What were you doing between 5:45pm and 6:20pm on this day three weeks ago? What clothes were you wearing? Who were you with?

Unless something out of the ordinary happened or this day is special to you, your birthday for example, your first instinct is likely to be "I don't remember." Given a little more time to think about it you might be able to say "I was probably driving home from work" or "that's usually the time I do my homework."

But exactly where you were, who was around and what you were doing may, at best, only be logical guesses. So why can't we remember these things?

Memory doesn't work like a video recorder; we don't document every little detail and we certainly can't rewind and replay our memories to see what we did. The truth is if the information isn't particularly important or out of the ordinary our brain will not put in the energy to store it.

Unfortunately, unlike a video, our memory of an event doesn't stay the same every time we recall it. Our perspectives on what happened will change depending on how we are feeling or what other information we have collected since.

Can we expect someone being questioned by the police to remember every little detail of what they did in a 35 minute period three weeks ago?

|

|---|

How do events become memories?

It is possible to think about the brain having two separate types of memory; Short Term Memory (STM) and Long Term Memory (LTM). Short term memory has many more limitations than long term memory; the capacity of STM is between 7 and 9 pieces of information and only lasts for about 30 seconds, whereas LTM is thought to have an unlimited capacity with memories that can last for the rest of our lives. But this doesn't mean that everything we experience will make it to our long term memory and things that do will not always be recalled exactly as they happened.

When we are involved in an event, cells in the brain called neurons will begin to fire rapidly in many areas. This results in a process known as memory encoding.

Encoding can be thought of as our brains receiving information and changing it into a form that it can handle, a bit like when you change money into a different currency to use in another country.

Encoding can be thought of as our brains receiving information and changing it into a form that it can handle, a bit like when you change money into a different currency to use in another country.

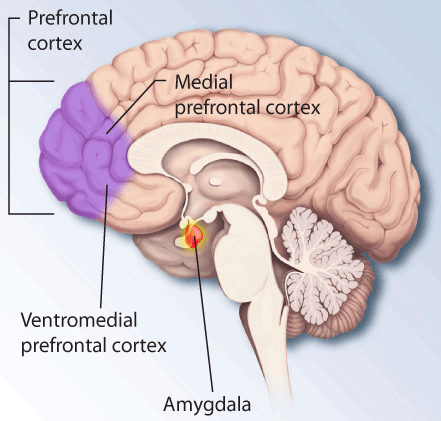

During the encoding process the brain brings together information from multiple areas; the primary sensory areas that detect visual, auditory and touch stimuli, along with the amygdala that is responsible for processing our emotions. Information from these areas comes together in the hippocampus, an area deep in the brain that organises all the incoming information and decides the best way to store the memory. The hippocampus then sends signals back to the sensory areas and these connections effectively form the memory that can later be retrieved.

Changing memories

After a memory has been created we must go through a process called retrieval in order to remember it. During memory retrieval the brain "replays" the signals it created when the memory was encoded, but unlike replaying a video, the replay of the memory will not provide an exact picture of the original event. If it wasn't different we would not be able to distinguish a memory from experiencing an actual event.

The recall of a memory is very much influenced by our current situation when remembering. Every time we remember something, new information about that memory is subconsciously incorporated. This means that the next time, (and every time thereafter) this memory is recalled it will be slightly different from the original.

Even the way we are currently feeling can change our memory of something, seeing an event through "rose tinted glasses" for example. On your last day at a job, you may look back at the experience and only really remember the good things about it if you and your colleagues are celebrating your last day.

Many simple experiments have been done to demonstrate just how easily influenced our memory is. After showing someone a video of a car crash and asking them to estimate the speed the cars were travelling, the wording of the question has a big impact on the final speed estimate. People would estimate the speed to be much higher if asked "what speed were the cars travelling when they smashed into each other?" than if the word 'hit', was used.

Adjusting and recreating a memory often doesn't really have much impact on our day to day lives. What does it matter if the man you saw coming out of the shop last week was wearing a black coat, but now that someone else said they saw him wearing a blue coat you think that's what you what saw? But it can have terrible consequences if it happens as part of a criminal investigation.

False memories

Most people can probably understand and have likely experienced their memories changing slightly over time. But is it possible for someone to have a memory of something that didn't actually happen? A memory so real that they truly believe something happened? Frighteningly, the answer seems to be yes.

Prof. Elizabeth Loftus has created a lot of attention and controversy with her ground-breaking research into false memories, particularly in relation to criminal investigations and reported repressed memories.

In a number of studies, Loftus and other researchers were able to successfully create false memories in people, including getting lost in a shopping centre as a child, having an accident at a family wedding or being the victim of a vicious animal attack. Some people are more susceptible to this than others; most studies are able to plant false memories into about 30-40% of participants. While this might not seem like a huge amount, when this is applied to a court case there is a 30-40% chance that your key witness is testifying with a false memory.

Is it possible that those people who had the false memory 'planted' actually just experienced a similar event and the memory has simply been changed? Apparently not - there has also been successful implantation of improbable or impossible memories, such as meeting Bugs Bunny at Disneyland.

Memory in a criminal investigation

Loftus has provided comment and been an expert witness in hundreds of court cases, providing information to the jury on the unreliability of memory. These include high profile cases of the Hillside stranglers and Ted Bundy. Arguably her most controversial case involved the daughter of George Franklin, who during therapy claimed to have retrieved years old memories of her father killing her best friend. Franklin was convicted of murder on the basis of his daughter's memories and spent five years in prison before his conviction was overturned.

|

|---|

Since the advent of DNA evidence many people who had been convicted of crimes have had their innocence proved. The innocence project in the United States has helped free 329 wrongly convicted people since it was established in 1992. Of these 329 cases, 75% were wrongly convicted due to eyewitness testimony. That's 246 people who spent an average of 14 years in prison, some on death row, for crimes they didn't commit.

What does all this mean for a criminal investigation? Law authorities must be careful in the way they question both suspects and witnesses. In light of the discovery of how easily human memory can be manipulated, police must now be much more cautious in their investigations. They should adhere to strict legislation that ensures interviews are conducted in such a way so as to extract all the required information, but without using leading questions that could alter the witness' memory. It has also become much more important that members of the jury are made aware of the imperfect nature of memories.

So do you remember what you were doing between 5:45pm and 6:20pm on this day three weeks ago? Would you trust that memory even if you did? Maybe try taking off those rose tinted glasses.

Comments

Add a comment