Come with us on a tour of your body to discover how the bacteria that live on and in you play an important role!& Bad breath bacteria, good gut bugs and the ones that escape through the other end all make an appearance, as we find out how bacteria are essential to your health and how probiotics could prevent or even treat asthma and allergies.& Plus, we find out how clot busting drugs could treat brain haemorrhages, why pilot whales are the cheetahs of the sea and how a robot could give you a full head of hair.& Plus, in a smelly kitchen science we ask if coughs and sneezes can spread diseases, then what about flatulence?

In this episode

- Can stifling a sneeze do you damage?

Can stifling a sneeze do you damage?

There's no connection between the bit of the respiratory tree that the sneeze has to rush out at 100kph at your brain. I think if you don't let the sneeze out there's a possibility you could end up with the mucus it's trying to dislodge being rammed further into the passages inside the nose, the sinuses for example. You could actually encourage the build-up of mucus which could be laden with infection. You could encourage infection so it's probably better to let it out. There's nothing better than a sneeze, is there?

A stroke of luck for brain bleed therapy

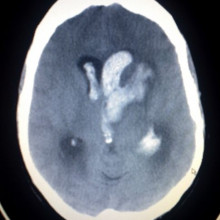

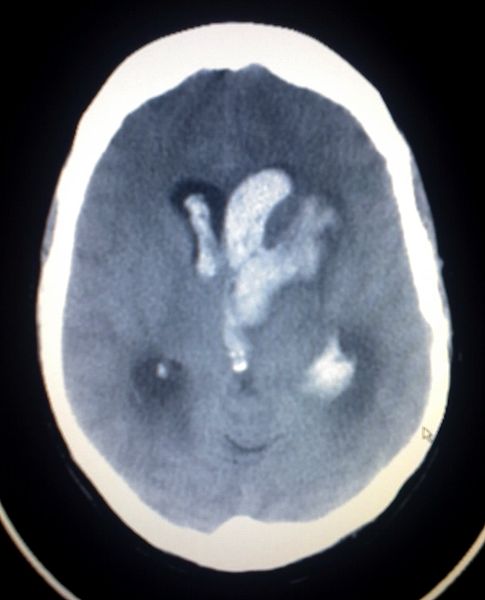

Doctors may have found a way to dramatically improve survival rates for patients suffering from brain haemorrhages.

Daniel Hanley and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins have taken the bold step of infusing a clot-dissolving agent called tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) into the heads of 52 patients who had suffered bleeding into their brain tissue. "We've gone from what's usually an 80% death rate in patients with this condition to an 80% survival rate," says Hanley.

Daniel Hanley and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins have taken the bold step of infusing a clot-dissolving agent called tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) into the heads of 52 patients who had suffered bleeding into their brain tissue. "We've gone from what's usually an 80% death rate in patients with this condition to an 80% survival rate," says Hanley.

Drugs like tPA are usually avoided in conditions that involve bleeding for fear that they might exacerbate the problem, but the Hopkins team set out to investigate whether very low doses, administered not into the blood stream but directly into the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the brain, might be a safe way to tackle the problem of brain haemorrhage.

Bleeds into the brain are so often fatal because the blood forms clots inside the fluid spaces, called ventricles, inside the brain, impeding the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and causing swelling. This, in turn, applies dangerous pressure to the brain, whilst other factors also present in the blood trigger blood vessels to go into spasm, which can further compound the damage. Dissolving the clot is therefore a priority, but difficult to achieve safely.

In the trial the patients were given one of three different doses of tPA every 12 hours and followed up using daily CT scans. On average the patients receiving the highest dose of the drug cleared their blood clots three times faster than patients who received just supportive care, and about a day faster than the patients receiving the two lower tPA doses.

Reassuringly, the patients on the clot-busters were no more likely to suffer additional bleeding than supportively-managed cases. One month post-treatment more than 80% of the treated patients were still alive and 10% of them had even managed to return to work. The team now plan to set up a much larger trial involving 500 patients to test the benefits of their approach more stringently, although they are highly optimistic about the results.

"We think that this treatment is the most promising story in brain haemorrhage in many years," says Hanley. "We've taken a condition that used to have an extremely high death rate and disability and turned it around."

Female Croakers - Noisy Frogs are not always the Men

Of all the members of the frog world, it has always been thought that the noisiest croakers are the males, who sing out to attract mates.

But now it seems that female frogs may occasionally do the same thing. Just before they are about to lay their eggs, female concave eared torrent frogs from the Huangshan Hot Springs in central China, call out with an ultrasonic peep to attract a male to come and fertilise them.

But now it seems that female frogs may occasionally do the same thing. Just before they are about to lay their eggs, female concave eared torrent frogs from the Huangshan Hot Springs in central China, call out with an ultrasonic peep to attract a male to come and fertilise them.

That's what a team of researchers led by Jun-Xian Shen from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing found out when they took some of these frogs into the laboratory.

They already suspected that the females had the ability to call, because when they dissected one, they discovered well developed vocal chords - something that most female frogs don't have.

And when they listened to the frogs with ultra-sonic detectors, they did indeed hear the females calling out when it was time to lay.

The team recorded these calls and played them back to males who responded immediately by hopping directly towards the source of the sound, sometimes in a single, well-aimed leap.

It is thought the females shriek at such a high pitch so they can be heard over the noisy babbling of the streams they live next to. And this puts these frogs among a small group of animals that communicate with ultra sound including bats, whales, dolphins and some insects.

And as well as telling us more about the wonderful goings on in the natural world, these findings may also have implications for studies of human hearing. By understanding more about how these frogs can so accurately detect and locate the source of particular calls may help scientists design more effective hearing aids for people.

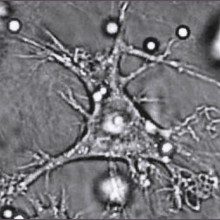

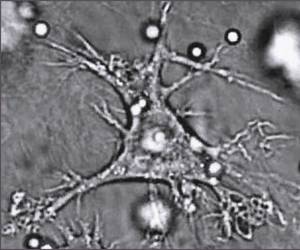

Scientists uncover HIV's Hideaway

Scientists have discovered where HIV hides out in the body, highlighting an important target for future therapies and solving a long-standing puzzle about where the virus goes even when levels in the blood fall to undetectable levels.

Writing in this month's Journal of Virology, Brigham Young University researcher Greg Burton and his colleagues studied tissue samples from AIDS patients and showed that one of the immune system's key orchestrators, the follicular dendritic cell (FDC), which has the job of presenting foreign material to the other components of the immune system, can hang on to intact HIV particles and keep them intact for months if not years. By binding onto the virus particles in this way the FDCs paradoxically protect and preserve the virus in an infectious form which can subsequently re-infect other vulnerable cell types when they pass by.

Writing in this month's Journal of Virology, Brigham Young University researcher Greg Burton and his colleagues studied tissue samples from AIDS patients and showed that one of the immune system's key orchestrators, the follicular dendritic cell (FDC), which has the job of presenting foreign material to the other components of the immune system, can hang on to intact HIV particles and keep them intact for months if not years. By binding onto the virus particles in this way the FDCs paradoxically protect and preserve the virus in an infectious form which can subsequently re-infect other vulnerable cell types when they pass by.

By testing samples collected from patients over an extended period of time the team were able to compare the genetic sequences of viruses harboured by their FDCs when they died, with viruses that were present at different times during their illnesses. The results show that the cells are effectively archiving samples of the patient's viruses over an extended time period, which has important implications for future treatments designed to flush HIV out of the bodies of infected individuals.

So why should these cells do something so apparently self-destructive? The team think that FDCs store samples of what is challenging the body in order to enable them to regularly remind the immune system what it needs to respond to. When we're vaccinated, for instance, the material in the vaccine is probably dispensed a small amount at a time, to help to maintain a robust and long-lasting immune response. Unfortunately, HIV has evolved a strategy to exploit this immunological loophole and turn it to its own advantage. "If we could go in and perhaps flush it from the surface of the cells, we might decrease dramatically the amount of virus that could perpetuate infection," says Burton.

Speedy whales - the Cheetas of the Sea

When they are hunting, pilot whales may sprint after their prey in incredible bursts of speed in the dark depths of ocean, just like speedy cheetahs do on land.

That's according to Natacha Aguilar Soto from La Laguna University in Spain, and colleagues from Woods Hole in the US and Aarhus University in Denmark who have been studying pilot whales off the coast of the Canary Islands in the Atlantic.

That's according to Natacha Aguilar Soto from La Laguna University in Spain, and colleagues from Woods Hole in the US and Aarhus University in Denmark who have been studying pilot whales off the coast of the Canary Islands in the Atlantic.

Studying the foraging behaviour of deep sea creatures like whales is obviously a huge challenge. So to find out more about how whales catch they food, this team attached electronic tags to 23 pilot whales to record how fast they were swimming, how deep they swam and in which direction, as well as any noises they emit while looking for prey.

What the researchers have discovered is that far from being energy-saving slow-swimmers, pilot whales can swim incredibly fast. They can plunge down to a kilometre in just fifteen minutes, and it seems, just like a cheetah, when they spot prey they will dash after it in a sustained burst of speed.

Cheetahs can sprint over short distances at about 60 miles an hour, which whales don't quite top. But they do speed up to 9 metres per second, or around 20 miles an hour, and keep it up for 200 metres before either catching the prey or giving up.

And we know that they are feeding because of the noises they make. Like bats in the air, whales use sonar to locate their prey, and as they home in on a tasty morsel they send a barrage of hi pitched clicks to help pinpoint its location.

All this deep sea speed comes as quite a surprise because scientists previously expected that whales would try to save oxygen by swimming slower for longer. But now it seems their behaviour might be better suited for sprinting after fast-moving prey like the incredible giant squid that has recently been thawed in New Zealand.

Hairway to Heaven - A hair-restoring robot.

Researchers have developed a hair-restoring robot. New Scientist reports this week that a team from Restoration Robots (RR), in California, have developed a way to speed up hair transplants.

At present, comb-over kings are required to endure ten hours of painstaking surgery during which, initially, a strip of hairy scalp about 1cm wide and 15cm long is removed, the edges of the donor site sutured together and then the hair follicles from the strip are separated out and planted into hair-sparse areas.

At present, comb-over kings are required to endure ten hours of painstaking surgery during which, initially, a strip of hairy scalp about 1cm wide and 15cm long is removed, the edges of the donor site sutured together and then the hair follicles from the strip are separated out and planted into hair-sparse areas.

Restoration Robot's strategy is different. Their automated system takes just 5 hours to do the job and rather than working from a strip of excised scalp their robot harvests individual hair follices, which are first identified using 3D imaging software and then collected one at a time using a 1mm hollow bore needle. Once the harvest is complete the patient sits up and the machine begins the process of systematically re-implanting the clutch of follicles to produce an acceptable Barnet.

The system is currently being tested on volunteers in California, so if a friend suddenly sprouts a shock of new hair you can assume they've been for some "RnR" in Mountain View, California...

Can you keep your eyes open when you sneeze?

Chris: I've kept my eyes open in the name of objective research, whilst sneezing, to see what would happen. I can categorically say I still have my eyes, I can still see so I don't believe the idea that they pop out.Helen: I don't know. I've tried and failed to keep my eyes open. I just can't do it. How do you do manage?Chris: I just forced myself. I was driving and I didn't want to shut my eyes so I couldn't see. I forced them to stay open and I still have my eyes. I don't know where this myth comes from but the fact is that the only connection between the nose cavity and they eye is in your tear duct which runs from the edge of your nose up to the middle part inner surface of your eyelids. If you look at your lower eyelid, right where it meets the edge of your nose you'll see a little black dot. That's the plughole through which tears drain. I think the reason we close our eyes when we sneeze is probably because you do get quite a big build-up of pressure in the nose. It will cause a sort of reflux of fluid back up the tear duct and it will squirt your tears back into your eyes. If you screw your eye up you squeeze that duct closed and it does stop some of the tear from squirting back into your eyes. That's why people say blow your nose if you have something in your eye because it forces some of the tears back up into your eye. It means that there are more tears in the eye for a short while. This helps to wash out everything. I don't believe sneezing makes your eyes pop out.

16:54 - Bacteria and Bad Breath

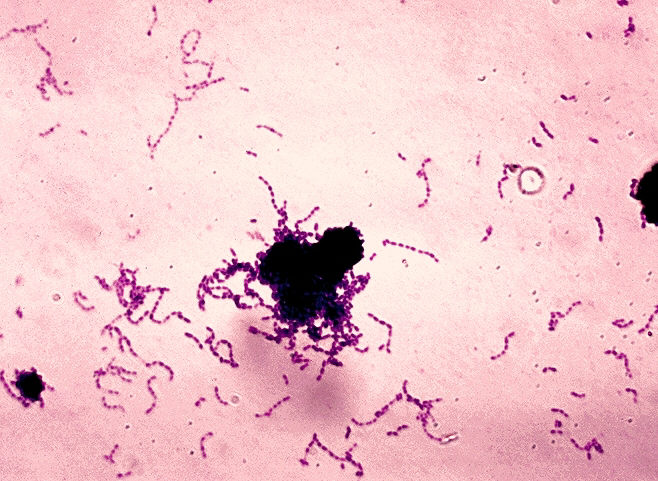

Bacteria and Bad Breath

with Marcello Riggio, Glasgow University

Helen - Marcello Riggio from the University of Glasgow has been studying the bacteria of the mouth. Hello Marcello.

Marcello - Hello, good evening.

Helen - Thanks for joining us on the show today. What sort of bacteria do we find living in the average mouth?

Marcello - The mouth is composed of many, many hundreds of bacteria: each with different properties. At the last count there were approximately 700 species that had been identified. However, only about half of those can actually be physically grown in the laboratory. It's a really diverse population of bacteria within the mouth. Obviously we have a number of good bacteria which will promote good oral health and unfortunately we have a number of bad bacteria which are involved in some nasty oral diseases.

Marcello - The mouth is composed of many, many hundreds of bacteria: each with different properties. At the last count there were approximately 700 species that had been identified. However, only about half of those can actually be physically grown in the laboratory. It's a really diverse population of bacteria within the mouth. Obviously we have a number of good bacteria which will promote good oral health and unfortunately we have a number of bad bacteria which are involved in some nasty oral diseases.

Chris - What sort of densities do you find these bacteria in, Marcello, if you were to take a swab from the mouth? People talk about a table-top: on each square centimetre of some desks 20,000 bacteria per square centimetre. What would be the numbers that you would get from the mouth?

Marcello - It depends on which part of the mouth you were actually looking at. The tongue which is the area of the mouth which harbours bacteria, which cause bad breath, has a very dense population of bacteria. You're really talking in terms of millions of bacteria in a small surface area. It really is bacterial-rich environment.

Chris - It's a bacterial banquet.

Marcello - Yes!

Chris - Why do we have them there? Is it purely because we can't do without them, is it because we can't stop them being there or is it because they actually do something useful?

Marcello - First of all, we can't stop them being there. Bacteria are present throughout the human body so the mouth isn't any different from the rest of the body. There are a number of bacteria which have been identified. One in particular, which is certainly classified as a good bacterium that people have found is present in higher levels in a healthy mouth compared to somebody who's got bad breath for example. The good bacteria are there to swamp out the bad bacteria to keep it in simple terms.

Chris - What about tooth decay? Is that down to the same bacteria and are there therefore more people who have tooth decay-prone bacterial types in their mouths?

Marcello - The bacteria that cause tooth decay, dental caries and periodontal disease which is the disease that results in you actually losing the teeth. There are distinct bacteria associated with each of these types of diseases. If you look at dental caries, dental caries is loss of the enamel on the tooth surface. That is caused by bacteria which are very good at producing acids, particularly Streptococcus mutans and a few helper bacteria. If we look at things like periodontal disease and gingivitis, gingivitis is the swelling and bleeding of the gums, there are specific bacteria associated with that and the associated, more severe form of the disease known as periodontal disease.

Marcello - The bacteria that cause tooth decay, dental caries and periodontal disease which is the disease that results in you actually losing the teeth. There are distinct bacteria associated with each of these types of diseases. If you look at dental caries, dental caries is loss of the enamel on the tooth surface. That is caused by bacteria which are very good at producing acids, particularly Streptococcus mutans and a few helper bacteria. If we look at things like periodontal disease and gingivitis, gingivitis is the swelling and bleeding of the gums, there are specific bacteria associated with that and the associated, more severe form of the disease known as periodontal disease.

Chris - Returning to what can really be described as radioactive breath, halitosis, is that linked to bacteria in the mouth?

Marcello - Very much so. Halitosis is a term, and it comes from the Latin: halitus, meaning breath and osis, meaning awful condition. It's defined as an abnormally odorous condition of the breath. It is well documented that it is caused principally by bacteria. There are various different types of bad breath; different causes. We can have what is known as genuine halitosis which can be either physiological or pathological. Genuine halitosis, which is physiological is caused by bacteria on the rear surface of the tongue. We've done a very large study trying to identify those particular bacteria. You can also have bad breath, as I'm sure you all know, from eating smelly things in the diet. Things such as onions, garlic and other spices: that sort of bad breath is transient and disappears fairly quickly. We were more interested in our own research to look at long-term bad breath or halitosis, caused bacterial metabolism on the rear surface of the tongue.

Chris - Do you think certain people are more likely to carry the types of bacteria that give you bad breath and therefore it tends to associate with certain people? For instance, if I had a partner who tended to have smelly breath and I kissed them a lot could I then end up infecting myself with the same bacteria so I would then also get smelly breath?

Chris - Do you think certain people are more likely to carry the types of bacteria that give you bad breath and therefore it tends to associate with certain people? For instance, if I had a partner who tended to have smelly breath and I kissed them a lot could I then end up infecting myself with the same bacteria so I would then also get smelly breath?

Marcello - At the moment we're not absolutely certain which bacteria are the major culprits which cause bad breath. However, in our own study we have shown that the overall presence of bacteria in people with and without bad breath are pretty much the same. What we actually see is a change in the numbers of specific bacteria in people with bad breath compared to those who don't have bad breath. It seems to be relative amounts of bacteria are shifted in a proportion of a particular species of bacteria that causes the bad breath. In effect we all do possess the bacteria that cause the bad breath but those of us without the bad breath have them in a much lower number.

Wally Mandlebrot in Second Life commented: "I'll remember this next time I kiss someone!"

Marcello also answered these listener questions:

From Troy McLuhan, Second Life:

They say there's something called fight bite which happens when people get bitten by other people. They get a bad infection. What's that all about?

Marcello - Bacteria can easily be transmitted through bites. Bacteria in the oral cavity are designed to stay there, actually. They can get to other parts of the body and cause more serious diseases. If one were able to transmit some of these more opportunistic oral bacteria to other body sites then yes, they can cause serious infections.

From Diane:

I'd heard in the past that oral bacteria can cause heart valve problems and hip joint infections. Is this true and which bacteria are involved?

Marcello - Yes, oral bacteria can be transported around the body and the blood. If they can get into the blood stream they can be transported to various body sites and cause far more serious systemic infections. You're quite right. You mentioned two infections: endocarditis, which is an infection of the heart valves in the inner lining of the heart and hip joint infections. There are a number of bacteria that do cause endocarditis, for example. These tend to be Staphylococci and Streptococci. There are a number of other oral bacteria which have also been implicated in that. We've carried out a study looking at prosthetic hip joint infections, looking at the types of bacteria which are involved in these particular infections. We've identified a number of bacteria including bacteria which are known to reside in the mouth.

Chris - Basically you infect yourself with what you've already got in your mouth and it translocates to a bit of the body that it shouldn't?

From David, Nottingham:

The new toothbrushes that I've seen adverts for on the TV have got a sort of scraper that you're supposed to scrape along your tongue. Should we be using these things? Are they actually beneficial?

Marcello - Absolutely, the bacteria that cause bad breath are actually towards the back of the tongue and they are buried deep within the tongue. The only way to remove them or reduce their numbers there is to actually use some form of scraping device. It's not a very pleasant thing to do if you're trying to scrape bacteria from the back of the tongue. One may occasionally gag as well but if you can do that regularly it will help to keep bad breath at bay. Yes, one would definitely advocate the use of any scraping device, particularly those which are incorporated into tooth brushes. It has been shown if you can reduce the number of bacteria at the rear of the tongue then there will be less chance of you having bad breath.

From Paul, Essex:

Is there anything you can do to combat bad breath apart from a tongue scrape and a toothbrush?

Marcello - Unfortunately at the moment there is no cure or effective treatment so one should actually continue to use these scrapers where at all possible. Unfortunately there's a perception that people with bad breath have got poor oral hygiene. That is not the case. You can keep your teeth scrupulously clean and floss consistently and you will still have bad breath unfortunately. You can use zinc containing chewing gum, for example, which will help to a certain extent. There is no good solution or cure at the moment.

Chris - I did hear that swilling your mouth with hydrogen peroxide in low concentrations is also quite good at killing the bacteria.

Marcello - Yeah. There are a number of solutions such as hydrogen peroxide which will kill bacteria but one has to be careful that you're killing off the good bacteria as well as the bad bacteria. That's certainly something we don't want to do. These agents are non-selective.

From Chris, Cardiff:

Are we washing off our skin bacteria using antibacterial soap? Can we put them back perhaps with some sort of lime yoghurt?

Marcello - Yeah! It's very important to have good hand hygiene but most of the bacteria on the surface of the skin are fairly harmless unless they get into the bloodstream where they can cause nasty infections. The most well-known is MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. We don't need to worry about bacteria on the skin. They don't cause any harm so long as they stay on the surface of the skin. Skin is a very good barrier and they don't get into the bloodstream.

Chris - If you strip away the good ones is there not a danger the bad ones might take over?

Marcello - There certainly is, actually but if you've got bad bacteria on the skin then as long as they don't get into the bloodstream they're not going to cause any major problems.

What is fight bite?

We put this question to Marcello Riggio:

Bacteria can easily be transmitted through bites. Bacteria in the oral cavity are designed to stay there, actually. They can get to other parts of the body and cause more serious diseases. If one were able to transmit some of these more opportunistic oral bacteria to other body sites then yes, they can cause serious infections.

Can mouth bacteria cause heart problems?

We put this question to Marcello Riggio:

Yes, oral bacteria can be transported around the body and the blood. If they can get into the blood stream they can be transported to various body sites and cause far more serious systemic infections. You're quite right. You mentioned two infections: endocarditis, which is an infection of the heart valves in the inner lining of the heart and hip joint infections. There are a number of bacteria that do cause endocarditis, for example. These tend to be Staphylococci and Streptococci. There are a number of other oral bacteria which have also been implicated in that. We've carried out a study looking at prosthetic hip joint infections, looking at the types of bacteria which are involved in these particular infections. We've identified a number of bacteria including bacteria which are known to reside in the mouth.

Do toungue scrapers work?

We put this question to Marcello Riggio:

Absolutely, the bacteria that cause bad breath are actually towards the back of the tongue and they are buried deep within the tongue. The only way to remove them or reduce their numbers there is to actually use some form of scraping device. It's not a very pleasant thing to do if you're trying to scrape bacteria from the back of the tongue. One may occasionally gag as well but if you can do that regularly it will help to keep bad breath at bay. Yes, one would definitely advocate the use of any scraping device, particularly those which are incorporated into tooth brushes. It has been shown if you can reduce the number of bacteria at the rear of the tongue then there will be less chance of you having bad breath.

26:02 - Inside the Intestines

Inside the Intestines

with Gemma Walton, Reading University

Meera - This week, I've come to the school of Food Biosciences at the University of Reading to find out how the bugs in our body can actually help with our health. Bacteria are literally everywhere on Earth and us humans depend on them a lot. One of the ways we depend on them is to help us digest our food. A team here at Reading are using a model of our large intestine to find out just how these so-called good bacteria work. I'm here with Dr Gemma Walton, gut microbiologist at Reading University, who's going to tell me more about how these models work.

Gemma - The large intestine is the region just after the small intestine. It comprises the proximal, the distal and the transverse colon regions.

Meera - What's different between these regions?

Gemma - The small intestine is quite an acidic environment so the beginning of the large intestine is slightly acidic. It gets less acidic and more neutral as you move to the more distal regions.

Gemma - The small intestine is quite an acidic environment so the beginning of the large intestine is slightly acidic. It gets less acidic and more neutral as you move to the more distal regions.

Meera - Here, with the models I can see we've got three main bottles. I guess these are representing each part of the intestine?

Gemma - Yes, we've got out proximal, transverse and distal regions. They're held at different pHs so different acid levels by pumping in acid to each of the vessels just to maintain them.

Meera - At the front we've got a slightly larger bottle which seems to be feeding into the first stage of the large intestine and then onwards. What's in that large bottle?

Gemma - In that first large bottle would be non-digested foods that would typically arrive in the large intestine to be broken down further by the bacteria.

Meera - What bacteria are found in the large intestine then?

Gemma - There's many, many different species of bacteria in there. Typically, we have species of lactobacilla, bifida bacteria, clostridium, bacteroides, eubacteria. We used to believe the large intestine was just the area for the absorption of water but now we can see there's millions and millions of bacteria. It's actually a very metabolically active organ of the body.

Meera - How did these bacteria get there in the first place?

Gemma - It starts off at birth. When a baby is delivered vaginally the first time it is in contact with bacteria is when it leaves its mother. It's basically getting a vaginal inoculum straight away when it's born. There's lots of different species like lactobacillus in the vaginal tract. This is the first meal, if you like, that the infant will get. These bacteria that get into the infant will then use up the oxygen very rapidly. Therefore you get an area that's got no oxygen which is what we're left with. A system with lots of bacteria growing that don't use oxygen.

Meera - Once these bacteria are down there, how do they actually help our digestion?

Gemma - When you ingest a meal it goes down and it's ingested by your own enzymes and broken down in your small intestine. However, there's loads of partially digested foods actually reaching the large intestine. For example, there's some different starch molecules and the longer-chained carbohydrates that are reaching the large intestine. These can then be further broken down by the bacteria in the large intestine and broken into short chain fatty acids and other products that might be beneficial to human health.

Meera - We've got this model showing the large intestine. What are you actually trying to find out?

Gemma - In these models, this is the gross part. What we actually do is we place a faecal suspension into each vessel of the model. This is our way of putting in the bacteria that have been naturally found growing in the intestine. We're just adding them in, holding them in the different pHs according to the acid levels. We can now feed the model with different prebiotics. Prebiotics are carbohydrate-based normally. What they are, they're food for the bacteria so they're tested to see if they actually grow on them. We can feed this into our first vessel of the system and see how they affect the bacteria within there and see whether they increase beneficial bacteria and whether this can persist in the second and third vessels: whether we can actually have changes in our beneficial bacteria. We can also look at probiotics. Probiotics are actually the beneficial bacteria so we can see by having a probiotic meal what it actually does when these bacteria are mixed in the system, whether the bacteria that are ingested actually have a chance to coexist with the bacteria that are already there.

Gemma - In these models, this is the gross part. What we actually do is we place a faecal suspension into each vessel of the model. This is our way of putting in the bacteria that have been naturally found growing in the intestine. We're just adding them in, holding them in the different pHs according to the acid levels. We can now feed the model with different prebiotics. Prebiotics are carbohydrate-based normally. What they are, they're food for the bacteria so they're tested to see if they actually grow on them. We can feed this into our first vessel of the system and see how they affect the bacteria within there and see whether they increase beneficial bacteria and whether this can persist in the second and third vessels: whether we can actually have changes in our beneficial bacteria. We can also look at probiotics. Probiotics are actually the beneficial bacteria so we can see by having a probiotic meal what it actually does when these bacteria are mixed in the system, whether the bacteria that are ingested actually have a chance to coexist with the bacteria that are already there.

Meera - What have you found so far? How well has it combined?

Gemma - Different probiotics have shown some very nice results that they can work nicely with the bacteria. What we also find is that if you stop taking these the bacteria then leave the system.

Meera - So to improve your health you have to have a regular intake of them?

Gemma - Absolutely, it seems like it's the transient effect.

Meera - What result have you seen with the prebiotics, basically the things that are feeding the bacteria in your intestine. Has that been positive?

Gemma - Yes, absolutely. This is a nice way to increase the numbers of bacteria already there, the beneficial ones. We've been able to see nice increases using systems like this. In some instances we can see persistence of the prebiotic to causing increases in the more distal regions which is the area more prone to diseases.

What can you do fo bad breath?

We put this question to Marcello Riggio:Marcello: Unfortunately at the moment there is no cure or effective treatment so one should actually continue to use these scrapers where at all possible. Unfortunately there's a perception that people with bad breath have got poor oral hygiene. That is not the case. You can keep your teeth scrupulously clean and floss consistently and you will still have bad breath unfortunately. You can use zinc containing chewing gum, for example, which will help to a certain extent. There is no good solution or cure at the moment. Chris: I did hear that swilling your mouth with hydrogen peroxide in low concentrations is also quite good at killing the bacteria.Marcello: Yeah. There are a number of solutions such as hydrogen peroxide which will kill bacteria but one has to be careful that you're killing off the good bacteria as well as the bad bacteria. That's certainly something we don't want to do. These agents are non-selective.

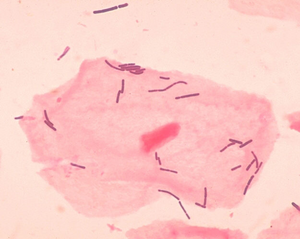

33:15 - Kitchen Science - Food Poisoning and Passing Bacterial Wind

Kitchen Science - Food Poisoning and Passing Bacterial Wind

with Simon Park, University of Surrey

Ben - For this week's Kitchen Science I've come to the university of Surrey in Guildford and I've met up with Dr Simon Park. Hi Simon.

Simon - Hello.

Ben - Simon works on Campylobacter and this is actually the most likely cause of food poisoning in the UK. But not many people know about it so Simon, how does campylobacter get into us?

Simon - It lives in the farm environment, in all the poultry flocks. So poultry flocks in the UK are actually endemically contaminated with campylobacter. When it infects chickens it's perfectly at home in that environment and the chickens are perfectly healthy so it's a commensal of chickens. During the slaughtering process the gut contents of the chicken contaminate the external meat and the carcass of the chicken. It goes into the supermarkets, we take it into our homes and it's really from that major source that we get campylobacter infection.

Ben - What does it do to us when it does get in?

Simon - When it gets in it causes a very painful diarrhoea. It's one of the most painful types of food poisoning. A lot of people that have the infection are mistakenly diagnosed as having appendicitis. It causes profuse, watery and occasionally bloody diarrhoea. In most people that have acquired the infection that clears up naturally over a two week period. Occasionally you can get relapses, stomach pain that can last up to 2 or 3 months afterwards.

Ben - Usually the stomach acid and the enzymes in our stomachs would break down the bacteria that we get on our food so how does campylobacter survive?

Simon - Unlike a lot of other organisms like salmonella and Ecoli O157, it's very sensitive in the laboratory. If you subject it to acid conditions in the laboratory it dies very quickly. What you have to remember is that the stomach can have a very low pH. It can be very acidic around pH1, pH2. It's only that acidic at certain times, when there's not a lot of food in there. When you eat the campylobacter it's quite likely that it can be protected within lumps of food and lumps of chicken and thereby survive the process of going through the stomach.

Ben - We also know that all of our digestive system is lined with its own complex spectrum of different bacteria; many of which we live with very happily that don't make us ill. How does campylobacter establish a colony amongst all this other bacteria?

Simon - It's quite a specialised organism. It has quite a different shape compared to a lot of bacteria. What you see when you look down a microscope is a very fine corkscrew-like organism that moves through liquid as if it were a corkscrew, spinning through an environment. That gives it a relatively unique ability to move through viscous environments. When it comes into the gut of a human that's consumed it what it does is it follows a path or a trace of chemicals that lead it to the wall of the gut. Whilst the lumen of the gut is packed full of bacteria the very narrow environment between the tissue of the gut and the faeces is relatively unoccupied. It swims towards that and its corkscrew shape and its drilling ability allows it to penetrate the tissue. It has a specialised niche that it occupies in the gut.

Ben - Once it's take hold of that niche, how does it actually do the damage? Does it multiply so quickly that its sheer numbers hurt us or does it release a toxin?

Simon - It certainly multiplies into huge numbers but as to how it causes illness - I started working with it about 20 years ago and we still don't know. It does produce a toxin and it also has been shown to invade gut tissue. These are two possible mechanisms. Thirdly, it maybe that because you get such high numbers of the organism there the immune over-responds to the infection and it damages the gut tissue in terms of collateral effect. The actual symptoms of diarrhoea, inflammation and pain may be generated by your immune system overreacting to the infection.

Ben - Well, it certainly sounds like something we should avoid. Is there any way we can avoid it?

Simon - It's very difficult to avoid if you eat meat and particularly if you eat chicken. It contaminates, depending on what study you read, up to 70-90% of supermarket chicken. You must be aware of that and when you handle things like raw chicken you need to use separate chopping boards and separate knives to do that. Also, be very careful when you're washing your hands. If, for example, you take a piece of chicken out of the fridge, you touch it, you start chopping it up into joints then think about washing your hands. The first thing you do is you go over to the sink, turn the taps on and you touch the taps. You then wash your hands and the next thing you do is turn the tap off. You immediately re-contaminate yourself because you touch the tap.

Simon - It's very difficult to avoid if you eat meat and particularly if you eat chicken. It contaminates, depending on what study you read, up to 70-90% of supermarket chicken. You must be aware of that and when you handle things like raw chicken you need to use separate chopping boards and separate knives to do that. Also, be very careful when you're washing your hands. If, for example, you take a piece of chicken out of the fridge, you touch it, you start chopping it up into joints then think about washing your hands. The first thing you do is you go over to the sink, turn the taps on and you touch the taps. You then wash your hands and the next thing you do is turn the tap off. You immediately re-contaminate yourself because you touch the tap.

Ben - On the subject of transmitting bacteria it's really the reason I've come to see you because for this week's Kitchen Science. We know that coughs and sneezes spread diseases and that's how respiratory infections actually get transferred. You were thinking there might be another way that bacteria could be transmitted.

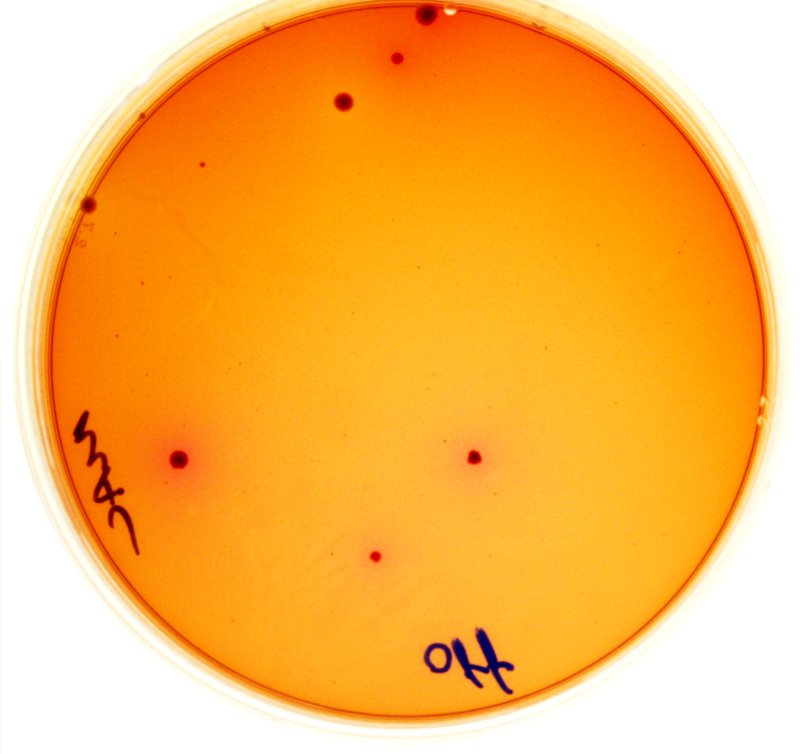

Simon - Yes, I have two sons. Joe and Josh who are aged about 5 and 7 and they've developed and obsession with this homemade biological prank: farting. I thought, why do we find this so offensive and why is it dangerous. Can I demonstrate this to my children to stop them doing it? I thought of some experiments where I could actually prove whether or not farts could transmit bacteria. What I've done is I've taken some MacConkey agar plates that are very good at culturing faecal bacteria. I've done some very crude experiments where we've exposed the plates to people farting in terms of a naked fart (no pants and no jeans on) and also people farting with underpants and jeans on.

Ben - So you've set this up by passing wind, shall we say, on what's called a MacConkey agar plate. I believe that you actually have some of these plates to actually show us:

|  |

| Plate 1 - Exposed to flatulence through underwear and jeans | Plate 2 - Exposed to flatulence without underwear and jeans |

Part 2 - now in Simon Park's Lab

Ben - One of these plates was farted on through jeans and pants. The other one was exposed to flatulence completely bare. We d like a bit of Naked Science here, of course. There are two plates. One of them clearly has some colonies on but the other one is completely clean. So, Simon, which one's which?

Simon - The plate that's totally clear is the one that was exposed with pants and jeans on. Obviously the pants and jeans are being very effective at filtering out any faecal bacteria. The plate that was exposed to the naked emission has a splattering of red colonies on it. They're very indicative of Ecoli that's a very common faecal bacteria. It's a very good indicator of faecal contamination.

Ben - So we are definitely transmitting bacteria with every flatulence.

Simon - Yes absolutely. There's such huge numbers of bacteria in a stool that it's inevitable that we would transmit bacteria after flatulence.

Ben - We've been able to catch these bacteria on an agar plate which is designed to feed them and enable them to grow. But they've been living inside us so they've been living in an environment that's quite low on oxygen, there's quite a bit of methane and hydrogen sulphide. Would these have actually survived if we hadn't encouraged them?

Simon - Yes. There's a lot of bacteria in the gut and the vast majority are strictly anaerobic so they can't grow in the presence of a normal atmosphere. They can only grow where there's no oxygen. Obviously those bacteria, whilst they might have landed on the agar plate, they wouldn't have been able to grow on the agar plate. The ones that we've isolated are probably Ecoli or coliforms that are very common in the gut. They are very robust bacteria so they will grow in air, without air and on agar plates so these are capable of surviving outside in the environment for hours if not days.

Ben - could this mean that people who choose not to wear underwear, for example Scotsmen wearing a kilt or naturists, could actually be transmitting more bacteria every time they fart?

Simon - Because there's no protection or filtering I guess that's true, yes.

Ben - So, we now know that jeans filter out some of the bacteria that might otherwise get transmitted through flatulence but could there be anything else that gets transmitted? Is there anything that might get through the jeans?

Simon - There are obviously viruses that are many orders of magnitude smaller than bacteria. Things like the norovirus which is a very common cause of vomiting and some of the astroviruses that are common in causing diarrhoea are quite likely to pass through the fine holes in things like underpants and jeans.

Ben - And did you show your sons? Have you convinced them now that farting in the house is not right?

Simon - They were quite shocked. One of the first things they asked me was 'were they friendly bacteria or bad bacteria. I had to tell them they were relatively friendly bacteria.

Ben - So obviously coughs and sneezes spread diseases, it's possible that farts do as well. Do you think we should ban farting in hospitals?

Simon - Possibly. It's very difficult to ban actually because everybody does it. Generally, on average it's about a pint glass full of gas that we emit every day. Most of us actually fart during our sleep when all of our muscles are relaxed. Even those of us that don't fart during the day: almost all those fart during the night unknowingly. It's very difficult to prevent in a hospital environment.

Ben - So it's best we just stick to normal personal hygiene - keeping our hands washed with alcohol and that sort of thing. I think the overall lesson we can take from this is it may not be best to go to a naturist's barbecue.

39:56 - Probiotics for Allergies

Probiotics for Allergies

with Gareth Morgan, University of Swansea

Chris - One of the claims about good bacteria is that they can reduce allergies and things like eczema and asthma. They can also reduce the risk of developing childhood diarrhoea but is it really true? Gareth Morgan's a researcher who's been looking at this question. He's at the university of Swansea. What is all of the thinking behind these claims?

Gareth - As you have heard earlier in the programme, probiotics are thought of as beneficial bacteria. Unlike the campylobacter that infect your intestine and make you ill these are bacteria which live in your intestine, colonise your intestine but their effects are the opposite. They give you good health. In terms of allergies there have been a number of studies looking at whether or not probiotic treatments causing these colonisations (by giving probiotics by mouth) can actually either prevent you developing an allergy or actually treat them.

Gareth - As you have heard earlier in the programme, probiotics are thought of as beneficial bacteria. Unlike the campylobacter that infect your intestine and make you ill these are bacteria which live in your intestine, colonise your intestine but their effects are the opposite. They give you good health. In terms of allergies there have been a number of studies looking at whether or not probiotic treatments causing these colonisations (by giving probiotics by mouth) can actually either prevent you developing an allergy or actually treat them.

Chris - So in other words if someone's got some kind of disturbed normal flora bacteria living in their intestine you can supplement them with what ought to be there and this can help make them healthier?

Gareth - It's not necessarily that they're disturbed. They may have perfectly normal bowel flora. By changing them or manipulating them in a direction that is beneficial those allergies can either be prevented or treated.

Chris - How do you think that you can prevent allergies just by changing the bacteria you have in your gut? For many people, myself included, the link is not obvious.

Gareth - It could well be that it's the interaction between the immune system of the intestine and then of the body as a whole with these bacteria that are living there. It's certainly the case that we know the intestine has more cells of the immune system in it than the whole of the rest of the body put together. There is continuous activity of the immune system going on in the intestine. Essentially because it's in a place where the body is exposed to the outside world. Food's coming in all the time; all sorts of bacteria; viruses; toxins are all coming into the intestine on a regular basis as we eat. That needs to be regulated and defended against. The immune system is always there: reacting, responding to the bacteria. It's the immune system that decides whether or not we respond to an allergen, something like house dust mites or pollen or another allergen in a way that gives us allergic disease.

Chris - So what experiments have you been doing to find out how you can manipulate these bacteria and how you can demonstrate these health benefits?

Gareth - What we've been doing is conducting a trial on probiotic bacteria given to mothers at the end of the pregnancy and to the newborn babies for the first six months of life. This reproduces a number of trials that have already been carried out around the world. The first one was in Finland about 10 years ago which had shown some of them, not all of them, that giving probiotics in the way that I've described can reduce the incidence of eczema in babies and young children up to the age of 2. Some of the studies have also looked at whether or not you can prevent asthma. That doesn't seem to be something that has been demonstrated yet. This is why we're doing our particular study using different bacteria, different numbers of bacteria to see whether or not we can also prevent eczema by the age of 2 years. We'll also follow these children up and see whether or not asthma is reduced as well.

Chris - Are you going to give this treatment to all children born by any route or are you tackling just children born by caesarean? In the past there have been some studies that suggest that children born by caesarean don't get this dose of probiotics off their mother as we've heard from the scientists in reading this week. This means they're more prone to getting these problems so who've you got in your study?

Chris - Are you going to give this treatment to all children born by any route or are you tackling just children born by caesarean? In the past there have been some studies that suggest that children born by caesarean don't get this dose of probiotics off their mother as we've heard from the scientists in reading this week. This means they're more prone to getting these problems so who've you got in your study?

Gareth - We've got all children in our study, so those born vaginally and by caesarean section. We've treated all infants whether or not their mothers are breastfeeding them or bottle feeding them because that's another area that's been suggested to influence allergy. Certainly, breastfed babies have different bacteria in their intestines than bottle fed babies do.

Chris - This is presumably because there are different components in breast milk that select out and encourage the growth or certain types of bacteria, which is why you see that effect.

Gareth - Sure, the bacteria themselves are there but also the prebiotics, those are the kind of chemicals that stimulate the probiotics (the beneficial bacteria) that are also in the breast milk.

Chris - How do we know that when you give these bacteria that they actually survive in the intestines? How do we know they get into people and they survive and make a difference?

Gareth - As part of the study. This is something we are particularly interested in. Many of the other studies haven't particularly looked at this. We have obtained stool samples from our babies throughout the first six months of life and afterwards to develop molecular techniques to check whether the probiotics first of all managed to establish a colonisation and then how long that lasted.

Gareth also answered these listener questions:

From Troy, Second Life:

I read somewhere that gut bacteria makes some of our vitamins for us.

Gareth - We get some of our vitamins from our diet or the body makes them themselves. That dietary source is obviously very important. Bacteria are very important in digestion and dealing with food properly. It's entirely possible that bacteria may have an important influence on how well we extract vitamins from our foods.

Chris - Does that include any specific types of vitamins?

Gareth - It could be any of them but B or K vitamins would be the type of things that would be influenced.

Did Dinosaurs Die Young?

Dr John Nudds, University of Manchester, Palaeontologist:The first thing that we can say for certain is that no dinosaur ever lived for a thousand years nor indeed for anything approaching that sort of time.

If you compare dinosaurs to present day animals we might expect that the very large herbivores, things like brachiosaurs and diplodocus which were comparable in size to an elephant would have lived, therefore, for 70-80 years. Maybe a bit more. Whereas the smaller, more meat eating dinosaurs would have been more comparable to some of today's larger birds, to which they are closely related. If you think of something like an eagle or raven they live for 20-30 years and that would probably have been the lifespan of a tyrannosaurus rex. How do we know this? Dinosaur bone is sometimes preserved in exquisite detail and we can take thin sections of the dinosaur bone and look at the bone histology as we call it - that's the microarchitecture of the bone, just as we do with modern day bone. This has shown that some dinosaur bones, especially the long limb bones and also dinosaur teeth grew in distinct layers. The teeth added new layers on a daily basis and limb bones, on the other hand, often added yearly layers. Just like counting tree rings to work out the age of a tree we can count the annual layers in a dinosaur bone to work out the age of a dinosaur.

Interestingly, some of this work has been carried out on tyrannosaurus and it's been shown that the largest known specimen: that's the one known as Sue, which is in the field museum in Chicago, would have weighed more than 5000kg when living and lived to an age of 28 years.

Do gut bacteria make vitamins?

We put this question to Gareth Morgan:

Gareth: We get some of our vitamins from our diet or the body makes them themselves. That dietary source is obviously very important. Bacteria are very important in digestion and dealing with food properly. It's entirely possible that bacteria may have an important influence on how well we extract vitamins from our foods. Chris: Does that include any specific types of vitamins?

Gareth: It could be any of them but B or K vitamins would be the type of things that would be influenced.

Are we washing off our skin bacteria using antibacterial soap?

We put this question to Marcello Riggio:

Marcello - Yeah! It's very important to have good hand hygiene but most of the bacteria on the surface of the skin are fairly harmless unless they get into the bloodstream where they can cause nasty infections. The most well-known is MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. We don't need to worry about bacteria on the skin. They don't cause any harm so long as they stay on the surface of the skin. Skin is a very good barrier and they don't get into the bloodstream.

Chris - If you strip away the good ones is there not a danger the bad ones might take over?

Marcello - There certainly is, actually but if you've got bad bacteria on the skin then as long as they don't get into the bloodstream they're not going to cause any major problems.

- Previous Did Dinos Die Young?

- Next Floating Clouds and Shining Stars

Comments

Add a comment