Thanks to Sannia Farrukh and the ICGEB for their support in making this show!

It’s thought that by the end of the decade, 78 million people around the world will have Alzheimer’s disease. It’s debilitating and progressive. It robs people of their personality, their independence, and their quality of life. And caring for people with the condition, which often goes on over many years, is extremely costly, both financially and emotionally. The biggest risk factor is age; and as the proportion of the population living into their 80s, when as many as a fifth of individuals can develop the condition, increases we’re going to see Alzheimer’s inflict a bigger and bigger disease burden on society. But are new treatments in the pipeline a ray of hope that we can meaningfully alter the course of the condition for those destined to develop it? Drug trials with the new agents donanemab and lecanemab suggest we can, and have been hailed as signalling the start of the fight back. That’s what we’re going to explore this week, including what’s behind the disease and its symptoms, the economics of treating it, new ways to diagnose it before the symptoms set in, and how these new drugs agents can help to turn the tide.

In this episode

00:52 - Caring for someone with Alzheimer's disease

Caring for someone with Alzheimer's disease

Chris Bane

What is it like to live with Alzheimer’s? Chris Bane speaks about his personal experience of looking after his mother, who has had Alzheimer’s for a few years now…

Chris Bane - I was living abroad when she was first diagnosed in 2016 at 67 years old, and I couldn't quite believe that mom had Alzheimer's. I thought 67, this is not a condition at that time that that affects someone so young. Mom herself doesn't think she's got Alzheimer's. She didn't at the time. She said, I seem to remember that's a disease for old biddies.

Chris Smith - What did you notice about your mum that first raised the red flag? That something might be up?

Chris Bane - One specific moment, actually, where we were visiting my brother who lived abroad, and she went upstairs to go and get something out of her bedroom and got lost. Couldn't find her way back downstairs. Mum, she did have a tendency to repeat herself, but that was a kind of light bulb moment of it's more than just, you know, repeating herself.

Chris Smith - And she still doesn't have insight into the fact that she has this condition because other people who have Alzheimer's, Terry Pratchett was quite frank and said, I've got this. And he knew he had that obviously he was much more vocal about it when it was early on in his diagnosis. Is she coming to realise that there's something wrong now or does she just forget?

Chris Bane - As she is right now? I honestly don't know what's going on inside her head. I'd love to know what she's thinking. She was a nurse all her life, so I'd imagine that she had some prior knowledge about Alzheimer's, and maybe, you know, in my thoughts, I'm thinking she didn't want to accept that because she knew that accepting it was actually quite a scary proposition because there was nothing you could do. I don't think there was any period in time where she's actually accepted it.

Chris Smith - How is she now? What sort of function does she have and what's your role in looking after her?

Chris Bane - I work full-time, so I also have a full-time live-in carer with mom now. She's lost all of her vocabulary essentially. I'm the only person who she remembers the name of, which I hold onto a lot. So, and that's those points, those little contacts where I'll give her a hug or stroke her, and she'll look at me and smile. I can still make her smile and that's the only quality of life she's still got. And that's the thing that's keeping me from putting her in a more formal care setting in a home, because we still have that connection. It's been difficult watching that because obviously mom was such a vibrant person and such a great mom.

Chris Smith - There are two sides to this equation, aren't there? In the sense that you've got the person who has the condition and in some cases they don't have much insight into what's happening. And then you've got the people who are trying to care for the person they care about and that obviously takes a huge toll emotionally, but also financially. So how are you coping with those sorts of challenges?

Chris Bane - I first started caring for mom in 2021 and started thinking about formal care. The average life expectancy, as I understand it for a person with Alzheimer's is 11 years, but it could be up to 20 years. And when you look at the basic care costs at that time, they've risen significantly in the last three years. We were looking at having to spend essentially a million pounds on care, which was such a frightening number.

Chris Smith - Is there a good support network out there to help people like you who are trying to remember to be a son, but also having to be a carer so that you can get some help, get some advice, and also get some time to decompress.

Chris Bane - The local GP has been great. Social prescribers have been really good and they understand mom's needs. Dementia UK, Alzheimer's Society, Alzheimer's Research, Age UK, they all have good information on their websites. There are local events, dementia choirs that happen. So there are but there's not enough. I've often equated sort of the experience of dementia to it's a disease or a condition that very much certainly from my experience, remains at home. If you were to get a diagnosis of a different disease, cancer, you would have that support. You'd say, okay, this is your treatment plan. You can do this, you can do that. With the dementia diagnosis, it's just literally one line on the GPS letter, I certify that Shirley Bain was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. That's it. They're very limited things that could be offered and it feels like it just stays at home behind the front door.

What is Alzheimer's disease?

Susan Kohlhaas, Alzheimer's Research UK

What is going on in the nervous system to cause Alzheimer’s Disease? Susan Kohlhaas is from the charity Alzheimer’s Research UK…

Susan - So Alzheimer's disease is a fairly common disease actually, and it's the most common cause of something called dementia. So the word dementia is used to describe a group of symptoms that include things like memory loss, confusion or difficulties with communication. And Alzheimer's disease is one thing that can cause dementia. Around six in every 10 people with dementia in the UK have Alzheimer's disease.

Chris - Who's most at risk?

Susan - There are a different number of factors associated with Alzheimer's disease. So there are people who are genetically at risk of dementia. And then around 40% of cases of Alzheimer's disease can be put down to what we would call modifiable risk factors. So things around lifestyle or environment that can influence somebody's risk of developing dementia. So we have things like air pollution, smoking, or diet that are influencing somebody's risk of developing Alzheimer's disease as well.

Chris - And because they live longer than men, on average, are women more at risk or if everyone reaches the same age as it roughly even stevens between men and women?

Susan - Interestingly, more women develop Alzheimer's disease and other diseases that cause dementia than men. And when they control for things like age, actually that doesn't explain the difference. So women do seem to be at greater risk of developing Alzheimer's disease than men, regardless of whether they live to longer ages or not. And we don't quite fully understand why that is.

Chris - But what is going on? If we look at the brain of someone with Alzheimer's disease, what do we see and why do we think we're seeing that?

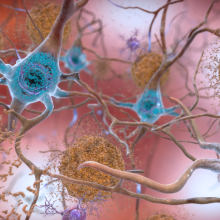

Susan - We see a lot of differences between the brain of somebody living with Alzheimer's disease and somebody without it. And I think one of the really important things to say is that Alzheimer's disease is not an inevitable part of ageing. You get people living to a hundred years old without any signs or symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. It's also one of these diseases where the brain changes start to happen kind of 15, 20 years before you actually see symptoms. So it's a really challenging disease to study for that reason. But what happens in the brain is that you get a buildup of certain types of proteins called amyloid that start to clump in the brain, and then that causes some further proteins such as proteins called tau to make tangles in the brain. And then that can cause a toxic environment for brain cells, and then they start to die. There's some more work to do that's looking at the role of things like immune cells in the brain and whether neuroinflammation can actually cause problems as well. So not only is there a buildup of proteins in the brain that are thought to be causing a toxic environment, there's also other mechanisms and cell types in the brain that seem to be going awry in Alzheimer's disease. And the challenge is to unpick all of that to develop new treatments.

Chris - These proteins that build up pathologically, what's their normal role then? Why are they there? Why do we have something that can become bad in some people?

Susan - So we don't really know exactly what happens to trigger the buildup of proteins like amyloid. There is some work to suggest that the role of these proteins when they're functioning normally throughout life can give some advantage to people. So the role of some of the genes that are associated with risk of Alzheimer's disease can actually be helpful in terms of navigation earlier on in life. There is still a lot more to learn in terms of the function of all of these proteins and what they do. What we do know is that in Alzheimer's disease, for some reason, they start to build up. And that could be because the immune system that's normally responsible for clearing proteins in the brain just isn't quite clearing them as quickly. Could be that there's something triggering that's happening that's causing this buildup. And there's a mixture, again, of environment and genetics that seems to be causing this.

Chris - If we look at how many people are affected by this now, and we look at the changing population demographics, what do we think the picture looks like in say, 30 years time?

Susan - At the moment, there are around 800,000 people who have Alzheimer's disease in the UK. But we think that this figure actually is probably an underestimate because many people, around a third of people living with dementia, never actually receive a diagnosis at all. And data on who gets diagnosed and where, is frustratingly just incomplete. So it makes understanding dementia and dementia care a huge blind spot for our healthcare decision makers and our wider politicians. We know that age and ageing is one of the top risk factors for developing Alzheimer's disease. And we also know that dementia in the UK is our biggest killer. So nearly 75,000 people died of dementia in 2022. So without any change, we expect the number of people with Alzheimer's disease to grow and we expect it to become much more costly to deal with the effects of dementia as well. So we really do need to do as much as we can now to find new treatments and ways to diagnose dementia better and also ways to prevent it.

Chris - And what are those effects? How would we recognize someone who's affected and what can we do better to support them?

Susan - The difficulty is that Alzheimer's disease and wider dementias affect everybody slightly differently because their brain diseases and the brain is such a dynamic organ and it's such a sort of key organ to anything that we do. So how we think, feel, behave, everything in Alzheimer's disease, you can start to see issues with navigation. You start to see memory and thinking problems that can crop up and then move away. You can start to see personality changes as well. And what we would always say at Alzheimer's Research UK is if you have any concerns about you or a loved one, please do go and see a GP in in the first instance because they can start to rule out things that it might be or also start to get you referred into a memory clinic in order to see whether you have Alzheimer's disease or other dementias, which would give you access to care and research that you wouldn't otherwise have.

12:43 - What is the economic cost of Alzheimer's disease?

What is the economic cost of Alzheimer's disease?

Ramon Luengo-Fernandez, Oxford University

Dementia is a significant public health issue throughout the world and will be one of the costliest health conditions to manage by the end of the decade. In 2021, treating Alzheimer’s disease in the UK alone cost 16 billion pounds. To explain how the economics stack up is Oxford University’s Ramon Luengo-Fernandez…

Ramon - So we've estimated, me and my team, the cost of dementia for 2018, taking into account healthcare costs such as NHS hospitals and drugs, social care costs, such as being in a nursing home, people coming to people with dementia homes to look after them, the cost of informal care ie spouses, children, family, other family, friends, and the cost of mortality - so early mortality, not being able to earn money or being part of the labour market or the cost of early retirement. So in 2018, we've estimated the course for dementia to be around 16 billion pounds.

Chris - It's a lot, isn't it?

Ramon - Yeah, it is a lot. Especially if you take into account the cost of institutionalisation into nursing and residential care homes and of course they're not direct where nobody pays their spouse who's taking care of their bowels with dementia. And these are the really big costs.

Chris - I suppose one way to make it more relevant or to give us a comparison is to think about other conditions which are fairly major causes of loss of life or ill health, and then look at what they cost. So if we take things like heart disease and stroke and so on, common things, how much do they cost us in comparison to a case of Alzheimer's disease?

Ramon - For heart disease, we estimated the cost in exactly the same way, looking at all the same costs, similar to dementia, so at 15 billion pounds, and for stroke it was 11 billion pounds. But the interesting thing is to see how the cost to distribute or who pays the cost. So for example, for heart disease, most of the costs are incurred by the NHS and also by people because heart disease is a disease of old age, it's more common to happen in working age than diseases such as dementia. So of course the early mortality costs will be higher than for dementia.

Chris - How do we anticipate that these costs, and particularly the dementia costs, are going to change with time? Because we're being told regularly we have an aging population, more people are living longer, and therefore they're living into the age regime where diseases like Alzheimer's become more common. So not only are we going to have more people who are at risk, we're going to get more cases and they're going to be around for longer, costing more money. So how do we expect this to change?

Ramon - So if we assume that nothing else changes, that the cost doesn't change, the number of people going into nursing homes doesn't change, and the amount of time people spend in hospital, if they're admitted, doesn't change. Just this projected ageing of the population will double cost. So if we expect the cost of dementia to be in 2018, about 17 billion pounds, then in 2050, we're projecting these costs due to population ageing alone to be around 34 billion costs. So a doubling of costs.

Chris - Is the impact not even more acute than that in the sense that if we think about where we were 50 years ago when things like the National Health Service were created and people were using old age pensions, the number of people who were in work productive in society and paying into the system to fund that was 10 or 20 people. For every person who was in the category of retiree or chronic ill health. And owing to the factors you've just been describing, we are now into an area where there might be as few as three workers for every consumer who's retired or in chronic ill health. And does that not mean that even the impact on society, it's not just as simple as saying the cost has doubled because the cost per person has presumably become even more acute?

Ramon - Yeah, absolutely. So in terms of society, the cost will be 30 billion. So we're doubling. It's to see who will pay these costs. So at the moment, the majority of the NHS, it's paid by the working age population through income tax and national insurance. Of course, if you've got less people paying income tax and national insurance, that means that there will be much more pressure if nothing else changes on these people. And you can't, some people would argue, keep taxing just to pay the NHS. So there might be ways on how we finance the NHS and more importantly for dementia, the social care system.

Chris - Although as you were saying that for some aspects of healthcare, the system pays, but for things like dementia, the burden often falls disproportionately on close family, et cetera, in order to almost make up a care gap.

Ramon - The big drivers of these conditions are social care and informal care i.e. people, your loved ones taking care of you. So of course social care, although a big chunk is paid by the state or local government, a huge other chunk is still paid by patients or their families. So it means that there might be an inequity in that if you've got dementia or stroke, you are more at risk of paying for your own care than if you have cancer or heart disease. And I don't think that's something that's being directly talked about.

Chris - Indeed. And what should politicians be saying, policy makers be thinking about them in terms of planning for this time bomb. I can't think of a better way of describing it than the time bomb that's ticking in our population.

Ramon - So from an economic argument, what you would say is you would want to invest to either mitigate these costs or to reduce them. And what's the biggest investment you can do in healthcare? One of the biggest investments is on research. So for example, we've been very good in cardiovascular disease in delaying the onset of you having a stroke or you having a heart attack. If you keep delaying the age of which you will have as a drug, probably you'll end up dying of other things. So of course it is dementia research, something that would probably generate a lot of good for each pound that the government invests.

20:19 - AI brain scans detect early Alzheimer's with 90% success

AI brain scans detect early Alzheimer's with 90% success

Tim Rittman, University of Cambridge

The best way to reduce the rising cost of Alzheimer’s disease is to heavily invest in research. And we think that one of the most critical targets in combating the condition is to find ways to diagnose the disease much earlier than we currently can to make treatments designed to slow or halt the progression as effective as possible. And that’s where Tim Rittman, at the University of Cambridge, comes in. He’s using artificial intelligence to detect the disease before symptoms set in...

Tim - There's one way we can try and get at that by looking at people who have say genetic dementias and we know we're going to get that in the future. So they'll have dementia passed down through the family and they carry a gene, which means they've got dementia later on. If we look at people in those groups, we can pick up subtle changes in the brain about 10 years before they develop symptoms. We can also look at the healthy population of people who go on to get dementia and we can pick up some subtle changes in their memory and thinking and general function about five to nine years before people develop symptoms or get a diagnosis.

Chris - How are you trying to do this?

Tim - So we've done this in a study called the UK Biobank and that's about half a million people across the country who volunteered to have tests and some of them had brain scans. So we took a computer algorithm which we'd trained to detect and sniff out Alzheimer's disease, if you like, by looking for these subtle changes in brain shrinkage. And we applied it to these, these healthy people who are around the age of 45 to 65, that sort of age group. So some of them might start to develop subtle signs of Alzheimer's disease. So we've got a big group of people who we know have Alzheimer's disease, so we can train our algorithm to sniff out Alzheimer's disease in those people that were confident about the diagnosis. And then we took it to this healthy group for about 40,000 people. We managed to pick up about 1300 who looked like they might have the start of Alzheimer's disease on their brain scan.

Chris - Can you not just use cognitive tests to find these people? Do we need to do additional, say brain scan testing on these people?

Tim - We have looked at the UK Biobank and those people who went on to get Alzheimer's disease. When you're looking at half a million people, we found these subtle changes in memory and thinking, but they were so tiny that you wouldn't be confident to say, well this person's definitely gonna go and get Alzheimer's disease just based on their cognitive test.

Chris - I suppose that's a reflection on the fact the brain is extremely good at compensating early on in the course of a lot of these degenerative diseases to overcome and surmount the problems that will later manifest.

Tim - Yeah, exactly that. Yeah. We know the brain changes the way it works and actually puts in a bit more effort early on to sort of cover up for the fact that there's early dementia going on.

Chris - Could we use this as a way to identify early people who might benefit from intervention either modifiable risk factors that we heard about earlier, smoking, drinking diet and so on, or also taking medications that might arrest the progression of Alzheimer's disease?

Tim - Yeah, I think it is. The study that we did was a sort of proof of concept, if you like to say, well this is possible to hunt out these people who might be at risk of future Alzheimer's disease. And I don't know if they're definitely going to get Alzheimer's disease, but they're certainly at high risk from it. So yeah, there's a lot of interest to try and pick out people like that for clinical trials to test out drugs that might stop or slow down Alzheimer's disease. I wouldn't be confident enough yet to say that these tests will definitely predict that someone's going to go and develop dementia. What we don't want is someone to have a brain scan and says, yep, you, you're going to get dementia because that will be the wrong message. But yeah, certainly finding people who are high risk, who might benefit most from those trials or interventions is really important.

Chris - I suppose one downside though is that we do need a brain scan, which is not a trivial thing to have for these patients. I recall David Cameron, former UK Prime Minister saying positive things about blood tests coming down the track. Is that an alternative?

Tim - Yeah, blood tests are definitely coming for, to support diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Probably in the next year or two we'll start to see them in memory clinics and yes, they'll certainly be easier. There's still a lot of question marks as to how accurate they are very early on. But more research is coming to try and increase their accuracy. But it might be that, you know, a combination of blood tests, brain scans and other tests might be the best approach in the end.

Chris - And what are the blood tests looking for? Because it's obvious with the brain scan, you're saying you can see subtle structural changes that are revolving in a person's brain, but what would a blood test detect?

Tim - So if you look at the brain of someone with Alzheimer's disease or another type of dementia under the microscope within the brain cells and around the brain cells, you see little clumps, little dots and those little dots and clumps are made up of these proteins. And the most sensitive blood tests so far are for a little protein called tau. And we've now got very sensitive assays which can pick up tiny, tiny, minuscule amounts of this tau, which has seeped into the bloodstream from the brain. And that seems to be the most sensitive test for Alzheimer's disease.

Chris - And in your view, if you were to take people whom you can identify with either blood tests or with brain scans as being at risk of Alzheimer's, what sort of a difference do you think we might be able to make to their outcome and to what sort of extent and over what sort of timescale? So how much earlier could we intervene and therefore what might be the overall benefit?

Tim - At the moment, you know, any answer to that is a guess. I think, we don't know, is the short answer, but I think we will be able to pick people up five to 10 years before they develop symptoms. That would be my hope. And if we can have a treatment which is safe and which is effective in those years, I think we could make a huge difference to people's lives. The challenge is that if we start treating people that early on, it's gonna take decades before we know the answers. But it's not just drug trial treatments either. It's also lifestyle interventions addressing things like smoking and blood pressure that we talked about earlier. So yeah, I think treatments and drugs are one thing and lifestyle and non-drug approaches might also be effective or part of the whole package.

26:39 - Has Alzheimer's treatment hit a turning point?

Has Alzheimer's treatment hit a turning point?

Will McEwan, Cambridge University’s UK Dementia Research Institute

The scans aiming to detact early signs of Alzheimer's disease look for amyloid and tau protein aggregates in the brain. But can we be sure that these proteins are the cause of the disease? William McEwan is a group leader at Cambridge University’s UK Dementia Research Institute…

Will - The best evidence is that people who have rare genetic forms of these diseases can have mutations in the genes that encode these aggregating proteins. So there's familial forms of Alzheimer's disease where there's mutations in the gene that encodes beta amyloid and these people develop early onset forms of Alzheimer's disease. And similarly for tau, people who have mutations in tau have familial forms of what we call tauopathies. They're not Alzheimer's disease because they don't also have the beta amyloid pathologies. But these observations were critical in really linking these protein pathologies to cognitive effects that we see.

Chris - And how do you think then, if we do believe, and that's pretty compelling evidence, isn't it, that they cause Alzheimer's disease. How do you think those proteins do that?

Will - The best framework that we have in Alzheimer's disease is that beta amyloid is a kind of trigger. So once that starts aggregating, it causes, and we don't really know how, it unleashes a cascade of events that ends up in neurodegeneration and tau pathology. So we don't really understand that, we think, from human genetics. So when we look at people who have Alzheimer's disease versus those who don't, we can pick up what are called genome wide association studies. So these are looking at across the genome, what are the genetic signatures behind Alzheimer's disease. It comes up with genes that are involved in inflammation. So we think that the immune system might have something to do with it and other cellular processes involved in handling fats in cells.

Chris - So that would argue then, and hence that explains why scientists believe that if we go after these proteins that are building up and we find a way to either stop them building up or dismantle these clumps, we have a chance of getting ahead of what is causing inflammation and therefore causing the disease to progress.

Will - That's exactly right. And the earlier we go, the better it's going to be.

Chris - And how are people trying to do that?

Will - The main approach at the moment, and it's recently been in the headlines, is using antibodies. So antibodies are molecules that your body makes to fight infections normally, but they're very good at sticking to things. So we can re-engineer them to stick to essentially whatever we like. People have re-engineered them to stick to beta amyloid and once they start sticking to the beta amyloid, your immune system then starts seeing that beta amyloid is a threat. So it starts then degrading it and clearing it. So these antibodies are delivered to people by an intravenous route and they make their way into the brain, they stick to the beta amyloid plaques and start causing their clearance. And over a few weeks of being treated with these antibodies, you can see in the brain scans that the amount of amyloid in their brain is substantially reduced.

Chris - That did appear also to map onto a clinical benefit, didn't it? Because of the people who got those infusions, it was reported that the disease slowed down in terms of how much worse the people were getting by about 30%. But you could say it was only 30%. Why do you think it was only 30%?

Will - That's a really good question and to be honest, we don't know the exact answer. It could be that it's too late. I mean, I think the main hypothesis is that when these people were treated, they already had symptoms and this beta amyloid cascade, if you will, had already been unleashed. So all we were doing was buying people a bit more time. So again, putting this emphasis on trying to diagnose people as early as possible so that we can intervene hopefully with a view that you might be able to extend that benefit.

Chris - What about side effects? Because there were some people who got quite dramatic as in the lethal side effects of doing this. Do we know why that happened and what we might be able to do to mitigate that?

Will - Yeah, so I think this is an inherent risk of antibodies. So antibodies have, they stimulate the immune system. That's what they're designed to do. In doing so, there is an inherent risk that they will overstimulate the immune system. Now, having shown that clearing beta amyloid is beneficial, if we can do this in another way that is not so aggressive, is not so stimulatory to the immune system, the path has been cleared to a new generation of drugs.

Chris - All of the emphasis so far though seems to have dwelled around beta amyloid. And you've mentioned it does have a partner in crime, tau. So are people going after other things other than just beta amyloid as well? And could it be that in fact the ideal therapy for Alzheimer's disease is going to focus on not just one thing but a whole raft of different targets. We give a sort of cocktail of treatments that hit the disease from a range of different directions.

Will - I mean my background is in virology actually. And that's been a very powerful approach certainly for viruses like HIV and also in cancer. So I think we can learn a lot from those fields. And my own research is looking at clearing tau. So tau occurs not only in Alzheimer's disease but also rarer dementias and neurodegenerative diseases. And actually, the amount of tau pathology that you have correlates much more closely with the amount of neurodegeneration suggesting it's much more closely related to the toxic effects of the pathological progression of Alzheimer's disease. So I think you are absolutely right. We do need to be looking at these other targets downstream of beta amyloid.

Chris - On the other hand though, it's only been in the last year or so that I think I've really had reason to be optimistic about this disease previously. I think we were very good at telling people they had it. We were very good at telling people why they were having problems. We were not very good at doing anything about it. And it seems we are on the verge of turning a corner.

Will - Yes, I think you're right. I think this really gives us hope. These are not the ideal drugs. These are not the drugs that will be prescribed in 20 or 30 years, but they will be the turning point. They'll be seen as the moment where we know that this is ultimately a treatable disease.

Comments

Add a comment