Building a New Heart

Interview with

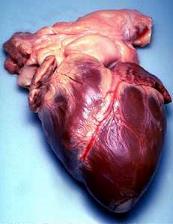

A few weeks ago, we reported on the breakthrough where scientists in America had been able to

build a beating heart in the lab. We invited Dr Steffen Kren, from the University of Minnesota, to join us on the show.

Helen - I wonder if you could first of all tell us a little bit about your beating heart and what's been going on in your laboratory.

Steffen - Sure. This is usually regarded as what's thought of as tissue engineering. The elements to create a tissue are typically cells which we can get from a variety or sources and a scaffold. In this case, we've devised a process whereby with diffusion profusion we can remove all the cells from a solid organ leaving the extra-cellular matrix, the protein that the cells excrete. This forms a remarkably detailed scaffold that represents the organ in three dimensions but it's completely a-cellular. Then using three-dimensional tissue culture techniques we can add cells back and create a new tissue that hangs on that scaffold.

Steffen - Sure. This is usually regarded as what's thought of as tissue engineering. The elements to create a tissue are typically cells which we can get from a variety or sources and a scaffold. In this case, we've devised a process whereby with diffusion profusion we can remove all the cells from a solid organ leaving the extra-cellular matrix, the protein that the cells excrete. This forms a remarkably detailed scaffold that represents the organ in three dimensions but it's completely a-cellular. Then using three-dimensional tissue culture techniques we can add cells back and create a new tissue that hangs on that scaffold.

Helen - So you basically make a mould, if you like, in the shape of the organ you want and then fill it in will cells. Is that right?

Steffen - Yes, that's right. It's even better, in a sense, than a mould because our process retains proteins that we believe guide cells to do what we need to do; that cue cells to - in the case of undifferentiated cells, perhaps - cue them to what they should turn into for that particular spot in the tissue.

Dave - Almost like an instruction manual inside the structure which you've got left which tells the stem cell, 'you should be part of a blood vessel?'

Steffen - That's right. We're hoping to (a) understand that cell signalling phenomenon and (b) use it to our advantage to create details in a tissue that we wouldn't be able to do just by providing cells alone.

Dave - So you've taken a heart. What kind of heart were you using?

Steffen - In this case, rat.

Dave - So you've taken a heart and in this case, cleaned it out of all the cells. Then you've just injected some stem cells and it suddenly grows back into a working heart?

Steffen - In this report, in Nature, we used neonatal cardiomyocytes. They're not stem cells, they're differentiated. They're young rat heart muscle cells. We sort of short-circuited the whole differential issue for this particular experiment. Are you following me?

Dave - Yes, that makes sense.

Steffen - Now the way we view this going forward in a transplant context, we would like the cells that we use to be autologous, to come from the patient.

Helen - How do you mean? Are you extracting the stem cells from the bone marrow, for example?

Steffen - Could be. Our laboratory has also found progenitor cells in adult cardiac tissue.

Helen - So actually from the heart that you're going to replace?

Steffen - This could end up a possible source. The way we see this as superior to cadaveric organ donation is that, in theory, grown from your own tissue the entire construct would be autologous save for the matrix itself. Worst case scenario the matrix is immunogenic that's rapidly turned over by smooth muscle cells. Perhaps over a relatively short course of immuno-suppression the autologous cells that we create turn over that protein matrix and it would become you in totality.

Dave - So the idea is you take someone else's heart, it doesn't have to be very good or it isn't working any more and then inject it with your own cells. Then it would grow into a heart and you could transplant that into you and it should start working. Is there any reason a human heart should be more difficult than a rat heart?

Steffen - Well, there's certainly a matter of scale and as a substitute we've used porcine tissue, cadaveric porcine hearts to be a point of principle in scaling this process to human-sized organs. Now at this point we've successfully de-cellulised a variety of porcine organs, not just the heart also kidney, liver, gall bladder - a variety of tissues. The scaling issue as far as the recent experiment is sort of beyond our mainly economic capabilities.

Dave - You need many more cells.

Steffen - Exactly. We would have to donate every square inch of tissue culture that we have to create the cells. At this point I don't really see that being a big issue.

Helen - How do you see the way forward in terms of, are we going to see the technology developed - actually used in clinical situations?

Steffen - Well, I think that even before that we're going to learn a tremendous amount of basic science about cell signalling. There may even be medical products along the way that are not entire replacement hearts. For instance, it may be that our tissue is a successful left ventricular patch in the case of an infarcted heart, for instance. So there may be steps along the way where this is useful technology, but stops short of a complete replacement heart.

- Previous Keeping Organs Alive

- Next Genetics of Prostate Cancer

Comments

Add a comment