Norovirus, the winter vomiting bug, affects 1 million people each year in the UK. But what is it, and how can you best protect yourself? Plus, in the news, how stress hormones depress the stock market, brain training that can improve vision on the baseball field, a new biological marker to diagnose those at risk of depression and artificial growth factors to speed up wound healing...

In this episode

01:18 - Stressing over the financial market

Stressing over the financial market

with John Coates, Judge Buisness School

This week, Cambridge scientists discovered that chronic stress makes people much less  likely to take risks which could have a depressing effect on the stock market. Chris Smith was joined by John Coates from the Judge Business School to find out more...

likely to take risks which could have a depressing effect on the stock market. Chris Smith was joined by John Coates from the Judge Business School to find out more...

Chris - Why were you doing this?

John - Well, I'm a former trader myself. I worked on Wall Street for about 13 years and I really had a strong hunch while working there during some periods of financial turmoil that the bodies of traders were playing a far bigger role in the decisions they made than economics and finance had really appreciated. So, there's this belief in finance and economics that financial decision making is a purely cognitive activity, I don't think it is. I think risk taking involves our entire body and brain working together. So, we're looking at the way, things like stress hormones affect financial risk taking.

Chris - When you first began looking at this, it was actually the time of the global financial crisis in 2007 -2008. You said that perhaps stress may have a long term dampening effect on markets. Is that what you were exploring in this new publication?

John - Yeah. We've been doing a series of studies. We're trying to combine field work with lab work, which is a spectrum of studies that you get in mature biological science. You don't find that so much in economics. But in the field work we've been conducting on trading floors in the city of London where we've been sampling stress hormones from traders, we found in one of these studies that when the volatility went up in the market, in other words, uncertainty went up in the market, stress hormones followed it almost tick for tick. In one of these studies, stress hormones in the trading floor was 68% over a 2-week period as the volatility of the market increased. We sort of asked ourselves, me and my colleagues in the department of medicine at Cambridge said 68% increase in cortisol over 2 weeks, that's going to start having effects on the brain and the body. So, what we did is we went back to Addenbrookes Hospital and we replicated that hormone profile in a group of volunteers. Gave them a risk taking task and what we found is that the chronic stress caused their risk preferences to more or less collapse.

Chris - What was the hormone that you were manipulating?

John - It was cortisol which is the main stress hormone produced by the adrenal glands which sit on top of your kidneys.

Chris - So, you elevate the cortisol levels in this group of volunteers who are not traders in this instance. They're just normal volunteers and you're saying that their choice of whether they want to take a risk or not changes in response to that elevated cortisol.

John - Correct.

Chris - In what way does it change?

John - They become much more risk averse. When given the opportunity to choose between gambles, in other words, if you had a choice between flipping a coin which will give you 100 pounds if head came up zero if zero came up, your expected return from that gamble is 50 pounds. If people would prefer to take 25 pounds for certain rather than play that game, then they're very risk averse. And so, you can measure people's risk preferences by the amount of money they would take for certain rather than take chances on making a lot more money. We found that under placebo conditions, people would say on one bet would prefer 40 pounds for certain and then when they were chronically stressed, that might drop down to 25 pounds. So, they're becoming very much more risk averse.

Chris - So, this suggests that these people at Addenbrookes Hospital, if their performance were extrapolated to what's going on in the stock market, then traders may be becoming a lot more risk averse under high volatility, high market uncertainty conditions. So, what would be the long term impact on the markets then?

John - Well, we think what happens is volatility and uncertainty in the markets spikes most dramatically during crisis. We think what happens is that this mechanism that we've uncovered, this effect of chronic stress - not acute, but chronic stress in promoting risk aversion, it may be a physiological mechanism that morphs a bare market into a crash or a crisis. So that for example during the credit crisis a few years ago when volatility spiked to astronomical levels and stayed there for a year and a half. We think the financial community, under the influence of stress hormones became pathologically risk averse. They just would not buy risk assets no matter how attractive they became. That meant that the financial community could no longer perform the task allotted to it which is to buy cheap assets and stabilise the markets. They couldn't do it. The central banks had to step in and do it for them with these quantitative easing programmes.

Chris - Does this mean then that before I make an investment on the stock market, I should be phoning up my broker and asking for a sample of testosterone and also for a sample of saliva to look for their cortisol, to see whether they're likely to make risky bets or not?

John - Well, there are probably other way to doing it, but I mean, it sounds farfetched, but to tell you the truth, this is what sports physiologists do all the time with their athletes.

06:22 - Brain-training boosts ball skills

Brain-training boosts ball skills

Brain-training exercises to boost visual awareness might be the way for baseball players to gain an edge over the opposition, new research has shown.

Previous research into visual ability has tended towards visual exercises that work out the  muscles of the eyes, rather than improving their ability to do real-world tasks.

muscles of the eyes, rather than improving their ability to do real-world tasks.

Now, Aaron Seitz and his team an the University of California, Riverside, writing in the journal Current Biology - took 27 of the Riverside baseball team's players before the start of the 2013 season, and made 19 of them do 30 lots of 25-minute visual training, using a special video game. As a control, 18 team-mates weren't made to play the game.

Impressively, the baseball players who did the video training saw an average 31 per cent improvement in the accuracy, or acuity, of their vision - being able to see more letters on an optician's chart - as well as greater sensitivity to contrasts in light.

The benefits translated out of the lab and onto the field, with the trained players reporting, "seeing the ball better, greater peripheral vision and an ability to distinguish lower-contrast objects."

Not only that, but they had 4.4 percent fewer strikeouts - an impressive drop compared to all the other teams in their league - as well as scoring 41 more runs than expected over the season, and showing greater improvement in other stats than other teams in the league.

Overall, the researchers think the benefits of the brain training for just half the players added up to an extra four or five wins over the season - although it's too early to know if changes in vision were solely responsible for the improved play or if brain-training combined with unmeasured factors bettered batting performance.

Baseball, like a lot of sports, is weighted towards visual accuracy - obviously, you need to see the ball coming if you're going to hit or catch it. What's special about the Riverside brain-training approach is that it focuses on training the brain to better respond to the input it receives from the eyes in real-life situations, rather than just making the eyesight better.

So, it might well benefit players of other, similar sports - for example, the researchers are starting a new study with the women's softball team. Also, the researchers think that this type of training might help non-sporty people too, improving tasks like reading or driving.

Finally, it's worth pointing out that the best visual training in the world isn't always enough - the Riverside baseball team had to forfeit eight wins due to having an ineligible player on the team. Perhaps they should have read the rules a bit more closely...

09:24 - Winter Olympics

Winter Olympics

The Winter Olympics are finishing in Sochi, Russia this week. But it's not just the  athletes who've spent the last four years training for the event. Engineers and designers have also been working to reduce times and grab golds on the slopes. In fact, when asked about her gold medal in the Women's Snowboard Cross Eva Samkova from the Czech Republic said "It's just physics, that's all,". To find out more, here's your Quick Fire Science with Kate Lamble and Harriet Johnson.

athletes who've spent the last four years training for the event. Engineers and designers have also been working to reduce times and grab golds on the slopes. In fact, when asked about her gold medal in the Women's Snowboard Cross Eva Samkova from the Czech Republic said "It's just physics, that's all,". To find out more, here's your Quick Fire Science with Kate Lamble and Harriet Johnson.

· - Friction, air resistance, and gravity are the main forces that track and equipment designers working on the Winter Olympics need to consider when they are trying to make times as quick as possible.

· - In order to reduce friction, skis and snowboards are waxed before use. A professional wax technician has around 500 different products to choose from and selects the right wax for the snow conditions.

· - When the snow is wet, a water repellent additive called fluoro, is increased in the wax, but this can create more friction if too much is added. Antistatic waxes can also be used to reduce electrostatic charges which can build up over long races.

· - Snow type has been a problem for some races in Sochi with snowboarders complaining of soft snow in the halfpipe. By spraying water and salt onto tracks organisers hoped to melt this soft top layer before allowing it to freeze again into harder ice.

· - Rather than snow, ski jumping tracks are actually made from ceramic. When moistened with water, these have the same friction characteristics as snow but allow the sport to be conducted all year round in almost identical conditions.

· - To combat air resistance special skin tight suits are worn in a number of sports. However Team USA have just dropped their newly designed speed skating outfits following poor performances.

· - There have been some suggestions that vents on the backs of the suits, designed to dump excess air might instead be causing a slight drag effect. While this hasn't been proven the team chose to swap the suits as athletes were concerned about the possibility of their performance being affected.

· - In other sports, equipment is also important to help athletes perform at their best. In luge, weight vests can be worn by lighter competitors to minimise the advantage carried by their heavier peers.

· - In curling, players wear one rubber soled shoe to allow them to push off from the ice and one teflon soled shoe. The teflon has a reduced friction coefficient and so allows them to glide across the ice.

· - Commercial companies also help in designing equipment. Great Britain's gold medallist in the women's skeleton had her sled designed by motorsport company McLaren. The designers used computer simulation to make sure it could be adapted to suit a range of different tracks.

12:18 - Biomarker for depression?

Biomarker for depression?

with Professor Ian Goodyer, Cambridge University

This week Cambridge researchers identified the first biomarker for major, or clinical,  depression. This 'biological signpost' could mean boys at greatest risk of depression are diagnosed earlier.

depression. This 'biological signpost' could mean boys at greatest risk of depression are diagnosed earlier.

Chris Smith spoke to Professor Ian Goodyer who led the study...

Ian - Clinical depressions are a whole group of as yet, poorly understood conditions, they emerge in the teenage years in the main. Between 13 and 17 years of age, about 1 in 6 to 1 in 10 of young people are going to experience depressions and about 30% of those are going to be quite severe, taking you to hospitals, GPs and in some cases, to psychiatrists and mental health specialists.

Chris - It's a very large number.

Ian - It is a large number. But there are many different kinds of illnesses in there. Some of them will only last for a few days or weeks. Unfortunately, some of them will last for many years and very occasionally, for the rest of your life. What we don't know is how to spot individuals in the community at large who would be at different types of risks for different kinds of depressions. People have been trying for some time - perhaps up to 30 years - to find markers in individuals that put them at risk for one or more of these kinds of depressions.

Chris - I presume, if you have some kind of marker then you can put people into a different category and different categories are going to require different treatments or interventions, and have different prognoses attached to them.

Ian - It would be the aim and objective to get to the kind of paragraph you just summarised. If we can find markers, does that allow us to identify groups at differential risks? Does that mean we can plan different kinds of interventions at the public mental health level? Or indeed, as you implied, at the clinical intervention level? Long way to go, but it's about time we started going down this path.

Chris - So, have you done this?

Ian - Well, for many years, we've known that the HPA axis - that's shorthand for the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis - releases a hormone called cortisol which moves up and down at different times of demand on the individual. It's a very important hormone. It's got nothing to do with disease. We need it to stay alive and it gets into all of our cells all over the place including the brain. About 40 years ago or so, some scientists in the states and in Europe showed that some individuals who were depressed had very high cortisols. At first, it was thought, well, this is just a consequence of being ill like having a high temperature. I think the initial excitement died off. But in the last 20 years, people have noticed that morning cortisol levels can be high in some individuals in the population at large who are not ill. That's intriguing. So, we started off over 2 decades ago in trying to figure out if high morning levels on their own were associated with the subsequent increase in onset of any kind of depression. The answer was yes.

Chris - Were you looking at blood or urine levels for that?

Ian - Well, we had to do the usual technical work. First, we had to develop an assay that was sensitive and specific enough in the lab. We then had to show that levels in different bodily compartments were correlated with each other. So, we did a study comparing CSF blood and saliva levels in different populations and showed that the levels in saliva were estimable with respect to blood which was estimable with respect to the CSF levels.

Chris - CSF is cerebrospinal fluid around the brain.

Ian - Yeah, the fluid around the brain. What that meant was that we could take saliva levels in the population at large and make some degree of interpretation about its implications for the brain. Now, that took 2 decades and then the study that we just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and funded by the Wellcome Trust, that took a decade. So, we needed approximately 1850 teenagers in two slightly different studies. The second thing we needed which has not been done before was, we needed to do this longitudinally.

Chris - So, you need to know, does one beget the other subsequently. If we have one at one point in time, do you then get the depression or the other illness later?

Ian - That's right. There's a bit of important mathematics because you have to try and establish longitudinally over 12 to 36 months, the relationships between depressive symptoms themselves and the relationships between different cortisol levels themselves. Then you have to put the two together. And that's how you create different classes in the population at large.

Chris - What have you found?

Ian - So, about 17% of the teenage population had both high long term depressive symptoms. Not clinical, just the kinds of things you and I were talking about and high long term morning cortisol levels. So, when you were in the group with the high depression, high cortisol level bit and you were a boy, not a girl - that's an interesting and slightly surprising finding. Then your chances of being depressed over the coming months, were about 14 times higher than either boys or girls in the rest of the population.

Chris - Which I presume means that we now have an opportunity to use this as some sort of screening test in order to identify people who might be at major risk.

Ian - Absolutely. It's ironic that about 25 years ago, GPs asked me if there'd ever be a screening test using cortisol. I said I wasn't sure. Well, here's our chance.

18:01 - Making platelets

Making platelets

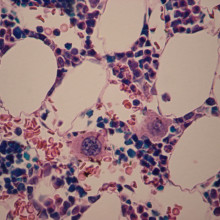

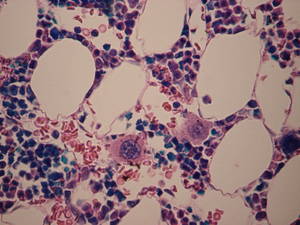

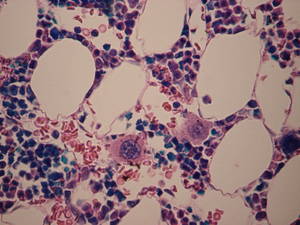

A way to grow blood platelets, a critical ingredient in the cogulation system, has been announced by scientists in Japan.

When you cut yourself, tiny little blood cell fragments called platelets  rush to the rescue, helping the blood to clot and the wound to heal. They're a vital treatment for people hurt in accidents, or those with certain blood diseases, but they can only be gathered from blood donations. And, as any doctor will tell you, there are never enough donations, especially because platelets have to be kept at room temperature and have a very short shelf-life.

rush to the rescue, helping the blood to clot and the wound to heal. They're a vital treatment for people hurt in accidents, or those with certain blood diseases, but they can only be gathered from blood donations. And, as any doctor will tell you, there are never enough donations, especially because platelets have to be kept at room temperature and have a very short shelf-life.

But this could be about to change, thanks to an important new paper from Dr Koji Eto and his team in Japan, published in the journal Cell Stem Cell. In it, the researchers describe a new way to create platelets from stem cells grown in the lab, potentially reducing the need for donated platelets in the future.

The researchers used a recently developed technique that we've heard a lot about lately - so-called induced pluripotent stem cells, or IPS cells. This is a way of turning adult cells into stem cells by adding a handful of protein factors - a discovery that won Japanese scientist Shinya Yamanaka a Nobel Prize in 2012.

Eto's team treated IPS cells with a cocktail of genes that converted them into a type of cell called a megakaryocyte - a large precursor cell that produces platelets. And the platelets the converted cells made had similar clotting capabilities to platelets from donated blood.

Scientists have previously tried to create platelets from reprogrammed stem cells but the yield has been very low, whereas this new technique produces large quantities. Furthermore, the megakaryocyte precursors can be safely frozen, and could potentially be grown on a large scale, which might mean platelets on tap on the future.

20:06 - Powering-up growth factors

Powering-up growth factors

Growth factors with powerful wound-healing effects have been developed by Swiss researchers.

Tissues respond to injury by making cells grow and divide to knit wounds together.  Usually this occurs in response to the release of growth-stimulating signals called growth factors.

Usually this occurs in response to the release of growth-stimulating signals called growth factors.

Previously, scientists have shown that supplementing an injury with these factors can speed up healing, but side effects, including making blood vessels become leaky, mean that only small doses can be used, limiting the therapeutic potential of the agents.

Now, Ecole Polytechnique Federale, Lausanne, scientist Jeffrey Hubbell and his colleagues, writing in Science, have found a way to boost the power of the growth-promoting effect by confining the agents just to the site of administration.

Applied to diabetic mice with skin wounds, the new agents produced up to four-fold greater wound closure compared with control animals. There were also significantly more cells capable of forming new blood vessels in mice receiving the new agents, and rates of blood vessel leakage were only a ninth as high as animals given conventional growth factor treatments.

The key to the breakthrough was the identification of a sticky component that behaves like molecular velcro and is capable of gluing growth factor molecules onto the connective tissue at the site of a wound.

Taken from the placenta, where it is normally active, this sticky component was instead coupled by the Swiss team to growth factor molecules called PDGF (platelet derived growth factor), which attracts stem cells to injury sites, and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), which triggers new blood vessel formation.

Dripped onto the wounds, the modified forms of these factors tethered themselves onto the injured tissue so that they remained actively locally but not elsewhere in the body.

Since the same factors are active in the human body, as is the placental component that was used as the "velcro", the same approach could be used clinically to stimulate localised healing in injured or diseased organs, including the heart, skin and even the eye...

22:16 - The Winter Vomiting Virus

The Winter Vomiting Virus

with Professor Ian Goodfellow, Cambridge University

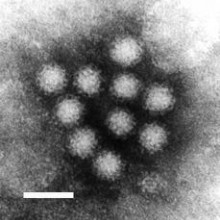

Norovirus, or the winter vomiting bug as most people call it is the most common  stomach bug in the UK, affecting up to 1 million people a year and it's particularly prevalent at the moment.

stomach bug in the UK, affecting up to 1 million people a year and it's particularly prevalent at the moment.

Chris Smith caught up with Ian Goodfellow, from the Department of Pathology at the University of Cambridge, to find out more about what we know about the virus.

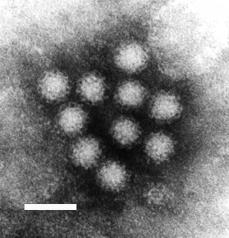

Ian - Noroviruses are small highly infectious viruses that cause gastroenteritis. They're typically referred to in the public press as the causative agent of a winter vomiting disease. But outbreaks occur all year round. The reason they're referred to as winter vomiting disease is simply because of the peak incidence appears to occur in and around the winter months.

Chris - Why is that?

Ian - It's probable that they tend to survive longer in the environment in the cold and wet. But also, people tend to spend a bit more time together during the winter. The reality is, we still don't know. It's one of the important questions that need to be addressed for noroviruses.

Chris - When you say the agent lurks in the environment, give us a sort of a snapshot view. What do these viruses look like and how do they get into the environment?

Ian - So, these are tiny, tiny little viruses, one of the smallest viruses around. The virus culture, the shell is made up entirely of protein. So, this makes them particularly resistant to inactivation by detergents and things like that. They get into the environment primarily through the vomiting or the diarrhoea episodes. People would have to get into the sewer systems and they contaminate the water courses. They often will also contaminate shell fish and people will get norovirus infection from eating contaminated uncooked shell fish.

Chris - When you say that it can stay in the environment, if a person is symptomatic in an area, how long will that area retain virus that's capable of infecting someone?

Ian - Probably in the region between 7 to 10 days. If not, longer. If it's untreated, it is probably going to remain enough infectious material that infects somebody for at least a week. This is partly because you need to be exposed. Very few particles are required to become infected so less than 20 particles are thought to be enough to cause an infection.

Chris - When a person is symptomatic, to put that into perspective, how much virus are they shedding?

Ian - An individual would normally shed somewhere in the region of a million or more virus particles per millilitre of faeces or vomit, and you need only 20 to infect an individual. So, each infected individual can infect many million others.

Chris - Wow! It's amazing to think there's millions of infectious doses in every single person, isn't it?

Ian - Absolutely.

Chris - So, when I ingest norovirus, I've got to pick it up from the environment. It presumably gets either onto the food I'm eating onto my fingers and gets into my mouth and I then swallow the particles. What happens next?

Ian; - That's a very good question. In fact, we don't really know much about the life cycle of noroviruses particularly in the gut. So for example, we know it grows in the intestine, but the reality is, we don't know precisely what cells in the intestine it infects. What we do know is it basically mimics the body's response to eating something that's poisonous. It stimulates this response known as the emetic response where effectively, your body will eject all the contents of the stomach and this is the vomiting episodes that you get. And then you will flood the intestine with fluid to try and wash out any poison. We think what the viruses do in stimulating this process either directly or indirectly by interacting with certain cells of your nervous system.

Chris - What about other animals because people often ask me, "Can my dog give me diarrhoea?"? Do we exchange these infections with animals or is this purely a human infection?

Ian - This is a very good question. Norovirus has been identified in a whole range of animals and there appears to be very specific noroviruses for cats, for dogs, for cows, for pigs for example. But there is limited evidence now that human norovirus can be found in the pig population. Whether or not there's this [genetic] transfer from pigs to humans is not entirely known. And in fact, there's limited data as well to say that in some cases, human noroviruses can be found in dogs and this is something that we're working on my lab to try and see if this is a common occurrence. At present, we think that human noroviruses are not a [genetic] disease so they primarily infect humans.

Chris - When I catch it, am I immune to it almost immediately that I've caught it. Is that why the symptoms go away because the symptoms do go away pretty quickly? Within 48 hours, you're feeling all right again usually, aren't you?

Ian - That's right, but it's likely you don't generate a very good immune response and we think one of the reasons these are such effective pathogens is simply because you don't generate long lasting antibody responses to this virus. It's more a process known as you're innate in your response. It clears the virus so the virus is not there for very long. Therefore, we don't generate very good antibodies. So, we can be re-infected probably once every year by the same virus.

Chris - Got you. Are there also lots of other strains circulating? So, although I've had one type previously, I may in fact pickup another next week to which I have no immunity and I can go down with this again?

Ian - Yes, again so one of the features of these viruses is that every time they multiply or copy the genetic material, they make mistakes. This means the virus can evolve very rapidly. Typically, in any one year, you'll find that there are at least one dominant strain or isolate of norovirus, but that will evolve. There'll always be minor species within that. In fact, within any individual who's infected, whilst maybe one strain of virus, each individual virus particle will contain a slightly different sequence. This gives the virus the ability to evolve away from any immune response.

Chris - Does that frustrate efforts to make a vaccine then?

Ian - This causes a lot of problems to the vaccine production. However, there's very encouraging data coming from a company known as Takeda. Their data suggests that you can protect from infection if you immunise individuals with the same type of norovirus strain and that will protect primarily from symptoms. So, less than 50% of individuals who develop symptoms and this can prevent spread. It's likely though if norovirus vaccine becomes viable. It's likely it would need to be changed every year, very similar to the influenza virus vaccine. However, us and a number of labs around the world are trying to develop new vaccines that give cross protective immunity. Probably in the next 5 to 10 years, they'd be looking at larger scale trials of human norovirus vaccines.

Chris - Thank you very much to Ian Goodfellow, from the Department of Pathology at the University of Cambridge.

30:00 - How does Norovirus Spread?

How does Norovirus Spread?

with Lydia Drumright, Imperial College London

Lydia Drumright from Imperial College London is undertaking a new study to find out  how the virus infects people and how long they remain infectious for. Kat Arney spoke to her.....

how the virus infects people and how long they remain infectious for. Kat Arney spoke to her.....

Lydia - Hi, Kat.

Kat - So, tell us a little bit about what do we know so far about kind of the life history of norovirus. How it infects us and where it goes in populations?

Lydia - We actually don't know a lot about that. There's a number of studies that have been conducted, looking primarily at the strains that Ian talked about, the predominant strains in Sydney that people may have heard of recently which was last year's strain was reported on quite widely. But one of the important factors is that we only look where people are symptomatic. So, where people are part of an outbreak, those are who are collected into studies. What our study will look at is not only those people, but all the people around them because we're concerned that people are becoming infected and shedding without actually being symptomatic.

Kat - So, the main way that you get rid of virus from your system is by vomiting and diarrhoea. How could people just shed the virus when they're not having severe symptoms?

Lydia - So, the thing about infectious diseases that we're learning is that actually, we have what we call carriage and we have what we call infection or symptoms. And so, you don't actually get rid of the virus by vomiting or having the diarrhoea as Ian had mentioned. You get rid of it by an immune response. And so, the process of shedding the virus happens whilst it's in your body and different people have different immune responses.

Kat - So effectively, you can be not vomiting, not having diarrhoea everywhere, but you can still be dispensing virus to your family, your friends, your colleagues?

Lydia - Exactly, secretly dispensing virus if you will.

Kat - So, what are you trying to do with this study? As you're studying it in people in populations, you're also trying to find out where does it hang out? As Ian said, it can hang around in the environment for up to 10 days.

Lydia - Exactly. So, we're using hospitals as sort of our microcosmic environment if you will and we are swabbing the ward areas. So, people have done this after there's an outbreak and they see lots and lots of norovirus. We want to swab all year round, so we're doing weekly swabbing to see when it's there, if it's there, where it's hiding out, and also, looking at the symptomatic and asymptomatic people.

Kat - And do you have any idea of the kind of patterns that you're looking for?

Lydia - So, what we're looking for and we might be hoping to see is that actually, environmental swabbing will tell us when we should be expecting outbreaks in the hospital. So in other words, we might not see any norovirus, or we might see it at a very low level, and then as that level increases, we wonder if that will lead to outbreaks or not.

Kat - The results from that could be really powerful for hospitals trying to cut down on infections. It surprises me that this kind of thing isn't done already?

Lydia - I would agree with that. I think that there's been a lot of challenges to funding environmental studies and this was the one question I think reviewers had on our study as well. They said, "Well, I'm not sure how strong of a component the environment is, but we like the rest of the study, so go ahead and fund it." But actually, I think the environment is very important. We talk about it a lot for MRSA and other infections that we know about and we just don't know how it's playing a role.

Kat - And it seems quite sobering as well that as Chris said, the advice is, once you've had norovirus, after about 48 hours, you're feeling okay again. It's quite sobering to think that people could be infectious for much longer than that. Do you think that that should change advice on what people should do?

Lydia - At the moment, I would say no. So, we do know from previous studies where they infect people, deliberately, healthy volunteers, with norovirus that the average healthy individual sheds for up to 3 weeks. What we don't know is, how infectious that shedding is and how that contributes to the environment or further outbreaks. So, at the moment, we should probably stick to the guidelines because we don't want healthcare workers certainly off for 3 weeks. That would cause a huge problem for the NHS.

Kat - Well, especially if people are feeling fine again after 2 days, I guess. But thanks very much. That's Lydia Drumwright from Imperial College London.

34:55 - Washing your Hands!

Washing your Hands!

with Rachel Thaxter, Addenbrooke's Hospital

If someone you know has norovirus how can you protect yourself? Infection control  nurse Rachel Thaxter joins Chris Smith in the studio to show us how to wash our hands properly..

nurse Rachel Thaxter joins Chris Smith in the studio to show us how to wash our hands properly..

Rachel - This is a gadget we use in hospitals to teach student nurses and medical students how to wash their hands. We use a cream that's got a UV impregnated particle in it and we asked the staff to put this cream onto their hands and rub it in like hand cream all over the surface of their hands and their nails. We then asked them to go and wash their hands and see how successful they are at actually washing this cream off.

Chris - Because if they were potentially infectious for norovirus or had contacted a surface with norovirus, hands are presumably the main route via which infections spread.

Rachel - Yes, hands are key in all infections really. So, good hand washing, good hand hygiene at all times is what we recommend.

Chris - Well, I found you a victim. Harriet Johnson who's here with us from the Genetic Society. How's your hand washing, up to spec?

Harriet - They look pretty clean. They look alright.

Chris - What do you want her to do, Rachel?

Rachel - I'm just going to put some cream onto Harriet's hands. So, just a nice splodge of that. all of your hands like a hand cream, your nails, your wrists, your thumbs.

Chris - So, this is called glow and tell. So, this is just a dye which will glow under UV. The idea being that you're going to send her off to wash her hands.

Rachel - That's correct, yeah.

Chris - And if she misses bits, we'll know.

Rachel - We will, yeah. It's not actually highlighting the bugs on the skin. It's just like a cream which will then dry and wash off to mimic the possibility we have all these bugs on our hand and Ian said there's thousands of them. So, off you go and wash your hands.

Chris - Okay, Harriet so, off you go and wash your hands now as you would do normally. So, just how you would judge your hands to be clean after washing say, you've been to the loo or something. I presume you wash your hands after.

Harriet - Yep, always, never a walker.

Chris - We'll see you in a minute. So Rachel, what some practical tips can you give people if someone goes down with D&V in their house? What's the best way of someone not spreading it around the family?

Rachel - Isolate yourself. So, stay in your room. If you've got the luxury having many toilets in your house then try and allocate a toilet to the sick individual with their own hand washing basin. If you haven't got that luxury, then making sure that the affected person has their own towels and flannels. There's no sharing of those kind of items. Keep yourself hydrated. We don't really want the sick person preparing meals for the family. Obviously, if that's vital then scrupulous hand hygiene will be needed. Keep yourself segregated until your well. As we said, that normally is within 1 to 2 days and then you can start getting things back to normal within your lifestyle. And that's why when you come into the hospital, we ask you not to come if you've been unwell and not to come if you've been unwell in the last 2 days. We don't want the community bringing bugs into the hospital and then giving it to our vulnerable patients. At the moment, we've only got I think 2 or 3 cases in the hospital Chris. So, we know it's out in the community. I mean, we want to keep it that way.

Chris - What about the cleanup measure because we hear a lot about people saying, "I use alcohol hand rubs and I wipe the taps" and that kind of thing? What practical advice can you give people for a.) their own hand hygiene to make sure that they don't either transmit it or pick it up and b.) cleaning surfaces where someone has been unwell?

Rachel - Alcohol gels are really good in hospital when we've had social contact with patients and we're not dealing with patients who are unwell or dealing with their body fluids. Really, in the home, I only use hand gels if I'm out on a picnic or somewhere where I can't actually wash my hands properly. I don't use it as a substitute to washing my hands. So in the household, good old fashioned soap and water is the best thing.

Chris - Because I did read that those alcohol gels are actually no use against norovirus because like Ian was saying at the beginning, it's a particle that doesn't get broken down by alcohol.

Rachel - That's correct. So again, we're ask you not to use it in hospitals when we have problems and say, not use them at home as a hand hygiene product.

Chris - Mark has got in touch and says, "How long does it take for symptoms of this to come on? I'm surprised I've not caught it from spending time on underground trains that are packed with people from around the world."

Rachel - It's pretty rapid I think as we all know if we've looked at people with it. People can feel fine at 10:00 o'clock in the morning and then half past 11:00, actually vomiting and feeling really unwell. They tend to look a bit grey and ashen. So, it's a bit of a giveaway then. But as I say, normally, the patient can be quite well and then suddenly, they'll just be unwell. So, you may well have to clean up at home. And again, good cleaning, you can use sort of bleach based products. They're good for cleaning body fluids. If your clothing become soiled or bed sheets then wash them on a hot wash and again, do them separate to the rest of the family.

Chris - Our hand washing victim Harriet is back. Did you do a good job?

Harriet - Yeah, I did what I regularly do.

Chris - You would judge your hands to be clean. Rachel, what's the verdict?

Rachel - Let's pop your hands into my UV box, Harriet. Okay, so we can see actually the areas that Harriet hasn't washed quite as well as she thought she had, are glowing nice and bluey white under my UV box.

Chris - All the backs of her hands.

Rachel - The backs of her hands.

Chris - Where her watch is...

Rachel - Yeah, you can see where her watch is. Which is why we don't wear watches in the hospital or bracelets because we need people to be bare below the elbows, so they can wash their hands properly.

Chris - Too much bling, Harriet.

Rachel - There's quite a lot as well around your finger nails there. So again, these areas, you'll find it difficult to wash and also, Harriet is showing quite nicely that her thumb on her less dominant hand is pretty well covered whereas her other hand is quite good. So, if your right handed, you washed your left hand really well, but if your - obviously, your dominant hand is the one you're going to be doing all the things with and that's the area unfortunately we don't wash as well. So, it's quite a big difference between Harriet's right and left thumb and as Chris said, that she got loads in the back of your hands, Harriet there. You've done quite well in the front of your hands. It's really just showing up all the nooks and crannies where bugs can be hiding. And also, if your skin is quite dry like it is in the winter then again, these areas where bugs can hide quite happily.

Chris - I suppose it's worth emphasising as Ian Goodfellow pointed out the infectious dose for norovirus is 20 particles and each person is shedding millions and millions. Enough in fact to infect the entire world from one infectious person. And any patch of Harriet's skin could have easily an infectious dose of noro.

Rachel - It could, yeah. What do you think, Harriet?

Chris - What do you think about it? Are you shocked?

Harriet - Yeah, yeah I'm filthy.

Chris - We know that, but I mean, were you quiet surprised at the finding?

Harriet - Yeah, I mean, there were ones that I was expecting like the back of the hands. I always think people don't pay attention to that, but I did find the difference between the two hands themselves interesting, as one of my hands is dirtier than the other one. So, I'll change the way I shake hands next time.

Chris - Rachel, one quick question from Jonathan Bowman who got in touch and has said on Facebook that, is it true that it's virtually impossible to eradicate norovirus from surfaces without resorting to industrial strength bleaches, presumably and hopefully not?

Rachel - I mean again, good soap and water, so good basic cleaning you have in your house. I'm not sure whether Lydia knows any more than that, but generally, infection control is all about good hygiene and common sense. So, what do you think Lydia? Can you help me out there?

Lydia - Yeah, actually, in studies where they were cleaning wards and then swabbing afterwards to identify whether or not they cleaned well, they actually did show that a bleach, type of 10% bleach solution plus additional soap and water washing was what was required. So, my guess is it's repeated washing if you can't use a 10% bleach solution.

Chris - Thank you to both of you. Kat...

41:53 - The healthcare cost of norovirus

The healthcare cost of norovirus

with Keith McNeil, Addenbrooke's Hospital

How do hospitals protect their patients against norovirus, and how much does this bug cost them every year? Kat  Arney speaks wiith Keith McNeil, the chief executive of Addenbrooke's hospital...

Arney speaks wiith Keith McNeil, the chief executive of Addenbrooke's hospital...

Kat - So tell me for you, running a big major hospital like Addies, what are the costs of norovirus?

Keith - Well, that's a very complicated question and it's multifactorial. So, in principle, any illness that adds to the complication of an admission of a patient to hospital adds additional cost. If it's a young healthy adult and you get norovirus, and they lengthen their stay by a day or so. Or they may be ought to be discharged appropriately. But if you're frail and elderly or you have an immune disease or complicated surgery, your stay in a hospital can be lengthened quite significantly. If you are on the intensive care unit, it can be devastating. So, it's difficult to quantify in absolute terms. The other thing is, of course, once we get norovirus in the hospital in significant numbers, we have to escalate to stop it from spreading and that can mean isolation of patients or even closure of entire wards or bed bays to stop that virus from spreading. That then has flow on effects in terms of our ability to do the work that we're setup to do - to do elective surgery to service the emergency room and flow patients through. And we have a problem then in generating the income that we need through that activity. So, a big outbreak is costing us hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Kat - I guess also there's a risk that your staff would get it too and suddenly, you'll find yourself with no doctors and nurses.

Keith - That is a big risk. I think that's been pointed out by the two ladies on the panel that infecting the staff and knowing how long they're going to be shedding for and potentially spreading it further is very important to us.

Kat - Addenbrookes is doing quite well I understand in terms of keeping norovirus out. What's the worst you've ever seen it there and what do you think is the secret to your success at the moment?

Keith - Well, I've only been in Addenbrookes for 12 months now, but I do understand that a couple of years ago, I think there were 5 or 6 wards closed which is a tremendous burden on the hospital and on the whole community. So, whenever that sort of thing happens, we've got escalation protocols to try and lock it down as quickly as we can and prevent it spreading further - deep clean the wards, we highlight the need for people not to turn up if they don't have to, restrict visitors, etc.

Kat - What do you think if you could tell people listening to this, what are the key things that the public can do to help you keep noro out of the hospitals?

Keith - Whenever they come in to the hospital, make sure they wash their hands when they come in when they go on to the wards, and when they leave the wards. So, hand washing has been highlighted as being very important in controlling this infection.

Kat - I guess the irony is, if you actually have noro, the last place you should go is a healthcare facility like your GP or a hospital. If people have it, they should just stay in I guess.

Keith - Well, if they're otherwise well, yes, they should. It's usually self-limiting in healthy people. If you're otherwise unwell, of course sometimes, you just have to turn up and receive care. But certainly, if you've got these self-limiting illnesses you should try and stay away from other people and particularly from health facilities whenever you can.

Are there any hand gels that kill viruses?

Rachael - Well, you can't hydrogen peroxide onto your skin of course, but we do use that in a vapour form we're cleaning our wards. We do deep clean areas that have norovirus outbreaks or side rooms that have had patients who've been infected in them. So, we do quite robust cleaning at Addenbrookes using the HPV process. So, you can't get a spot into your skin. They're highly toxic in higher concentrations that the vapour forms are very small amount of agent that's there. It is very effective at cleaning our environment. Some of the gels do claim to be effective against flu virus and things like that, but as we've said really, although they say they are, it is always the best gold standard to wash your hands, if you've got that facility, so gels are so useful in a hospital for social interaction with patients and really useful if you're in a situation where there isn't hand washing facilities such as on a picnic or family holidays and things like that. But we generally say, although they say on a label, "We will kill flu", "We will kill viruses", we generally say, we shouldn't rely on that.

Are there different norovirus strains?

Lydia - Yes. So, one of the things that we've noticed with norovirus in all the sampling that there is, is there are a number of different strains. We call these genotypes of norovirus and there are also geno groups. So, there's kind of a wide variety. And as you mentioned Chris, you could be presumably infected twice in a year or even in a short period of time by two different strains. Although as was mentioned, there are predominant strains that circulate. Now, these move around the world quite rapidly. We've seen looking at all the data that those in GenBank, so that's everybody's analysis of the virus from the genetic material in the virus. We can see the same virus moving for 10 to 20 years and spreading within the same year from the US to China, from the UK to Southeast Asia. So, really quite rapid spread.

Chris - Okay, so Keith, if Lydia's result show that people are infectious for 3 weeks, what's that going to do to your budget if you have to put the staff off work for 3 weeks?

Keith - I think it will come back to evidence as to what that actually means because we control outbreaks now without having staff off. So, the question I think is, how does that shedding actually translate into the spread of disease? We don't know that at the moment, but we'd be guided by the evidence. If it has implications, it has implications and we have to plan for that.

For how long is norovirus infectious in a house?

Infection-control nurse Rachel Thaxter answered this question...

Rachel - Well, at least for 48 hours.

Chris - I don't think he's implying he's going to cook dinner while he's having vomiting.

Rachel - Obviously not.

Chris - How long should people not come around your house for?

Rachel - If you're really good at cleaning, perhaps a week, clean your house a couple of times, your bathroom is the key area, the kitchen, a week.

Chris - So, defer that dinner party for a week Mark and you'll probably be alright!

49:12 - Why are MRI scans such low resolution?

Why are MRI scans such low resolution?

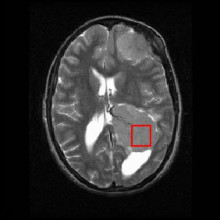

Hannah - So, whilst it might appear that MRI or magnetic resonance imaging pictures are blurry, in fact, they are not. As Paul Thompson, professor of neurology at University of Southern California explains...

Paul - Right now, the scans we use in the hospital can see small strokes and blood vessels as small as 1mm in diameter. The detail is terrific and brain scans can help diagnose cancer and Alzheimer's disease. The detail you can see depends on how long the patient can sit still in the scanner. It can take 5 to 10 minutes to get a brain scan and we can check parts of the brain involved in memory, language, and emotions. With a method called functional MRI, we can also see which parts of the brain are active while you're looking at a picture or speaking. Normally, it's hard to sit still for more than about 10 minutes. So, scientists are working on faster methods to speed up brains scans and get more detail.

Hannah - So, even though we can use MRI to take detailed pictures of brain structures, functional or fMRI looks at the activity of different brain areas by measuring how much oxygen they are using. But because the brain is moving and many measurements are taken over a period of time, the activity maps that fMRI produces tends to be of lower resolution which might explain why John refers to the images as being blurry. So, what about imaging to diagnose brain disorders?

Paul - Brain scans are often used in a hospital to see if a person's brain is damaged, if they've been in an accident or if they have memory loss, that could be a sign of Alzheimer's disease. Also, if a person has a stroke or a brain tumour, we can see clearly what parts of the brain are affected and we can see if the treatment is helping. Brain scans can also be used to plan a surgery that takes out of brain tumour while protecting the rest of the brain.

Hannah - And Paul is also part of one of the largest brain studies in the world called the Enigma Project. 307 scientists have scanned 27,000 people's brains including individuals with psychiatric conditions and results suggest that brain scans like MRI could be useful for distinguishing between Schizophrenia, bipolar and depression in the future. These disorders can sometimes be hard to tell apart clinically, so, this finding may help to diagnose people sooner so that they can receive the correct treatments early on.

- Previous Hirudin: Chemistry in its element

- Next Brainy Babies!

Comments

Add a comment