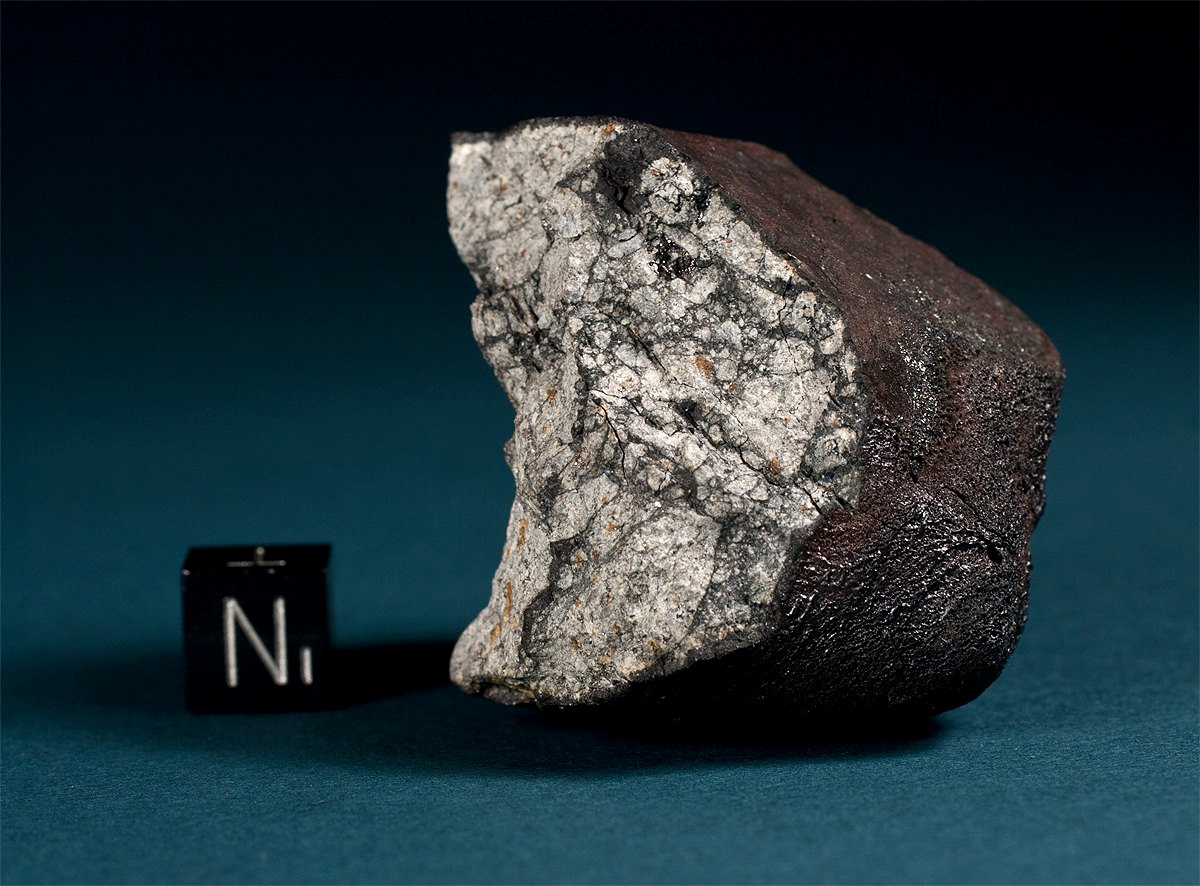

Connie - Yeah, yeah, about an inch long, half an inch wide and kind of bumpy. It's black but with a silver kind of tinge to it when you look at it in the light. And the thing that really strikes you when ou get this it it's really, really heavy.

Graihagh - Yes, I'm still shocked. I mean, even though we were pretending to open it I'm still shocked. I thought it was packaging that made it how heavy that is. I think that's maybe a kilo, maybe?

Connie - You think? It's definitely at least a bag of sugar so that's how I'd do my measurements, so it's at least half a kilo. And it feels like a visual illusion every time you're holding it, I think, because it just doesn't match up but my brain thinks something is wrong!

And the other thing it came with is a lovely little sign telling me this about it.

Graihagh - Dare you pronounce what it says?

Connie - So obviously, I'm fluent in Spanish - Campo del Cielo.

Graihagh - Very good.

Connie - From Gran Chaco - oh this is tricky - Gran Chaco Gualamba, Argentina. Found - and so this is how I know they didn't order it from space - found in 1576. It's really old! I mean it's space rock so it's really old, but it's really old to this world too which I thought was quite amazing. And then it's kind of got what it's made of and the main thing is iron and that's why it's so heavy. And probably, I should have filled this in by now but there's an empty box where someone didn't know what do. It's says specimen weight but it doesn't say the answer so we can't tell you, we just have to guess by bags of sugar!

Graihagh - Do you know anything more about it? I mean I'm thinking, meteor, meteorite, comet. I'm not entirely sure I know where these things overlap.

Connie - I have no idea.

Graihagh - Given we've all been so excited, none of looked anything more into it.

Connie - No, not at all. I was just excited I was getting a meteorite but, actually, probably not sure what that is! I just know it's space rock of some sort.

Graihagh - OK it's your birthday soon, so I'm going to make it my mission to find out as much as I can about this rock.

Connie - Yeah, two weeks. So you've got two weeks to find out, and if you can get some form of certificate, I'll be particularly happy.

04:40 - Spot the difference: Meteor, meteroid...

Spot the difference: Meteor, meteroid...

with Dr Carolin Crawford, University of Cambridge

Do you know your meteors from your meteorites? Neither did Graihagh

Jackson, so she met Carolin Crawford to find out...

Jackson, so she met Carolin Crawford to find out...

Carolin - I should have brought some of my Mars and Moon ones in - I keep them at home because they're too precious.

Graihagh - Yes, she is talking about meteorites from the Moon and Mars that just happened to fall on Earth and she is Dr Carolin Crawford - lover of space rock, naturally, but also an astronomer at Cambridge University. We met to compare our rocks but first things first - what's the difference between a meteor, meteorite and meteoroid but a comet and an asteroid?!

Carolin - Yes, it is complicated and astronomers do love our terminology. So, you've got lots of lumps of rock; the debris that you said floating around in the solar system.

Now if it is made of ice - like a frozen iceberg 5-10 kilometres across or smaller, we tend to call it a comet even though it might have bits of dirt and dust within it. So comets are the icy bodies.

Asteroids are the rocky debris. And we won't talk about things called Centaurs which are half ice half rock. They're out beyond Neptune - we won't worry about them so much. But, basically you've got your asteroids which are rocky and you've got your comets which are icy.

Now a meteoroid is like a tiny asteroid. You're talking about a few microns across to a few metres across in size. So it's just debris, like the asteroids, left over or fragments from a collisions or protoplanets, that's been hanging around for billions of years in the solar system and floating around between the planets, around the Sun following their own orbits.

Now as soon as that meteoroid starts to enter Earth's atmosphere it becomes a meteor. That's what you know as you're shooting star and that's when you see it burning up in the atmosphere. It sort of excites the air molecules and you get this trail of ionised particles which shine, and you also get the lump of rock, even if it's tiny, it will still give of an amazing amount of light because it's travelling quite fast. Most of them disintegrate in the atmosphere completely but, if they survive to hit the surface of the Earth, then they become a meteorite.

So that's the distinction: Meteoroid when it's in space, meteor when it's in air, and meteorite when it's sitting on the ground.

Graihagh - Simplez.

Carolin - Did you bring this meteorite?

Graihagh - I did.

Caroline - OK let's have a look - see which one you got.

Graihagh - How much do you know about meteorites?

Carolin - I'd say it's a nickel/iron one.

Graihagh - Gosh - that's impressive! I was going to bring out the label because I couldn't even remember what it...

Carolin - Sikhote Alin?

Graihagh - No.

Carolin - So it's not Sikhote Alin. It's not Campo del Cielo because it's metal rather than...

Graihagh - Oh - controversial!

Carolin - Oh it is! It's Campo de Cielo.

Graihagh - I'm going to ask you how much you can tell me about this because this is Connie's meteorite that she won and, other than giving it a quick look up on the internet, we know nothing.

Carolin - This is one of the more common falls.

Graihagh - Ah, OK.

Carolin - You've got two very famous falls - you've got the Campo del Cielo. And this is part of the Sikhote Alin fall. I mean I like this one - you can see how it's just sort of melted as it's fallen through the air. It's all kind of deformed and ruffled up - I like it particularly.

Graihagh - It reminds me of... do you remember The Futurist (the painters) - The Futurists. You know how they had these very choppy, jagged types of paintings - that's what it reminds me of.

Carolin - Or it just looks like a parrot! It is deformed. I mean you look at that and you see a mangled bit of metal and you think gosh, that metals gone through a lot to get to be that shape. So I think this is part of the Sikhote Alin fall, so this fell in the Sikhote Alin mountains in 1947.

Graihagh - So you're one's much more recent?

Carolin - Yes, this one they actually saw the fireball through the sky. They saw the meteorite coming in and later found the pieces. Whereas the Campo del Cielo, we think fell thousands of years ago but it was only more recently found.

Graihagh - You've mentioned two types of different falls there. Is it quite rare for this sort of stuff to fall to Earth or is it quite common?

Carolin - You have stuff coming into the atmosphere the whole time. You've got millions of meteors happening daily, it's just that most of them are tiny. A shooting star you can get from a thing about the size of grain of sand. Most disintegrate in the atmosphere but, even so, you get a lot that land on the Earth or, in fact, fall into the ocean probably at a rate of about 15 million kilogrammes per year. There's a huge amount of stuff that is just continually piling onto the Earth

You don't look like you believe me.

Graihagh - Well, I was really pleased that we'd won there so now you're telling me (I say we), Connie has won this and it's not even that rare.

Carolin - They are rare. I mean it sounds like a lot but, in terms of volume and mass of the Earth, it's miniscule. Also, what you've got there is one of the metal ones - they're the rarer ones.

Graihagh - The reason why I ask if it's rare, and I'm glad you say it's rare, I've got this meteorite for the weekend now. If I was to go away and sell it, what sort of price does this thing fetch?

Carolin - For the size you've got there I would guess about £60 or something.

Graihagh - Oh, that's pretty reasonable!

Carolin - I think it's pretty reasonable.

Graihagh - Dinner out! Because now I'm going to go everywhere I walk I'm going to have my eyes on the ground looking for these things.

Carolin - You get three basic types: The most common ones are the ones that are rocky. Then you get the iron ones, so that's iron and nickel alloy. And then you get stoney iron which are the mix of the two.

This is a rocky one - well we call it stoney and you see it's got a sort of black crust on the outside. Now that would have been the outside of a meteorite as it fell through the air so this is where it had been burnt. We call this the fusion crust because it's where the rock has fused, effectively, under the extreme conditions as it falls through the air. It gives you a bit more of a character.

And then this is just a segment, a fragment of the meteorite and you can see, when we open it up, it's much more rocky on the inside of the meteorite again. There's a little tiny bubble of metal there...

Graihagh - Oh yeah. Tiny, like a pinhead.

Carolin - Yes, but just a little inclusion of the metal alloys within it.

This is an example of a stoney one that is very nice because you see it's got a mottled appearance.

Graihagh - Dare I say, a bit like sometimes when I'm walking down the street and you see all the little bits of rock within, what's it called - pebbledash is what I'm thinking but in a miniature polished form. Is that a terrible thing to say?

Carolin - No. You're getting the idea across beautifully there. It is just speckled and you've got these almost like spherical - we call them inclusions - little bubbles of dust and carbon materials that's held within the silicate base.

Graihagh - So where do these things come from? I mean I know they're space rock but why do they end up falling here on Earth for people like us to scurry around and collect them?

Carolin - They come from a number of different places, but you're quite right, they're lumps of space rock or, if you like, space metal that are floating around there orbiting round the Sun. Now some of them, especially those rocky/stoney ones, are left over from the original solar system formation. They are bits that just didn't get incorporated into being planets.

Or they could be fragments of asteroids. You know, you can imagine protoplanets in the early solar system, asteroids now colliding and scattering fragments off.

And then you have some that are really exciting and they're where a meteorite has impacted another planetary body. So it's something like the Moon or Mars or say Vesta, the largest asteroid in the asteroid belt. And when the meteorite impacts that body, it send an ejector out but because things like Moon, Mars, Vesta don't have so much gravity, not all of it falls back down to the planet. It then goes out into space and starts orbiting the Sun and, maybe millions of years later, it happens to fall on Earth.

So some of these meteorites are bits of Mars, they're bits of the Moon, or bits of Vesta.

Graihagh - Oh, are you about to show me a rock from Mars?

Carolin - No, this one's a bit of Vesta.

Graihagh - Wow!

Carolin - Which is surprising common. If you look at Vesta, this is the object that's about 500 kilometers across in the asteroid belt, it looks a bit more more like a punctured football. It's got a huge sort of gouge out of the southern pole and that's where we think it underwent a huge collision sometime ago in its past. So there are lots of fragments of Vesta around and this is one here.

Graihagh - How do you know that?

Carolin - You know because of the mineral makeup. I was telling you you've got all these different origins for different kinds of meteorites and, looking at the chemical composition of these rocks, you can tell a lot about whether they're pristine parts of the solar nebula or they've come from bodies that have undergone what we call geological differentiation. So you've started to have that geological processing, the separation out of the metals and the sort of silicate crust.

So, when you hold something like your Campo del Cielo that's completely metal, that would have come from the inside of one of these differentiated bodies. So like a small asteroid that was forming or a protoplanet that was forming before it got smashed so you've got a bit of the core part of the asteroid there.

A lot of these stony meteorites are much more of the pristine debris left over from the early solar system.

Graihagh - So why is it them that we're interested in things like 67P, and we've sent out Roseta and we've seen Philae land on the comet? Why though if all this stuff is falling down on Earth all of the time?

Carolin - there's a lot of science you can only do when you're in contact with the astronomical body, like the comet Nucleus, and that was what was important about the Philae lander. And, of course, you've got to remember that comets are mostly ice, not just water ice, but also methane ice, and ammonia, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide. If you want t understand the icy part of the comet, you've basically got to go out there.

14:47 - What does a comet smell like?

What does a comet smell like?

with Matt Taylor, ESA Mission Scientist

Rosetta has managed to sniff the comet 67P and scientists, like Matt Taylor, have reconstructed what it smells like! Graihagh Jackson went along to give it the sniff test...

Matt - So my name's Matt Taylor. I work for the European Space Agency on the Rosetta mission that's gone to a comet and is still there until September. Was that OK?

Graihagh - That's wonderful. Tell me about the Rosetta mission, what did it set out to do?

Matt - Rosetta is a mission to a comet. It set out in 2004, took ten years to get to its target comet and why do we go to comets? We go to comets because we consider them to be representative of the building blocks of the solar system. So, by studying a comet, you get an idea of what the conditions were, what the material that went into building the solar system. In fact, there's material that we found from the comet by Rosetta that actually predates the Sun. So it's really the primordial soup, the ingredients for that soup, and we get a picture of it by looking at this comet.

We sent the spacecraft up in 2004, it chased down the comet over ten years. In 2014, we turned the spacecraft back on because we'd had the time period where we were in hibernation, we caught the comet, we landed on the comet with Philae and, for the last two years, we've been orbiting the comet and measuring various things on the comet. Looking at it's surface structure and how it evolves in time because a comet is really interesting in that when it goes past the Sun it becomes very active. There's a lot of ice inside it that throws of tons of gas and that heats when you get near the Sun, and then starts to drop off and move away from the Sun.

With Rosetta we've sat next to it all this time observing how that stuff evolves, what the surface does, the surface changes. We think about a metre of the surface disappeared in the time that we've been at the comet with Rosetta, and so that's why we're here talking about Rosetta.

It's actually coming to an end. By September this year we're running low on power, data volume as well. Getting the data down from the spacecraft, it takes over half an hour for the signal to come from the spacecraft. It's a time to say goodbye to Rosetta and that's in September.

And we're going to say goodbye by doing something we've always wanted to do, and always try to do, is get as close as possible to the comet. And we will do that, and we have done that by saying to the engineers we want to crash onto the comet and that enables you to get as close as possible. And so that's what we do and September 30th is when we will say goodbye to Rosetta by crashing into the comet.

Graihagh - Sounds like a sad day?

Matt - I think it's going to be a day of mixed emotions. I know, talking to some colleagues who work on the operations solidly, the ones who drive the spacecraft, that's the end of the mission for them. That's really it, that's it, the end of!

But for us that work on the science side, it's actually the beginning. It's when, although we have been doing science already, it's when you only have time to do science. And that's when we'll be doing the big leaps and bounds and the breakthroughs with Rosetta when we have all that time to do the science, and there's decades of work to do on this data.

Graihagh - I've heard something rather intriguing in that you've done something here where I can sniff the comet 67P?

Matt - Yes. There is a number of, how can I put it, aromatic compounds on the comet that we thought would be really nice to engage people with by saying, this is the stuff. You can visually see the tail and everything but you can't see the gas, but you can smell the gas. And we have a mass spectrometer on both Philae and also the orbiter Rosetta. The one on Rosetta has picked up some fantastic stuff; sulphite compounds, rotten eggs, ammonia are stable so you can imagine what this comet smells like but we thought it would be best to provide a 'scratch and sniff' version for people to enjoy and there have been various reactions from 'it's not that bad' to the 'is it a perfume?' to a child was nearly vomiting on the monitor earlier on... so yes. It stinks basically!

Graihagh - Are you going to show me?

Matt - Yes...

Graihagh - I can smell something perfumed.

Matt - It's perfumy isn't it, yes? But, I mean, the thing is somebody's was saying it's got incense. This one's actually not as bad - maybe I'm used to it now! But, as I say, it's got hydrogen sulphide, ammonia, formaldehyde, methanol. We've also detected on the comet things like hydrogen cyanide but then you wouldn't want to put that on there because you'd sniff (04.23) and then pass out and and probably die.

Graihagh - Let give it another sniff...

Matt - Well somebody was saying incense as well.

Graihagh - it does smell a little bit like frankincense. What I'd imagine going into a meditation shop or something.

Matt - Some kind of hippie head shop, as they're known in the US. I still get mothballs so it still smells like 'a Nan' basically. The comet smells like 'a Nan' so I'll go generic.

Graihagh - So, other than getting a whiff of what 67P smells like, what's the best outcome here? I mean surely we're not going to unpick the entire origins of our universe and solar system?

Matt - Well, with Rosetta we are starting to do that. Really what we've got from Rosetta by spending the two years there by landing with Philae. And adding all of this stuff together, we're just starting to scratch on the surface of the capability of the data from this mission to the extent that we think we have identified primordial building blocks in the comet that are, actually, probably, common with other comets, that we can say we know how comets were made now. And that's quite a big result and the implications there lay in with the general solar system evolution

So that's what we have to look forward to. I wouldn't say we've solved everything but we've done a good job and there's a lot still to do and I'm pretty excited by the science that's going to come out in the next couple of years with Rosetta.

20:36 - How to find your own meteorite

How to find your own meteorite

with Dr Carolin Crawford, University of Cambridge

Top tips from astronomer Carolin Crawford on how to find your own hunk of  space metal after Graihagh Jackson found a rather intriguing question about a meteor falling into someone's wheelbarrow...

space metal after Graihagh Jackson found a rather intriguing question about a meteor falling into someone's wheelbarrow...

Question - Hello there, I was wondering if it is possible to test rocks to see if they are from space? I ask because, and this is true! Whilst I was gardening today a rock fell into my wheel barrow. It sounds crazy, but it did happen. The object is black, looks like coal, and is very light, I suppose like pumice. If It didn't fall from the sky, I would say it was a piece of normal earth rock, but as it came from above I'm very curious.

Giggles

Carolin - What did they say in response?

Graihagh - The response was something along the lines of - I doubt it very much because they're normally very heavy and that sort of thing. But it just tickles me. I read it and it tickled me to no end that these things were falling, and in these people's wheelbarrows or, you know, the idea of it falling in someone's wheelbarrow.

Carolin - A couple of years ago there was a lovely story of a French family who, as in the way of the French having their holidays, vacated their house in Paris, went off for their summer holiday and when they came they thought that's strange, our roof is leaking and they sent someone up to fix the roof. And what they found was the hole in the roof was created by a little meteorite that had just punched a hole through the tile and got embedded in their insulation in the roof. So they had their own little meteorite that had hit their roof - I think that's quite cool!

Graihagh - Yes, really cool, really cool! I imagine lots of people have got lots of interesting stories about how they've come into... I mean I was really excited about ours but I suppose it's not the most exciting way to come across a meteorite?

Carolin - No. The most exciting thing is when you actually the event. You see the fireball and a fireball is just when you've got a bigger lump of rock that, as it disintegrates, it produces a lot more light and often they would just break into lots of pieces and you'd just get a fantastic show as they fall to Earth.

Sometimes, if you're fortunate enough to see one of these, especially nowadays with security cameras and you get all these serendipitous sightings of the fireball, you can track it's orbit, you can track its path through the atmosphere, you can predict where it's going to land, and then people can go out and look for the bits of rock.

So, for example, this has been done in places like Canada where, across the country, people saw this fantastic fireball in the sky. And then, when it had landed, they tracked it down to where it had landed, they went out to look for it and, it being Canada, it's a land of lakes. All the lakes are frozen and you just looked at the lakes and there were just fragments of meteorites scattered all over the ice on these lakes. I mean that must be so exciting to see those.

Graihagh - I was going to ask, because you'd mentioned we're in the peak of this meteorite shower at the moment, is there any chance if I looked really, really hard that I might find one in the UK?

Carolin - I think it would be very, very long shot. No I don't think you've got much chance and you've got to remember that for this particular meteor shower Perseids the grains that are coming in they're tiny - they're not going to survive to Earth. You need a much more sizeable lump of rock to be able to get any fragments from it landing on Earth.

Comments

Add a comment