Q&A: Planets, Procrastination & Plastic Squid

This week, it is time to put your questions to a panel of excellent experts in one of our Q&A shows! We are going to be investigating what supermassive black holes do, strategies for coping with anxiousness and just how dog became man's best friend. Plus, we have a science quiz based on new beginnings and another mystery sound up our sleeve - see if you can guess what it is...

In this episode

01:15 - Meet our panel of experts!

Meet our panel of experts!

Olivia Remes, University of Cambridge & Greger Larson, University of Oxford & Becky Smethurst, University of Oxford & Thor Hanson, Science author

Julia - Let's meet this week's panel of experts. First off, we have a mental health and wellbeing researcher, Olivia Remes. Olivia is based at the University of Cambridge where she has studied anxiety and depression, as well as understanding the best coping strategies to help people thrive. These methods are documented in her book 'The Instant Mood Fix'. Olivia, as we are just coming out of January, what are some methods for lifting our mood during the winter months?

Olivia - One thing that I would say is turning to mindfulness meditation exercises. Something else that I would encourage people to do is to think of how you can incorporate a dose of positive emotion into your life. A dose of positive emotion can come from something that gives you pleasure that you enjoy, whether that's going outside for a walk in nature as being in nature is so good for our mental health and wellbeing. But also how can you get a dose of positive emotion in the home? A practical tip is to get into the kitchen. Cooking is great. Trying a new recipe changes how you feel about yourself. When you are successful with a dish, this can boost your self-esteem. These are all small steps that you can take to boost your wellbeing in these cold, dark winter months.

Julia - Yeah, I know. I definitely try to get myself outside when it's light and try to see the sun, but I love that about cooking a meal, especially a nice warm meal on a cold night. It sounds wonderful to me. Next up we have professor of paleogenomics at the University of Oxford, Greger Larson. Greger's research focuses on how we have evolved alongside other animals like chickens, pigs, and dogs. Greger, paleogenomics is a bit of a mouthful. What does that mean?

Greger - There's genomics, which is the sequencing of genomes, which every organism on earth has a genome. And paleogenomics is just trying to extract and amplify and sequence the genomes from things that have been dead for a while. As soon as you die, your DNA starts falling apart, just like the rest of you. What we are able to do is go and find some archaeological specimens, paleontological specimens, and many museum specimens. Then we're able to isolate the DNA usually from bone and teeth, but from just about any other substrate as well, including coprolites, which is like half-fossilized poo, but we can also use hair, plant remains, seeds, and all kinds of things. By extracting the DNA, we're able to then sequence and compare it against other living and dead populations to see what changes took place through time and space in order to try and piece that whole picture of evolution together over the last 50 to 100 thousand years.

Julia - I didn't think we'd be talking about fossilized poo, but here we are. Onto another evolution researcher now, but this time it's out of this world. Astrophysicist Becky Smethurst also based at the University of Oxford is with us. Becky studies the co-evolution of galaxies and the supermassive black holes and shares physics news on her YouTube channel, 'Dr Becky'. Becky, this may be a weird question, but what is your favourite black hole and why?

Becky - I think I'd have to say TON618, which is a very poetic name. TON618 is the biggest, supermassive black hole we've ever found. It is 68 billion times heavier than the sun and the really cool thing about it is we think it's reaching the biggest that supermassive black holes can ever grow to. Which is a really weird concept for people to wrap their heads around because people picture black holes like 'the endless Hoovers of the universe'. I like to say that black holes are less like hoovers are more like couch cushions. They're just very unassuming. You're not dragged towards them or pulled towards them, but if you lose anything down there, it's gone for good.

Julia - The couch is well and truly saturated. It's like that point where you're sitting on it, it's lumpy and you're like, 'Oh my goodness. There's so much stuff down here, but still I can't get anything out of it. I can't get anything out.' Finally on the show today from all the way across the Atlantic is conservation biologist and author, Thor Hanson. Thor shares incredible insights into all things wild and how our activities are influencing the creatures around us documented in his new book, 'Hurricane Lizards and Plastic Squids'. Thor, what is a plastic squid?

Thor - The plastic squid is a marvelous story that comes to us from the Gulf of California. There has been a traditional fishery targeting the humble squid, the jumbo squid which is a squid that can grow to 4-6 feet or almost 2 meters in size. But a few years ago, after a series of climate-driven marine heat waves swept through that area, people stopped catching these squid. They just disappeared. Everyone assumed that, like so many creatures on this planet, the squid had responded to climate change by moving elsewhere and looking for the conditions they're used to. It wasn't until some scientists went down to do some surveys that they realized that the squid were still there. Instead of responding to the increase in temperature by fleeing, they had responded with what biologists call plasticity. The squid were living half as long. They were eating different foods. They were reproducing in half the time. And under those constraints, their bodies were reaching only a fraction of their previous size. Too small to bite upon the hooks that fishers had previously been using to catch them.

Julia - Wow. So plastic in the sense of they've adapted to their environment, not in the sense of they look like a plastic bag.

Thor - Exactly. Plastic, meaning they are flexible.

08:17 - Ways to manage anxious feelings

Ways to manage anxious feelings

Olivia Remes, University of Cambridge

In the UK, it's estimated that around 8 million people live with some form of anxiety disorder. Julia Ravey interviews mental health and wellbeing researcher Olivia Remes about their scientific advice for dealing with anxiety.

Julia - What is your research found to be some of the biggest causes of anxiety?

Olivia - When it comes to what can increase someone's risk or the causes of anxiety, there are many different factors ranging from your environment. For example, your work environment - if you're dealing with stress at work this can increase anxiety, but also your relationships. Do you feel like you have fulfilling meaningful relationships, a support system, people that can support you when you're going through tough times. This is really helpful for mental health. If you feel isolated and lonely, this can also be linked to poor mental health. When we're looking at anxiety, another thing that is important is your early environment. The way that your parents raised you. Also there's a genetic component, so you can have a predisposition. The way that a mental health condition gets triggered in some cases is that you have this predisposition, and then along comes an activating life event. That could be maybe a stressful situation at work, or maybe a divorce or a relationship breakdown. When you add this to a predisposition, then this can be enough to create fertile ground for anxiety.

Julia - Your book, 'The Instant Mood Fix' gives some quick remedies for dealing with anxiety and stress. What are some of the strategies which could help people cope with these states?

Olivia - When we're thinking about anxiety, something that a lot of people with anxiety have in common is this tendency to focus on worst case scenarios. What I encourage people to do in my coaching practice or when people come to me for help, is I ask them to track their worries. Write down what is bothering you at the moment, and then write down your feared consequences. When we start logging them and coming back to them to see if they manifested or not, we see that most of the time they don't. It gives us a lot of hope, a lot of control over the situation. That's one thing that I would suggest for anxiety.

Julia - John asked 'What is one tip that can help someone and get over the hump of starting to exercise when they have anxiety?

Olivia - My one top tip would be, do it badly. This is for anyone struggling to get started on anything. Here's the context for that. Many times people aim for perfection. Perfectionism is getting in the way they can't get started until they've got all of the equipment they need to get started, or until they find the perfect gym to exercise at. All of this contributes to delays and procrastination. The antidote to that is to do it badly. Just jump right in without thinking about the outcome and without worrying about how it's gonna turn out. Just put your blinkers on and jump straight into it. I've had many, many people try this out and come back to me with positive feedback that it helped them to start taking risks. Things that used to be anxious became exciting. For example, getting started on a report for work, or getting started with exercising even. It got them to be unstuck. Do it badly and my question to people listening to this would be, if you were to start using this motto today, how would your life change?

Julia - I love that. I love that. Do it badly. That's what I'm gonna do going forward for sure.

13:46 - How long have dogs been man's best friend?

How long have dogs been man's best friend?

Greger Larson, University of Oxford

The top household pet in the UK is a dog. Known as man's best friend, fossil data has shown dogs have been our companions for a very long time. Julia Ravey asked Gregor Larson just how long have we had dogs as part of our pack...

Greger - That's a question that we're all trying to answer. We can give you bounds: we have an upper bound of 30,000-35,000 (years) and I think anything further than that is maybe a bit ridiculous and even I'm a little bit suspicious of that number. Then, a lower bound of maybe 14,000-15,000, something like that. So, somewhere in that period, there is a pack of wolves somewhere that goes from being very 'wolfy' to being very much associated with people. You get this emergent product of this changing relationship between people and wolves which results in what we would now recognise as dogs. That precedes any other animal with which we've made these amazing relationships by many, many thousands of years.

Julia - Did all the dogs we have today come from one pack millennia ago?

Greger - Another good question to which I will give you another ambiguous answer. We know it was grey wolves. We're not entirely sure which population of grey wolves or where they were at the time. We know that there were other populations of grey wolves that at some point contributed some of the DNA. Whether that was a completely independent process or not is an open question, but it was likely to be one primary source and then maybe a couple secondary and tertiary sources.

Julia - And what was it about these dog ancestors that made us join forces?

Greger - There are two schools of thought on this: there is the school of thought which theorises that it was very human led; very directed - we saw these wolves on the landscape and we thought either they looked cute or we can think of them as somehow being a really good partner in crime. So, let's steal a couple of puppies from a den, bring them over to the human camp (maybe even suckle them), take care of them, tame them and if they started to become a bit unruly, then we can knock them on the head or send them away. But for the ones that were quite nice, then we let them stick around, and then they started to produce more tame versions of themselves and, through that whole process, you get dogs. I am not a fan of that particular theory. I think that that's not how anything actually works within evolutionary biology or within the way in which we interact with the natural world and, instead, I think it was much more of an emergent process whereby you had a pack of wolves and a group of people and they started to form a kind of loose accidental alliance that then over a very long period of time started to result in both populations becoming more reliant upon one another. Now, as for the precise mechanisms that were driving this, there are a lot of different theories about that: there was one that was just published last year that suggests in the very Northern climes, where humans struggle to eat exclusively meat, wolves don't have a problem with this. So, if we were hunting a lot of mammoths, for example, in a very high step environment in Siberia or in the Arctic, there would be a whole lot of excess protein that we wouldn't necessarily be able to consume but those wolves would have, so they would've been attracted to us. We wouldn't have minded necessarily having them around because of a variety of other things that they could have offered us, including help with hunting or a number of other processes, but it's hard to recreate that. There's a lot more theories than there are answers at the moment, but I tend to think that the idea that it was much more of an emergent accidental process is the one that we should be asking the questions about rather than just insisting that we grabbed a couple of cute puppies and then we were done with it.

Julia - David asked if our pet dogs are more intelligent than other wild animals. Did we domesticate dogs to be good boys?

Greger - That question always bugs me because as soon as you use the word "domesticate" as a verb like that, it's conveying that we did something to something else and it implies this intentionality of the whole thing. And of course, as I'm sure the rest of the panel would agree, intelligence is such a plastic term. It's a super goofy amorphous thing and it's very context specific. So, there are the dogs within a human context who are very good at recognising our gestures, recognising us, recognising commands - they are going to be smart within that particular context - and there are wolves who are smart in their own context and their own environments where they don't do that, but it doesn't make them any more smart or more dumb. Any kind of very widely distributed species is very good at being distributed precisely because it's good at taking advantage of the local conditions in which it finds itself. So, the short answer to that question would be, yes, dogs are smart and are good boys precisely because they're here. It's a redundant question because we wouldn't have them otherwise.

18:55 - Could planet nine be a black hole?

Could planet nine be a black hole?

Becky Smethurst, University of Oxford

Becky Smethurst explains to Julia Ravey the possibility of a black hole affecting the Milkly Way as if it was a 9th planet...

Julia - So, the Hubble telescope recently detected a black hole which appeared to be giving birth to stars. Becky, is this what we expect black holes to do?

Becky - So, this is something we call "outflows" or "jets" from supermassive black holes. It really confuses people because the definition of a black hole is something so dense that not even light itself can escape, so when people hear about something coming off a black hole, it's very confusing. It's not actually coming from the black hole itself when we talk about outflows or jets. Essentially, as you chuck material towards the regions of a black hole, obviously everything is fighting to get into that black hole as that gravity is pulling it inwards. But, the material also heats up: it gets accelerated, it goes up to huge speeds and it actually starts to glow. Radiation like light starts to come off this material and you can get pressure from light. We talk about this radiation pressure like equipping spacecraft with solar sails - instead of wind particles hitting a sail, you've got light particles hitting a sail on a spacecraft in space and that can power it. It exerts a pressure that pushes outwards if you have this material around a black hole that can heat up, and it's actually how we spot the majority of black holes as well. They're some of the brightest objects in the universe which, again, is a bit of a weird one, but it pushes outwards against gravity pulling inwards. And so, if you actually chuck too much material in there, there's too much material that starts glowing that it actually starts to push back again, and you end up with this outflow from the black hole instead. I like to call it a black hole burp: it's like you fed it too much and it's just goes, "Eurgh! No", and that's what's happening. What I study is how those black hole burps can stop a galaxy from forming stars, but what the Hubble space telescope has found is that that burp is that actually causing stars to form.

Julia - James asked if two black holes can merge.

Becky - Yes. Two black holes can merge and we have actually detected signals from two black holes merging. These are not light signals - which is usually how we get anything from the universe, any information, whether it's visible light that we can see, or if it's radio waves or gamma rays or x-rays, they're all form of light - but for merging black holes, we get gravitational waves, which are essentially like ripples through space itself. Einstein said that gravity is like something massive which curves space, so you can picture this if you think of a trampoline or a stretched bedsheet, right, and you put a football in the middle of it and it will stretch your sheet out and it will curve the trampoline or the bedsheet. If you think about removing that, you'll get a shock wave that will go through the trampoline. So, if you have two black holes merging that are spiralling around each other with this huge effect because they're so dense, it does create these ripples that we then detect as the squishing and stretching of space.

Julia - And the last question we have here is, there's been some debate around if a ninth planet exists in our solar system. Do you think there is another planet or could it be something else?

Becky - This has been raging for year, even back to the 1800s when Neptune was first discovered and Neptune's orbit was a little bit weird and they thought, "maybe there's something beyond Neptune." And then of course they discovered Pluto and then they thought they'd solve that one and then it turned out Pluto was about the size of our moon and they realised it wouldn't be enough to shift up Neptunes orbit. Then, they realised that Pluto's orbit was weird, and then they discovered a lot of things similar to Pluto that were near Pluto, which is one of the reasons why Pluto got demoted as well (I'm sorry to the internet who still haven't recovered from that news). All of those things have very strange orbits as well, so the idea is that there could be another very massive planet, 30 times the mass of the earth something like that, beyond the orbit of Neptune, that's shepherding all these things into these weird orbits. We haven't found anything, so it could be that it's so far away that it's so faint that we can't spot it. But, there was a paper that came out a few years ago that was suggested maybe we can't see it, maybe we can't find it because it's a black hole, and that's why. It would be a black hole that would be about the size of a tennis ball, but it would be 30 times as heavy as the earth, just to give you an idea of the density of black holes. The idea that the solar system could have this just like pet black hole that's just lurking around on the edges just makes me so happy. Dog might be a man's best friend, but a black hole in the solar system is a woman's best friend in my opinion.

23:57 - How can lizards survive hurricanes?

How can lizards survive hurricanes?

Thor Hanson, Science author

Julia Ravey sits down with biologist & author Thor Hanson, to find the answers behind how animals have adapted to survive extreme weather conditions...

Julia - We are all trying to make adaptations in our own lives to climate change, and while we think about the threat to species, we often don't think about how animal populations are being altered by these extremes. Thor, in the face of extreme weathers, like hurricanes, how have certain animals adapted?

Thor - That is a marvellous question, and there's a really cool answer to it. This story comes to us from the Turks and Caicos islands in the Caribbean, and from an herpetologist named Colin Donahue, who was down there a few years ago studying these little anole lizards. An anole is a small lizard that's a distant cousin to an iguana. The idea behind this study was to go out and measure all of these lizards, and then they were going to remove non-native rats from the island and see how the lizard population responded. So, he had been out there with his team and they had caught a bunch of lizards and done all of these measurements, and then they went back to their respective universities. Two weeks later, two massive hurricanes swept across the Turks Caicos islands back to back. Category four, category five storms; winds reaching 175 miles per hour. Huge storms that flattened the vegetation and uprooted trees. The damage was so severe that the rat project was put on an indefinite hold, but Colin realised that he was in a rare position to study something else. He could go back and study the effects of the hurricanes: had any lizards survived and, if they had, was the post hurricane population different from the population that he had just measured a few weeks before. So, he cobbled together some funding and they all went back down there and found themselves in a scientific deja vu - repeating the exact same experiment they had just done six weeks earlier. They learnt that the population was measurably different. The survivors of the storm were the lizards that had larger toe pads and strong front legs, which made a certain amount of sense intuitively. If you are stuck in this windstorm, trying to hold on, big sticky toe pads and strong legs would make sense. But, they also had measurably shorter back legs, and that was a total mystery to Colin. Luckily, he had planned ahead for mysteries and had travelled down there with a leaf blower in his luggage. He told me he had quite a conversation with the customs officer trying to explain why he was travelling with landscaping equipment for a scientific project, but he needed the leaf blower because he wanted to see how lizards behaved in hurricane force winds, and you can't be standing out there in a hurricane taking notes. So, instead, he recreated a hurricane using a leaf blower on the porch of his hotel room and videotaped these lizards and their behavior. He learned that, in fact, they do hold on with those big toe pads and those strong front legs, but as the wind speed increases, their back legs begin to slip off until finally their entire body is flapping like a flag in the wind. Those short back legs give the lizards an advantage because they reduce the amount of drag on their bodies and they allow them to cling to the sticks just a little bit bit longer. That can be the difference in that severe weather event between life and death or between perishing and survival of the fittest. He realised that what he had measured in that short span of time was not just some behavioral change or some plasticity giving the lizards the chance to adapt immediately. No, he had actually measured a small evolutionary step in action: natural selection playing out over the course of a single field season.

Julia - Wow. I love the fact he took a leafblower with him and was like, "I'm gonna set up my own hurricane." This is why I love science.

Becky - It's the hotel room for me. What did he do? Put the 'do not disturb' sign out while he's there on the balcony?

Thor - I wonder what the people in the next room thought. It's one thing if someone has the TV on loud, but they're in there all day with a leaf blower!

Julia - You'd be like, "what is going on next door?" That is absolutely amazing.

30:18 - February Quiz: New Beginnings

February Quiz: New Beginnings

Becky Smethurst, University of Oxford, Greger Larson, University of Oxford, Olivia Remes, University of Cambridge, & Thor Hanson, Science Author

It's that time in the show where we put our experts knowledge to the test and in honor of it still being near-ish to the new year, - I'm still writing 2021 as the date, that's my marker - the theme for this quiz is 'new beginnings'. Becky and Greger are team one, and Thor and Olivia are team two. This is a multiple choice quiz, and conferring is allowed within teams, but there's no cross team collaboration. So let's see who is going to be the 'new-year-new-me' champion...

Julia - Round one is called 'nature awakens', and this first question is for Becky and Greger. As we speak some animal species are in the depths of hibernation, getting through the cold darkness by slowing down or sleeping (and I wish I could do the same to be honest).Groundhogs - famously used to predict the weather - can sleep for up to five months each winter. Their physiology slows down, including their heart rate, which is normally between 80 to 100 beats per minute. How often does a groundhogs heart beat when it is hibernating? Is it (A) 50 to 60 beats per minute, (B) 20 to 30 beats per minute, or (C) 5 to 10 beats per minute?

Becky - Oh, I was thinking that was lower than A. I was thinking around 10, but I was trying to work out if that was a reasonable, like 10 per minute - that's one, every six seconds. That seems reasonable for a small animal. Right?

Greger - That's my resting heart rate. So that's probably good.

Julia - And the answer is (C) 5 - 10 beats per minute

Greger - Trust your gut.

Julia - Yes, exactly. And their body temperature also drops from 37 degrees Celsius to 2 degrees Celsius, and breathing rate goes down from 16 breaths per minute to just two. So they are very much switched off from the world, which we all probably wish we could do in winter at some point. Question two - Olivia and Thor, we're over to you. A class of flies called periodical cicadas found in north America, mature in the ground for a very long time before coming out into the open for mating. 2021 saw one of these awakenings from a group called brood 10, but when will they next awaken? Will it be (A) 2028, (B) 2038 or (C) 2048?

Greger - Can we chime in and steal their point?

Julia - You definitely can't! No cross team collaboration.

Becky - Thor's already smiling like he knows the answer anyway.

Julia - People in north America, you've got an up here.

Thor - I would say that, in our parts here, you just threw that ball right over the plate. In baseball, we would hit that for a home run. Olivia, I think these are the 17 year cicadas. So that, with my math, would put us at 2038. What do you think?

Olivia - I say, let's go with that.

Julia - And the answer is, of course it's (B) - we've got people from north America here, they're going to know! Periodical cicadas come out of the ground every 13 or 17 years with brood 10's next projected emergence being 2038. And it's still unclear why periodical cicadas wait this long to come out to the surface. It's been theorized that they're high numbers all at once might saturate predators, or they might come out when bird numbers are lower. So it's still a bit of a mystery why they wait so long. But when they come out, it's very noisy I've heard, right?

Thor - Absolutely. They're extremely noisy in their vast numbers.

Julia - All emerging at once, like a big party. So at the end of round one, it's even - one, one. We're going into round two fresh. Round two is called 'birth of the universe' - Becky, you'll be hopefully liking this round. Question one, Becky and Greger. It is thought that planet earth was born around 4.5 billion years ago from a series of, collisions. But how many years after this, did it take for the first signs of life to appear?

Greger - If we guess before we get the multiple choice, do we get bonus points? Just looking for an edge.

Julia - Well, I haven't got the terms and conditions here, so I'll give you the choices, but you can be quick to the mark. I'm sure you will be. So (A) is 500 million years after the 4.5 billion, (B) 800 million years or (C) 1 billion years?

Greger - I mean, I think it's a billion. Three and a half billion. Right?

Julia - The answer is I've got B

Greger - No!

Julia - It said the first signs of life, which were thought to be microscopic organisms, existed 3.7 billion years ago. They were found in rocks that were marked 3.7 billion years old.

Becky - It's just rude.

Greger - And I don't know - the confidence intervals on that dating,I think it's probably 3.5.

Julia - What's the difference? 3.5? 3.7? Same thing. So we just missed that one, but I love the confidence. Question two, we're coming over to Thor and Olivia. When a star is born (not in the Hercules kind of way) clouds of hydrogen called nebulae interact together, producing clumps which heat to 10 million degrees Celsius. Once this high temperature is reached inside a young stellar object, nuclear fusion - the joining two nuclei to make a new atom - transitions it into stardom, with hydrogen atoms fusing to become helium. What element inside a star signals its most near to the end of its lifespan? Is it (A) carbon, (B) magnesium, or (C) iron?

Thor - Olivia, I don't know. We can't ask Becky this question?

Greger - Yes we can!

Julia - I'll ask Becky at the end to probably clarify on the answer for us.

Olivia - I don't know why, but I'm tempted to say carbon, what do you?

Thor - I'm with you a hundred percent. That was my gut reaction too, which is not based on much, but we'll go for it.

Julia - Well, the answer is (C) iron!

Greger - So it's the heavier stuff.

Julia - Yes. When atoms fuse within a star to eventually form iron, this creates an inert core and it doesn't release energy for the star to keep burning and leads to stellar death. Becky, what happens when a star dies?

Becky - Essentially, what happens when you hit iron is that you have to put more energy in to fuse iron together than you get out from nuclear fusion, so there's just nowhere for the star to go at that point. And so when the star dies, essentially there's no force pushing outwards against the gravity pulling inwards and you get this collapse inwards.

Julia - There you go - answered by the expert on that one. We don't want iron at the core of the star. That's not a good sign. So at the end of that round, we're still on one, one - nothing lost nothing gained going into the final round now, which is called 'humans and habits'. Becky and Greger question one is for you. It's thought the human brain is made up of about 86 billion neurons and these cells do not divide. However, in the 1990s stem cells were found in the brain with one pool located in the region important for forming new memories called the hippocampus. But how many of these new neurons are thought to be born each day in an adult human brain? Is the answer (A) 700, (B) 2,700 or (C) 27,000?

Becky - I don't like the neuroscientists, they're the only ones that can give us a run for our money with the big numbers. I feel like for them to put such a small number in there, it has to be quite small?

Greger - This is about as far away from either you or me as possible. Right?

Becky - So do we just go right down the middle?

Greger - Ooh, not a bad idea. 2,700?

Julia - The answer is (A) - Becky, you were close! Based on the data using C14 carbon dating, which essentially time tags DNA due to different levels of C 14 in the atmosphere, it's thought 700 new neurons are added to this part of the brain each day. And that represents a turnover of about 1.75% per year in this little section of the brain. And this is drastically smaller to say our blood cell turnover, where millions of new cells are produced on the daily. Question two, Olivia and Thor - you could steal this here. At new year's, many people set new year's resolutions to signal a new beginning in terms of changing their behaviors. A large study of 60,000 people looking at prompting, showing up to the gym consistently found which method to be most effective? Was it (A) setting a plan in advance of when and where the people would workout, (B) giving people an incentive to return to the gym after they'd missed a workout or (C) signing an exercise commitment pledge?

Olivia - I would go with (A) setting a time and place to go and do the exercise. What do you think?

Thor - I would go with that too. If you're setting a time and place, and making a plan and coordinating with others, you've made a commitment by gosh.

Julia - The answer is - B!

Olivia - What? No!

Julia - This study was published in December, 2021. And it found that while various methods of planning, reminders and incentives to keep working out did work, rewarding people for going back to the gym after they'd missed a workout came out as the best for increasing the number of gym visits and maintaining this change after the study finished. So that means that we're on a tie break and we do have a tie break question. Of course, in these instances, we have a tie break. Our intern who wrote the tie break, didn't hear me correctly when I said the quiz was called 'new beginnings' - they heard me call it 'new innings'. So the tiebreak question is in the 2021-2022 Ashes series, how many runs did England score across all five tests against Australia? So this is a ballpark - whoever gets closest to the number of runs that England got, they claim victory.

Greger - 2000.

Julia - Okay. So Greger is thinking 2000. Becky, you going with that?

Becky - Oh, we have to say The same - Yes, I would've gone 1600, like 400 times four.

Greger - There were five tests though.

Becky - Oh, there's five tests. Not four. Yeah, so 2,000.

Olivia - Gosh, I don't know.

Thor - We'll do the sleazeball move here and add one to yours.

Greger - The price is right manoeuvre.

Thor - That's exactly right!

Becky - You would assume England did better than we think they did.

Julia - So we've got a 2000 versus a 2001. The answer is 1,913 - Becky and Greger stole it at the last minute! That's how many England got. Australia, this time got 2,554, which led to a 4-0 victory for the Aussies. At the end of the quiz, that means we have champion Supreme, Becky and Greger - team Oxford - have won!

Greger - Can we pause this so I can tweet that right now? Just play claim to that victory.

Julia - Claim the victory!

41:44 - How to beat procrastination

How to beat procrastination

Olivia Remes, University of Cambridge

When we take on a big project, we often find ourselves raring to go. We get a plan together. We buy the new stationary, get a new diary. But when it comes to actually doing the project, we stall. We asked Olivia Remes from the University of Cambridge why we procrastinate and how to stop the loop of procrastinating and worrying about work so procrastinating more...

Olivia - Procrastination comes from the Latin word 'procrastinari', which means 'putting off until tomorrow'. Basically it's this needless delay, even though we know that it's in our best interest to act now, and there are some strategies for helping you to overcome procrastination. One of the strategies to tackle procrastination is to simply practice tolerating that initial discomfort. Sometimes when we sit down to work and we have a task in front of us, we may be having feelings or experiencing feelings like bored, frustration, whatever negative feelings you're experiencing, just to notice them and learn to tolerate them. Our impulse might be to try to get away from these feelings to get away from the boredom, to get away from the frustration, we want to run away from the task at hand. But simply practice tolerating these initial feelings of discomfort, and they will go away because these feelings are transitory. Another great strategy is to choose to tap into a positive emotion. All of us at any given time have a landscape of rich emotions that we can tap into, like curiosity - so being curious about a task. Tap into one of those positive emotions when you are working on your task and this will make it much easier to get going and to stick with it. And finally, another strategy that you can use to help you to overcome delayed procrastination is to do badly.

Julia - I love that. I always do a draft zero of everything that I do and no one ever sees it except for me. And it just gets me started.

Becky - I found that just redefining what you mean by a draft really helped. Like a draft to me at first was like something that I could share with other people. And I realised, no, that's not what a draft is. A draft to me is like word vomit on a page and then I can finally do something.

Julia - Exactly. I just get it out of your system and then it's like, I can then sort that later, but just getting over that barrier to start, I think is so important.

44:24 - Did we unintentionally domesticate animals?

Did we unintentionally domesticate animals?

Greger Larson, University of Oxford

An article was published recently suggesting that when it comes to sheep and goats in a region of Turkey, humans may not have intentionally meant to domesticate these animals. So have we ended up now with animals that we didn't maybe mean to have domesticated...

Greger - Yes. I think that there's this idea that we're not terribly humble as a species. We tend to be very self-motivated and we tend to think of ourselves on the up of whatever thing that we're categorising. And as a result of that, when we look to the past, we tend to have this very interesting perspective, which assumes that everything had a reason or a purpose of getting there and that we were always acting in a very intelligent fashion in order to get to where we are now, which was a very good idea at the start of everything. And this presentist perspective is a bias that really undermines what was actually happening throughout tons of history, which is full of nothing really, but accident and happenstance and opportunity. So there's a really cool idea that some colleagues of mine put out a few years ago where they referred to these things in as labor traps. Rather than this kind of presentist perspective, where it's like we started domesticating plants because we knew it would be good for us and we wanted larger seeds and we spent more time focusing on just a small handful of things. Instead, they were like, once you start investing in things, you then become more reliant upon it. And what happens is there's this whole really interesting trajectory which starts off - and you can apply this to just about every aspect of your life. When you first encounter something, you're often kind of wary of it. Then you become accustomed to it, but you don't really pay that much attention to it. Then you start becoming a little bit more reliant upon it. And after a little, while you become wholly dependent upon it completely. And that's probably true of the relationship that you're in right now, or your relationship with any food stuffs that you eat, or what your exercise as routine or anything else. And this is probably the same trajectory that was taking place with a lot of early domestic plants and animals as well, where initially at the site that you're talking about called Aşıklı Höyük in Turkey, where at the very bottom layers, you see people who were taking advantage of a wide range of different resources from a huge catchment area around the site. And then through time, there becomes this increasing reliance on a small handful of sheep and goat. And that process took 300-500 years. It's not like somebody looked multiple generations in the future and said, "we want to only be exclusively eating sheep and goat and we think that that's gonna be the best thing for humanity going forward", because those kinds of decisions aren't operating on the sorts of time scales that are visible within the archeological record. I think we are better served by looking at these processes in a much more accidental and happenstance rather than always assuming that we were making brilliant decisions as a species all the way back and we can look back at our ancestors and go "well done, we really love this peanut butter and jelly sandwich."

Julia - Yes, the brain has very much a present bias as well - we're not really thinking years down the line. It's like, what could I do right now? It wouldn't have been priority to think years down the line. You're thinking when's my next meal going to happen. And that relationship together probably led to a lot of the domesticated, as we say, animals that we have today.

Greger - Exactly.

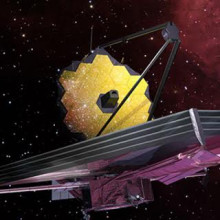

48:40 - How does the James Webb telescope work?

How does the James Webb telescope work?

Becky Smethurst, University of Oxford

As we record this episode, the 10 billion dollar James Webb telescope is moving towards its final destination. We asked astrophysicist Becky Smethurst what we are hoping to see with this telescope, and whether it might be able to tell us a bit more about potential other life forms in the universe…

Becky - 100%. It's one of the main science goals of the James Webb space telescope - or JWST as we call it. So what James Webb has been designed to do is look at infrared light. And this is the key thing with James Webb and why it needs to be so far away and have a giant tennis-court sized sun shield to protect it from infrared light from the sun. But what it'll be able to do is see stuff that the Hubble space telescope physically can't see because it looks at visible light. And the thing is, the light from the very furthest stars and galaxies away from us, the light that was emitted at the very beginning of the universe and is currently still traveling towards us, has been redshifted by the expansion of the universe. So space is expanding and it essentially drags out the light wave as it goes and stretches it along the wavelengths, which are redder. But this has been stretched out so much that when it was emitted as visible light, it is now infrared light. So Hubble has no chance of seeing it at all. It can't even pick it up. It's not that it's just faint, it can't detect it. So this is what James Webb has been designed to do, is to see the light from the first stars and galaxies that there ever was in the universe, essentially to detect the oldest light that is. And so that's what I'm really excited for. It also might answer sort of like a chicken or an egg question - whether the first stars form, make a black hole, and then that become the first super massive black hole that happened to then fall and sink to the centre of a galaxy, because it was the heaviest thing. Or did a super massive black hole collapse from the first gas in the universe and then a galaxy of stars form around it. But then the other thing that the JWST can do because it works in the infrared, is look at the fingerprints of different molecules in terms of the light they absorb or emit. A lot of the key ones for life are in the infrared; water specifically leaves a fingerprint on infrared light so that we know that it's there. So the plan is, for what we call exoplanets, planets that orbit other stars in our galaxy, when they pass in front of the star that they orbit, we can take the tiny amount of starlight that happened to pass through the skinny bit of atmosphere around them, isolate it and work out what molecules are present in that atmosphere and whether water is present there and other indicators of life biomarkers, biosignatures as we call them. We could be in a position in five years time, where we find the most habitable place for life that we've ever seen beyond earth.

Julia - That's pretty cool!

51:40 - What couldn't we eat without bees?

What couldn't we eat without bees?

Thor Hanson, Science Author

Over the past few years, there has been a buzz about saving the bees. These insects are under threat due to disease, climate change and habitat loss. Thor Hanson, science author, tells us why bees are so important and why they need saving…

Thor - We rely upon bees for so much more than we think because they are so essential to the pollination systems that fuel wild plants, as well as crop plants. Probably the most famous statistic that people use about bees and our reliance upon them is that one out of every three bites of the food that we eat is reliant, at some stage, upon bees for pollination. And that's a great statistic, but it doesn't really tell us all that much about what kinds of food they give us or what food would be like if we didn't have bees. And one of the ways that you can get this across is to go and try to have a meal that involves no bees. So I conducted a little experiment once myself with a very famous recipe, the McDonald's big Mac hamburger. I went to a McDonald's shop, ordered one of these famous double cheeseburger sandwiches, and then dissected and removed all of the ingredients of the big Mac that relied upon bees for pollination. After I took all the sesame seeds off the bun and took off the pepper, pickles, tomatoes, lettuce and the sauces and so forth, and separated everything out, I realised I could still have the two, all-beef patties in the sandwich because the cows could have been fed solely upon grasses, and I could have the buns without the sesame seeds, because the buns themselves were from grains, which are wind-pollinated grasses. But pretty much everything else on that sandwich, including everything that made the food interesting or flavourful was a product at some point of bee pollination. What I learned from that experiment was that, yes, we could still eat something in a world without bees, but our food would be extremely dull, less nutritious, and we'd have to just eat what we could.

Julia - And there'd be no big Macs. So that is a lesson to us all. Well, there wouldn't be salad, which is probably the healthy part of that as well. Take off all the health and that's what you're left with. No, we've gotta save the bees, right?

54:28 - Quick fire questions

Quick fire questions

Becky Smethurst, University of Oxford, Greger Larson, University of Oxford, Olivia Remes, University of Cambridge, & Thor Hanson, Science Author

Time for a quick fire round now, one question each for our panel of experts including an insight into motivation, what would happen if you put Saturn in a bathtub and why we have an easter bunny…

Julia - Olivia, we had a question in from Naomi about motivation who asked, why can we feel motivated to do something like a social activity, but not a work activity? So feel motivated to see our friends, but not doing work? What's the difference?

Olivia - It could be the difference in pleasure levels between the two. So when we're thinking about meeting our friends and going out somewhere fun, then of course that's an enjoyable activity. You like to do that. But sometimes with tasks that we may have to do in life, some can be more difficult and time consuming than others. So again, it comes back to those unpleasant emotions that we're feeling and hence the lack of motivation possibly.

Julia - Greger, animals are a huge symbol in many traditions and celebrations, and we don't even question them being there, but why do we have an Easter bunny?

Greger - My favourite bit about the Easter bunny is that the tradition of Easter starts in Germany, comes over to the UK, but is associated with hares, so it was the Easter hare to start, and the hares, as were also European, were introduced to the UK. Then the hare gets replaced by the rabbit, for reasons we're actually working on right now, trying to work out when and how that happened, and the rabbit takes over and becomes part of this indelible part of the whole Easter tradition, which also includes chickens, which have nothing to do with the UK either. So everything we know about Easter in the UK has nothing actually whatsoever to do with the UK, but it's all been component parts which have been pulled from everywhere else. It's great.

Julia - And we are claiming the tradition is ours but it's definitely not. Becky, you wrote a book, “Space - 10 things you should know”, what is your favourite bite of space knowledge you think we all should know?

Becky - I'm gonna go for one that has stuck with me since I was eight years old and possibly was the reason I became an astrophysicist. And that is, if you could find a tank of water or ocean big enough Saturn would float because its density is less than water. That and Saturn's my favourite planet by far.

Julia - That is amazing. That visual, I'm seeing like a huge bathtub with Saturn on the top. And finally, Thor over to you, you wrote a book all about how seeds conquered the planet, which seed has the most fascinating method of dispersal?

Thor - It is hard to narrow it down to a favourite, but the seed of the Javan cucumber, which was well known long before anyone figured out what plant it was coming from because the seed travels so far. The design of the seed is such that it actually led to an aircraft design that is now the basis for the stealth bomber, one of the most dangerous things humans have ever come up with, this single winged aircraft. The Javan cucumber also has a single wing, this thin, filmy membrane around the seed that stretches out and allows it to drift upon the slightest breeze for kilometers. And so sailing ships going through the Southeastern Asian archipelagos would have these seeds dropping upon the ships now and then. They knew all about the seed long before anyone ever realized that they were coming from these particular plants hidden up in the rainforest canopy, these lianas up there that were dropping these seeds out into the wind. So the seed travels so far that people knew about the seed before they knew about the plant.

Julia - Wow. That is a reputation. That is an absolute reputation.

58:07 - What is February's mystery sound?

What is February's mystery sound?

A panther meowing.

Becky - It was a cat!

Julia - It was a cat! They're the largest of the lesser cats, so they can meow and purr. They're the mascot for the Carolina Panthers in the NFL, who are the fourth in the league and their song is called ‘On the rise’, and also the Nottingham Panthers ice hockey team. Panthers like to swim and they can sprint up to 50 miles an hour, but their steady pace is about 10 miles an hour. So that would make the 65 mile trip from Cambridge to London take a pretty long time.

Related Content

- Previous Trees for the Jubilee

- Next Black hole seen forming new stars

Comments

Add a comment