This week we go back thousands of years to meet our Neolithic ancestors, and discover how their innovations paved the way for all life as we know it.

In this episode

Who were the Neolithic?

with Eske Willerslev, University of Cambridge

Where did the Neolithic come from, and how do we know about them? Georgia Mills spoke to Professor Eske Willerslev from the University of Cambridge, who is a geneticist and evolution expert...

Eske - The Neolithic people seems to be a group of people who have invented agriculture, coming from the Middle East and Near East. Becoming farmers basically and they are moving up through Europe bringing that new lifestyle with them.

Georgia - Right. So they started in the Middle East and they spread across the world bringing their ideas with them, and they weren’t a separate species from us though?

Eske - No, no, no. It’s anatomically modern humans basically. But of course, they have different genetic composition than the hunter-gatherers that are living in Europe at the time when they’re entering and this is we can genetically observe their entrance into Europe.

Georgia - How do we understand their movements from their genetics?

Eske - Well, it’s because, as I say, they have different ancestry from the hunter-gatherers and, therefore, when you sequence the genomes of ancient individuals, you can see that some of them are completely different from the contemporary hunter-gatherers. And some are, you can say, mixtures between these hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers. So we can see, we can basically observe, genetically how they are moving across Europe, approximately at what time they are entering the different parts of Europe, and to what extent they have genetically influenced the local hunter-gatherers.

Georgia - They brought with them the advance of agriculture, what else made them special?

Eske - Well, I mean, they had both agriculture, they had domestic animals, and they were living in a different way. You can say that the society included more people than the typical hunter-gatherer groups, which were probably something like 20/25 people most of the year. So these, you can say, had real settlements. They also were non-mobile - they didn’t have a mobile lifestyle to the same extent as the hunter-gatherers.

So they had a very different, both way of life, but also a different food source, of course. The people in Europe that they were meeting were living from mainly hunting animals and fish, and berries and nuts and things like that. What you would call a typical paleo diet, I guess today. And these hunter-gatherers were basically living from something much more similar to present-day muesli and, therefore, we can see that this is a very drastic change in lifestyle.

I mean when we're going from hunter-gathering to farming it’s potentially the most severe change in lifestyle that we have undergone as humans. And we can see that the selection, even in the genome, in regard to things that are associated with diet. So, for example, these fat regions of the gene that are involved in transforming short-term fatty acids into long-term fatty acids. This is something we need these long-chain fatty acids for example for our brain and we’re getting them directly through meat and fish, but if you are eating bread and carbohydrates you basically need to change the short chain fatty acids into long chain fatty acids, and the fat regions of the genome is involved in that. And we can see that there has been selection on those parts, so it’s something that transition also affected us, not only in terms of that mixture with new people but it’s also affecting us biologically, if you want.

Georgia - And did this starting to live in these larger static settlements affect our susceptibility to disease as well?

Eske - Definitely. We don’t know yet whether these agriculturalists brought diseases with them. We have some suspicion that this might be the case, but it’s certain you can say, at least during that time, or slightly after that time where we start seeing the first epidemics, like plague epidemics for example. We see already in the Bronze Age, which is the period just following the agricultural arrival into Europe and so this change of lifestyle, of course, where you have more people together is creating the background for epidemic outbreaks such as plague.

Georgia - Why is it important to study them, to understand them?

Eske - In many ways, they are providing the fundament for the modern lifestyle that we see today. Many people would argue that the agricultural revolution in Europe is really creating the base for the creation of civilisations, and our civilisation today. Other people have argued, of course, that it’s the worst thing that happened to humans because with the new civilisation there’s also a lot of problems coming with this change in lifestyle. People have argued that our suffering from diabetes and other lifestyle diseases is really a result of the agricultural revolution and that we are, as a species, still trying to adapt to that change in lifestyle.

But however you’re looking at it, whether it was a positive or negative event, it’s certainly an event that changed the way we are both living as humans, it’s an event that changed our ancestry in Europe and it’s an event that also changed and affected our biology

07:06 - A day in the life of an archaeologist

A day in the life of an archaeologist

with Natalia Hanziac, University of Toronto

Is being an archaeologist anything like what we see in Indiana Jones? Georgia Mills joined Natalia Hanziac for a day in the life of an archaeologist. And forget a fedora and bullwhip, the tools of the trade are a little different...

Natalia - Our most important tool us our trowel. This is Slayer, you are welcome to wield her today

Georgia - So this is the trowel’s nickname; 'Slayer'?

Natalia - It is, yeah. We’ve been through some stuff together. She slayed some things for me. The second tool that we use quite a bit is a small pick, and that’s just to break up the soil, especially when we’re first starting to dig the hole. The thing that is very important to us is a brush. It’s important to be able to see what you’re digging because you’re moving dirt onto dirt, off dirt, looking at dirt. So it’s important to keep the old dirt off the new dirt and keep all your dirt separate.

We follow what’s called a probe and peel method. So what we do is we start in a small area of the square and bring it down until we find a change in the soil, some new architecture, something along those lines so we’re not digging blind across a 5 by 5-metre space, just maybe a 10 centimetre by 2-metre space. Once we find some of that information we then extend that small hole we’ve made across the whole square.

Georgia - Because soils build up over the millennia, each layer of soil represents a different point in time. So this probe and peel method excavates a bit by bit so you don’t miss anything. But it’s certainly not easy…

Oh, this hurts your legs.

Natalia - A little bit. The ankles too, and the knees, and the back.

Georgia - And for long periods, you don’t find anything, except for the occasional rock…

Natalia - The eternal “is it a rock? Is it an artefact?” question, it looms over us all.

Georgia - Or the odd creepy crawly. There’s a big old ant on the brick.

Walter - That’s fine.

Georgia - Do they bite?

Walter - Ah, maybe. But I’m bigger than it.

Georgia - But every now and then...

Walter - Oh wow. Look at that. Now that is a huge one! Look at that - beautiful.

Georgia - You hit the jackpot – be it tool, bone or pot, and then you extract it.

Natalia - Very carefully.

Georgia - And it’s all tagged and bagged.

Natalia - For its long trip through science

Georgia - And as well as the artefacts, in a site like this you’d also keep a lookout for big bits of charcoal.

Natalia - Yeah. So these are all some sort of carbonised wood, which is awesome because it tells us that there was definitely burning here. But it is also what we hinge our carbon dates on, which is how we put the site in an absolute time. So a lot of the artefacts, just through their characteristics will tell us that they are Neolithic based on where they're on the ground but also how they relate to other sites in the area. But a really big question with the excavation here at Gadarchilli and over at Shulaveri, is where does this actually fit on like a real timescale. How far back are we talking about when we say origins of wine? People using hides, possibly domesticated dogs like what does that actually mean?

Georgia - And the buckets and buckets of soil that are removed are sampled and sifted, to collect any small pieces that might have escaped you. All the while, as you go, you record, draw and photograph everything you can.

Natalia - Every single time we move even just like a speck of dirt we’re technically destroying something that has sat in place for anywhere from 10,000 years to a couple of months, but we are very much disturbing everything that we touch. So it’s very very important for us to make sure that we maintain meticulous notes because as soon as it’s gone it’s completely gone.

Georgia - At the end of the day they even take a photo of the whole site using a drone. Apparently, in pre-drone days they tried everything from kites to selfie sticks to get this bit done. And after many hard hours of graft, it’s back to HQ. There the students started drawing and labelling and sorting their finds, ready to go into the lab for analysis, all under the watchful eye of project mascot, Lulu. Others go out on a survey, walking over wilderness looking for anything that might indicate an interesting place to dig in future, all the while avoiding the local snakes – which I am told are liable to coil up and spring at you, like terrifying slinkies. I don’t know whether to believe this. And once again, finding genuine artefacts is pretty rare. I uncovered some soviet metal, one livid scorpion and, you guessed it – more rocks.

Steve- What we charitably call an interesting rock.

Steve - In Turkish we say a"güzel taş": a pretty stone, but just a stone.

Georgia - Why didn’t they make their tools more obvious and write their names on them?

Then it’s back to base, time for a quick dinner, and off to bed ready for another 5am start. Trying to get a good night’s kip through the thunderstorms that are loud enough to shake your bones, and the odd earthquake.

So apart from the snakes, only a passing resemblance to Indiana Jones

Natalia - That movie really set up false expectations for me.

13:25 - Life in the year 8,000 BC

Life in the year 8,000 BC

with Steve Batuic & Walter Mancini, University of Toronto

What would village life have been like 10 000 years ago? Georgia Mills spoke to Steve Batuic and Walter Mancini to find out...

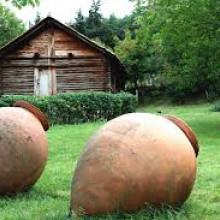

Steve - This is your standard Shulaveri-Shomu village. So what you have is a series of circular structures, varying in size from 1 metre to well, our largest one is close to 7 metres. Their clustered together, sometimes you have buildings that are clustered in a figure eight pattern like these two large ones over here. So you’ll have the figure eight pattern or you’ll have them nearby and you'll also see sort of circular balls that will join them as well. And they’ll form small clusters, almost like a household area where you’ll have a couple of structures and an enclosed courtyard if you will.

That’s sort of the general pattern that you see and what you’re looking at too in these squares is you can see that some of them are different levels. You’re looking at different phases of construction. So the lowest one would have been built first and then later they build that add on and add on over time. These families of people would have been expanding over time.

Georgia - And what were the houses themselves made out of?

What we’re doing now is taking a sample of a mud brick from the lower level of the site so that these French mud brick experts can analyse it and tell us something about them.

Georgia - Right. And mud brick is what the people who lived here were building everything out of it looks like.

Water - Yeah. They are clay mud brick and there are sunbaked. As you can see the inclusions here inside the clay, this is definitely mud brick. And all these little holes you can see here, are pretty much decayed organic material like plants which are found in the clay. Mixed together with the clay to compact the mud brick, and make it more solid.

Georgia - As well as plant material like wheat, the mud bricks were mixed together with poo, and occasionally bone to make them stronger. It may not sound like the most enticing thing to build your house from, but the Neolithic knew what they were doing – these things could last.

And what’s this giant - I’ve been wondering about this, it looks like an anthill, just slightly taller than me behind me, what is this?

Walter - This is one of the earliest structures that we have on the site, and it’s one of the most well-preserved. And what we did last year was to build a sort of cover with clay but, unfortunately, it collapsed at the beginning of this year. So maybe we didn’t get the right amount of clay or the right proportions.

Georgia - So the 10,000-year-old structure stood up and the one you guys made fell down in a year. So a new-found respect for the Neolithic.

Walter - For sure.

Georgia - And I’ve got to say I’ve been on the lookout for a good Indiana Jones hat. I haven’t seen any yet but yours is closest so I’ve got to congratulate your hat game.

Walter - Oh thank you so much. I’m Italian so fashion is first concern.

Georgia - Fashion icon Walter Mancini there.

So they had these sturdy houses, but what was life like in a Neolithic village? Back to Steve.

Steve - Well, it would have been pretty tight clustered houses, so people would have been pretty much on top of each other and, as you can see, the houses aren’t that large. They would not be doing a lot of their activities inside, they would have been doing them outside especially in those courtyard areas around the houses. You would have had agricultural fields that would have been immediately around and it also seems that they would have had vineyards around here as well.

What the Georgians have done - we have an excellent palynologist who works at the Georgian National Museum where she’s been collecting soil samples from either outside in the courtyards or inside the buildings, and she’s been able to actually find grape pollen; in fact well vine pollens essentially. And she’s also done other studies with modern vineyards and realised that grape pollen doesn’t go very far, so for it to be in these houses means the vineyards had been either close or they’re collecting the flowers and bringing them nearby. So there probably were vineyards in the immediate vicinity. And then couple that with the motif of the grapes, this has sort of led to the idea that they were probably drinking wine in here as well. So it would have been a simple agricultural village growing wheat, barley, other legumes, but also undertaking horticultural practices.

Georgia - This evidence for viticulture and wine is what makes these sites so important. Last year they found a pot with the residue containing a combination of acids which indicates wine, which have been dated to around 8,000 years ago which pushed the date back for the earliest winemaking by around a thousand years.

And that’s not all…

Steve - Viticulture, growing vineyards would have been the main things and then also it now seems, based on some of the new evidence that we have, apiculture as well. Basically, they would have been caring for bees if you will.

Georgia - Oh wow!

Steve - This is one of the things that we’re presently working on as we also have the earliest evidence for honey.

Georgia - What form does that take?

Steve - It’s the same person, our pollen specialist. She was looking at a sample that comes from the site of Shuliveti where we’re also working. Basically, it’s a trash pit from a hearth and so somebody had been cooking and then cleaning out all the ash and everything like that. And so she was looking at it and the sample that she had had this incredible - well this clustering of pollen of a very diverse variety of basically meadow plants, and also arboreal flowers.

According to pollen specialists, this is the signature of honey because… I should also add that they were also insect legs, like honey legs that were still caught in this as well. You would not have such a diverse collection of pollen like that if it’s an anthropogenic thing because we can’t collect that. We wouldn’t normally collect that diverse of pollen or flowers, if you will. But bees are going from flower to flower all across the place within a 7-kilometre range. They can collect that great variety and that’s what’s represented, that’s the signature, if you will, of honey having that great variety of pollen.

Georgia - Right. So they didn’t have much space to move around in but they had wine and they had honey, so life might have been quite good?

Steve - It wouldn’t have been that bad, I imagine.

Georgia - Is the site one sort of singular settlement over time or is it several?

Steve - Well, this is actually one of the interesting things that we have started to understand just really sort of this year. What you do have, if you look across the landscape, you have our mound, you can see another mound over there. That is the site of Imiris-Gora; it was also excavated in the 1960s. Then off over there 2 kilometres away is the eponymous site of Shulaveri-Gora, which had been excavated in the 1960s by the Georgians. And what you seem to be looking at is a cluster of sites but they’re all occupied at different time periods over the thousand years of Shulaveri-Shomu culture.

The invention of farming

with Howard Griffiths, University of Cambridge

How did the Neolithic invent farming, and how has it changed since then? Georgia Mills spoke to Cambridge University's Howard Griffiths...

Howard - So when farmers crop land for too long you tend to get that one crop uses similar amounts of nutrients year on year, so you tend to get progressive impoverishment of the soil, and also you tend to get a buildup of pathogens. So the two things tend to mean that progressively yields tend to decline with time.

Georgia - Right. So if I’m having a field of wheat that I wanted to run through year after year, the wheat would eat the same nutrients again and again out of this soil that wouldn’t have any way of replenishing them, and the same diseases that like the wheat as well would be building up year on year?

Howard - Yeah. And it’s exactly what we see in East Anglia here where we have a take-all which progressively reduces wheat yields and that’s why we have to rotate crops.

Georgia - So what’s crop rotation?

Howard - Well basically it means that, under the current example, you grow a single crop perhaps for two years at most before switching to another crop to allow the soil to recover.

Georgia - How does the soil get its nutrients back?

Howard - Well, two ways really. One is that the increased weathering brings in more nutrients from the bedrock and that is, of course, helped by the roots which actually help to digest some of the rocks where the acid water’s going down though. Otherwise through fertilisers that come in. Some naturally as a result of lightning bringing in nitrogen. Others, of course, through manures and that’s where progressively early man probably would have learnt fairly quickly that some form of manuring would aid crop productivity.

Georgia - And so if you replace wheat with something else then also the bacteria or whatever it was that was feasting on the wheat would have nothing to eat and, hopefully, disappear as well?

Howard - Yes, that’s the general idea. Yeah, it just gives a break and so then the land is healthier and more nutrient-rich ready for the crop when you replant it.

Georgia - How long does it take for soil to recover between wheats?

Howard - Well, as I say, currently I think it’s in the region of about a year or so, or a year or two following intensive cropping. Although I believe in the East of England there are some farmers that are able to get through this rather impoverished time and can grow wheat continuously, but it tends to result in lower yields.

Georgia - And this is exactly why the archeologists think the settlements were moving around the landscape. They had only just started to farm so hadn’t hit upon this idea of crop rotation, but they were finding their yields were less and less each year. So after using up all the land around the settlement, it was time to move on. But what kind of things where they farming? Back to Howard…

Howard - Okay. Well, the early evidence suggests that we started to select early wheat varieties. There’s one variety called Einkorn which, as it sounds, it just has a single grain in its ear.

Georgia - Wheat’s quite surprising because if you look at wheat and I guess you don’t realise you can turn it into tasty, tasty bread and pasta. It doesn’t look sort of immediately useful. I’d much rather something I can eat straight away.

Howard - Well, like all of these things, one wonders how much of this was found by accident in conjunction with leaving grains near the fire and so on. But we do know that the early Neolithic man had breads and had found ways of grinding grains to make flour. So it rapidly became adopted I think as a staple diet. We have wheat and barley were early domesticates, but also things like poppy and flax, and some legumes as well so lentils and vetches and so on. Those were the earliest crops.

Georgia - How have those crops themselves been changed by our repeated farming of them? Would they be recognisable I suppose?

Howard - That’s an interesting question. So the extent as to whether the seeds have actually increased. What we certainly have managed to do is select grains with increasing yields but, at the same time, we’ve been able to build on a number of chance hybridisations whereby two grasses accidentally merge their genetics - genetic bases - and that led to this hybrid effect with increased yield. And that has ultimately led us with the characteristic wheat ear that we now recognise; whereas if you saw one of those early wheats you’d scarcely recognise it as a crop that we’d recognise as wheat today.

Georgia - In terms of the farming itself, how’s that developed in the last 10,000 years? I imagine quite a bit.

Howard - Well, indeed. There’s a lot of debate in the UK about the extent that the forests were initially cleared in what’s the Stone Age. But I think, in the UK certainly, we think that the chalk was cleared first, which would have been the uplands because it’s the lighter soil so it’s easier to plough with early stick ploughs and so on, and that would have been cultivated initially. The argument goes that it was only later, about 1,000 years BC or so, that the iron-shod plough came in from Belgium and so on, and that then led to the heavier clays being tilled.

Georgia - What is tilling?

Howard - Basically, it’s a question of having cleared the basic forest. It’s then a question of creating a seed bed because what growing crops is all about is creating a monoculture. And in fact, funnily enough, some of the earliest Neolithic sites have seeds of weeds very characteristic as well, so sort of speedwells that we characteristically find in our flowerbeds and so on today. Presumably, they were weeds that were growing amongst the crops, the barley and wheat, that was being cultivated by those earliest farmers.

27:03 - All hail obsidian!

All hail obsidian!

with Shaun Doyle, Flint knapper

Obsidian was used by the Neolithic in volcanic areas of the world and is still one of the sharpest materials we can make today. Georgia Mills got her neolithic on with flint knapper in residence, Sean Doyle.

Sean - Knapping is the general term used for the production of chipped stone tools but generally, it is the tools that are made with siliceous material.

Georgia - Siliceous?

Sean - It is a very siliceous rock actually. Obsidian has a very high silica content. Siliceous stone is a stone where its main component is silica.

Georgia- Right. And obsidian is the thing that earlier in the dig, we found lots of tools made of Obsidian, and you’ve got a massive rock of it here and it’s dark and black, and shiny, and very beautiful. And I also know this is the thing that in Game of Thrones they’re very excited about, they call it Dragonglass. So this is, to me, quite a mystical object but what actually is it?

Sean - First of all, I’m a big Game of Thrones fans so I love me some dragonglass, and if I can kill a White Walker one day I totally would. In our world, obsidian is a stone that’s formed in volcanic eruptions. You need a lava that has a really low viscosity, which means it’s very fluid and liquid, and it super-cools very quickly, so quickly that the elements inside don’t have time to crystalise, so you end up with a very homogenous natural glass material. The crystallisation process, kind of, ruins its predictability. So the more glass-like it is, the more predictable it is, and the more easily you can flake it into the tools that you want. Other siliceous stones are flint and various types of chert-like chalcedony or opal or some quartz.

Georgia - Take me through knapping then. How would I go about turning this big block into a nice little knife?

Sean - Basically you just stare at your stone a lot until it speaks to you.

Georgia - Oh wow! That’s very scientific then?

Sean - Yeah. That’s the easy way to put it. But really it depends on what you're trying to do with the stone. If you’re just trying to take a flake that you can use to cut something with, you’re just looking for an angle that’s under 90 degrees; this one here’s about 70. And you’re just looking for a flat strong platform that you can hit with the stone that will withstand the strike, and allow the shockwave to travel through the piece, kinda like this...

Crack crack

Georgia - Eureka. That’s a really nice one.

Sean - So that’s a nice thick flake. You know it’s such a versatile material that you can pretty much shape it into anything you want once you know what you’re doing.

Georgia - Once you know what you’re doing, being the operative phrase here. That didn’t stop me from demanding a go. And I don’t know why you’d have large chunks of obsidian lying around your house, but please don’t try this at home. I found out it’s very easy to cut yourself.

Sean - I have a few scars from my learning days. But every scar is a lesson, that’s what I always say.

Georgia - So the rock speaks to me, yeah?

Crack crack crack

Sean - There you go.

Georgia - Oh no! I didn’t do a nice flake like yours. I just cut off the end.

Sean - Yeah. Well, it exploded a little bit but that’s part of the learning process.

Georgia - Okay. What did I do wrong?

Sean - A couple of things.

Georgia - So we mentioned Game of Thrones earlier, could you make a sword out of this stuff? Would it work?

Sean - Well, I could make a sword but it probably wouldn’t be the most practical thing. It would probably break in half the first time you tried to hit something with it.

Georgia - Brittle it may be, but what it lacks in sturdiness it makes up for in its edge, which I would say was razor sharp but really it makes a razor look like a crayon…

Sean - Yeah. Obsidian is so sharp, a sharp edge can be something like two nanometres in thickness, or something like that, so it gets so thin that you can cut between blood cells. Actually, obsidian is still used in some modern surgeries for that reason, but also because you can sterilise it really easily. It doesn’t have the same pores as surgical or modern steel does so you can sterilise really easily.

Georgia - Do we think the Neolithic people were using it for surgery?

Sean - You know what, they probably might have been. They used it for all sorts of different things including scarification, bloodletting, maybe tattooing even. Yeah, it’s a very versatile material. They even made mirrors with it.

Georgia - It is very shiny!

Sean - The first mirrors in the world were made from obsidian.

Georgia - You’ll be pleased to know none of the team used it to do any bloodletting, but one Georgian archaeologist, Dima, did actually manage to shave his beard with a blade. Again, please don’t try this at home.

But obsidian, as well as giving insights into how the Neolithic lived can also tell us a bit about their movements.

Sean - Each obsidian source is unique in its chemical signature actually, that’s why it’s used very effectively in sourcing. So we can use various lab instruments like X-ray diffraction and others to identify its trace elements so that you can match artefacts in the archaeological record to the obsidian source that it came from.

Georgia - Right. So if people were trading with this you’d know how far it had moved?

Sean - That’s right, yeah. And because it’s such a homogenous material it’s much easier to do that than with say flint or chert, so you can tell exactly how far material was travelling in the past.

Georgia - All hail obsidian then?

Sean - All hail obsidian. It’s my favourite thing in the world.

Georgia - Me too now, I’ve decided.

Sean - Perfect.

34:44 - Old bones and new experiments

Old bones and new experiments

with Steve Rhodes, University of Toronto

What secrets do the various animal bones on a neolithc dig site impart? Georgia Mills spoke to GRAPE Project zoo-archaeologist Steve Rhodes...

Steve - I study animal bones and essentially human subsistence based on that.

Georgia - Awesome. We’re in the lab now; it’s lots of boxes of various things and there’s a lot of bones. So what kind of things have people been finding?

Steve - Well predominantly, in terms of food animals there are a lot of caprines mostly, sheep, a few goats, a lot of pigs, a lot of cows. And then we also have wild versions as well as domesticated. So we have domesticated sheep and goat but it looks like we have some wild - found a very large horn core of what looks like a wild goat. And we also seem to have wild aurochs which are wild oxen, the progenitors of domestic cattle; very much larger, and even possibly bison, which were native here many years ago.

Some of the other interesting things we have are very large catfish. The Wels Catfish is the common name, and they can get up to 2 or 3 metres long. And we have these bead objects here that were made from them that we’re kind of curious about whether they were decorative beads, or possibly ear spools, or it’s even been suggested they might have been spindle whorls for making fibres from wool or flax.

Georgia - Oh right. So it’s kind of like a little bone doughnut kind of thing. This is from a catfish?

Steve - Yeah. That’s our best guess right now is catfish. It looks the most like that.

Georgia - Right. So these guys were having a lot of animals to eat, and animals like the catfish, which maybe have been used in some kind of art or decoration, and then what else were they using animals for?

Steve - A huge amount of their technology, like their tool kit was made from animal bone, and it’s more so than in other areas that I’ve worked like in the lavant where they have flint, and they make a lot of tools out of flint. But here in Eastern Georgia there’s almost no flint and it’s all obsidian, which is great for making some things, but it’s not great for others because it’s so fragile so making a lot of tools out of it is problematic; for example, we don’t see any obsidian arrowheads. And what I was thinking was that maybe it’s because when they hit the animal they shatter inside it and fill your potential meal with lots of shards of tiny little glass, so the people probably figured that out really quickly. And what they do have are bone arrowheads which are quite uncommon in other places but seem to be typical here.

They also seem to have been doing a lot of hide processing, so we have a huge number of awls like piercing tools that were made. They seem to have had a real consistent technique. So they have this really standardised hide production industry. It looks like a cross through this whole culture that’s quite interesting.

Georgia - What would hides have been used for?

Steve - Predominantly clothing I would assume, at this point, because it doesn’t seem like they were doing any weaving because we don’t have really much evidence of that, and this would be a little early for that. They were probably using it for containers a lot for carrying water and things like that or just general transportation of goods.

Steve - Could a hide survive that long? Could we ever uncover one?

Steve - Theoretically, in this environment it’s not likely. They have been found in places like bog deposits in Northern Europe like Denmark, Ireland, places like that. Or mummified in places like Egypt or high altitude sites in South America and places like that. But that’s a very different environment than what we have so it’s highly unlikely we ever find that here.

Georgia - Not content to merely look at these bones, at the GRAPE project they really wanted to get inside the minds of the Neolithic…

Steve - And when you tear the skin back…

So tear at it?

Steve - Yeah. Then you’ll have to go around the outside and just cut the top.

Georgia - There’s a table covered in tiny sheep legs. There’s a lot of students covered in blood.

Steve - I wouldn’t say covered in blood.

Georgia - What on earth is going on?!

Steve - We are replicating some of the bone tools that we’re finding at the sites at Gadachrili and Shulavaris that we’re excavating. It’s part of the learning process; we’re trying to learn how Neolithic people made their tools.

Georgia - Right. And so you're using an obsidian blade to do what exactly?

Steve - The sheep legs came with the skin on so first we have to remove the skin and the viscera and then we have to disarticulate the metapodials from the phalanges from the toes. We’re not using the toes, were just using this part here. And then, after we’ve done this we’re going to start breaking the bones because we have to break these bone in half in order to replicate the tools here. So after we’ve got all the viscera off, we’re going to be scoring them with a stone tool to guide the fracture when we break it, and then breaking them open with stones with like a hammer and anvil type technique, and then finishing shaping them with other obsidian blades.

Georgia - Right. Gory work then?

Steve - I guess in one sense. But you know if you’re a Neolithic person this would be nothing to you because you’re used to living in the natural world. There were no butchers shops, no restaurants, you did everything yourself.

41:02 - Wine making in Georgia

Wine making in Georgia

with Aleksander Chkhaidze, KTW

How did the invention of winemaking affect how wine is created in Georgia today? Georgia Mills found out about the current way of making (and drinking) wine from Aleksander Chkhaidze, managing director of KTW Group, on of Georgia's largest wine manufacturers.

Aleksander - We’re an interesting country in terms of winemaking because not only do we do wine by traditional way of European way, but we also do our own traditional way which is making wine in qvevris, which are a clay vessel, huge ones starting maybe from 5 litres going up to a couple of thousand litres. We handpick the grapes, and after handpicking our grapes we transfer it to our marani where we have kvevries.

Georgia - What’s a “Moroni”?

Aleksander - Marani is a wine cellar in Georgia. A very widespread and nationally treasured word for us.

Georgia - Oh! Marani not moroni!

Aleksander - Marani not moroni.

Georgia - And do you have a marani here?

Aleksander - Yes, I can walk you through.

Georgia - Can we have a look?

Aleksander - Yes, sure.

Georgia - Fantastic. It’s a beautiful building. Massive church appearance. Wow, and it’s just opened up into this massive cellar full of wine bottles. It’s a lot of wine you’ve got here. What are these traps in the ground? They look like they’re designed for people to fall down.

Aleksander - Those traps, we call them qvevris.

Georgia - Oh, these are qvevris?

Aleksander - Yes, they are.

Georgia - I’m going to stick my head in one. They’re - oh my gosh - they’re huge. There’s some excellent reverb in there. So you can probably tell from the sound just how big these are. And they are being kept underground for, I guess, you put all the grapes in there and then seal it up?

Aleksander - Yep.

Georgia - And so putting wine in a qvevri that’s quite a different method to the rest of the world so what impact does that have on a flavour?

Aleksander - Oh, it gives us stronger flavour then the regular method of making wine. But qvevri is so different that I’ve never heard an instance where somebody tried qvevri and said oh, that reminds me of something because it’s so different. It gives it a clay-like flavour which is weird because we don’t eat clay but at least we have smelled it. We have experienced it. And there is a saying that we use in Georgia that “clay makes wine better.”

Georgia - And almost as important as the wine making traditions are the wine drinking traditions!

Aleksander - Our Sucra, which is a feast is a very interesting phenomenon. It’s led by a guy named Tamada who people choose before the feast.

Georgia - So the Tamada is someone who sort of leads the table.

Aleksander - Yeah. He leads the table by saying the toasts.When he says a toast, everybody has to say that toast. Maybe they can just say "gaumarjos", which is cheers, but they can also add something. And usually when we drink, tamada says something and then all of us just say something about that toast. It’s not only a drinking process, the process goes into communication and you become close to each other after Georgian feast because you open up about many things and you talk about different stuff. It’s not just like cheers, cheers, cheers and drink. And sometimes we have a thing called a “Different”, when we introduce some weird stuff to drink out of. It can sometimes be a huge clay jar or a vase, or, I don’t know, some people drink out of a guitar as well, or a shoe sometimes. We don’t do that kind of stuff mostly, just something drinkable, you know, a vase or a huge glass or to like add a new flavour to the feast.

Georgia - A new flavour, especially if it’s from a shoe.

Aleksander - Yeah, I don’t like drinking from a shoe.

45:23 - Why dig up the past?

Why dig up the past?

with Natalia Hanziac, University of Toronto & Eske Willerslev, University of Cambridge

What's the point of investigating the neolithic? Georgia Mills heard from Natalia Hanziac, from the University of Toronto and Eske Willerslev from the University of Cambridge...

Natalia - As you get more into asking questions of the past you realise that you’re really asking the questions that are important to us today. So the questions that we’re asking might not even be relevant to people who lived 10,000 years ago. It might not be something they think about, but it’s the fact that we’re thinking about today tells us a lot about what it is to be a person in the 21st century.

Archaeology is fundamentally figuring out where humans came from and why we are the way we are today. So the materials that we look at, especially if things like ceramics and plaster, we’re investigating the first times humans made synthetic material. And synthetic material is a bit part of our existence today. But furthermore, things like ceramic and like obsidian are still used as components in tools we use today, which is very cool.

Georgia - When you’re looking at things from thousands of years ago do you feel a kind of connection with the past?

Natalia - Absolutely. Pulling something out of the ground that hasn’t been touched in 10,000 years gives you a really close and intimate connection with the last person who touched it. You might not know who that person is but it’s a kind of connection through time and a little bit through space between yourself and essentially people who came before that made us who we are today.

Georgia - I’ve been here for just under a week. I haven’t been getting up as early as you guys - a 5 am start, backbreaking labour. What keeps you doing it because it’s not easy is it?

Natalia - No, it’s not an easy pursuit but it is one that is incredibly rewarding. And part of it is that we work with people to get the work done so you’re forging human connections with people who you wouldn’t necessarily work with daily. We are very very lucky to work with incredible Georgian students for instance. But also the experience of pulling something out of the ground and really revealing parts of the puzzle that you might or might not be able to put together in a coherent way. It’s sort of like catnip, it’ll just keep you going and keep you coming back for more.

Georgia - Kind of like gambling?

Natalia - A little bit like gambling.

Georgia - So how different are we from our neolithic ancestors. Back to Cambridge University’s Eske Willerslev…

Eske - There has been some evidence suggesting the hunter-gatherers originally came into Europe. Their appearance was quite different from today. They had much darker skin, they had blue or grey eyes so they would have looked different from present day Europeans. They would have language but it would have been the hunter-gatherer language which would most likely be very different from the language we are speaking today, because the inter-European language is first really coming into Europe during the early Bronze Age with the Yamnaya expansion.

Georgia - You say they brought in all these innovations but we know these days we know about farming, we have all this scientific reasoning behind this, but they wouldn’t have known any of this. So how did they make so many innovations?

Eske - What made the farmers so successful is that for some reason they must have had more children that survived basically. So the population growth of the farmers seems to have been larger than among the hunter-gatherers. And it’s kind of ironic in the sense that if you look at the health state of the farmers it actually looks like the health state is poorer among the farmers than it is among the hunter-gatherers.

So you can say in some ways it was probably a less good life if you want. I mean that’s how it looks at least from the skeletons. They have teeth problems, they are fairly small,their backs are kind of affected by the line of lifestyle. Their nutrient state is not as good as the hunter-gatherers but they still seem, you can say in terms of numbers, more successful than the hunter-gatherers.

Georgia - The innovations they made like, for example, that if you leave grapes out for a while it makes wine, would this have been intentional or accidental do you think?

Eske - Well, it’s a good question. It’s not very clear exactly how the domestication happened. I mean where you start nourishing little bits of wild crops and turning them into domestic over a long period and it’s something that happens fairly slowly. Others have argued that it’s much more focused, and I don’t think that’s really resolved. But of course when they’re getting into Europe, to some extent they mastered this new way of life at least to an extent where you can say it’s successful and they made possible the spread of that lifestyle.

Related Content

- Previous Fear on the Brain

- Next English youths drinking less alcohol

Comments

Add a comment