Acoustic Archaeology

Interview with

Ben - Now, as it's Christmas, there'll be plenty of carol singing either through groups knocking on your door or going to carol services in church. But why is it that some places make a choir sound good while others can make them sound flat and lifeless. Now have a listen to this.

We are joined today by Malcolm Longair who is taking Sir John's College Choir to Venice to explore the acoustics of architecture and even indulge in some acoustic archaeology. So what are we listening to right now?

taking Sir John's College Choir to Venice to explore the acoustics of architecture and even indulge in some acoustic archaeology. So what are we listening to right now?

Listen to this sample...

Malcolm - What you're listening to just now is the magnificent performance of the Jean Mouton Nesciens Mater, performed by the gentlemen of the St John's College choir, in a tiny little chapel, the Emiliani Chapel, in one of the churches we were dealing with in Venice. I should explain that this whole project came out of my wife's work. She is professor of architectural history. And since she's been working on Venice for almost 40 years, she wanted to understand exactly how music worked in the great churches in Venice.

So she was very fortunate to get a very substantial grant to study this, to characterise acoustically exactly what the buildings are like, to take the St John's Choir out to Venice to try all the possible positions and the various combinations, and also get the audience responses to what they were hearing. So my role in this was very much secondary. I was the person responsible for doing the acoustic and the scientific analysis of the data which appears as an appendix for Deborah's book which only came out just last week.

Ben - Well, I'm pleased to hear that. I think I sort of talked by your wife a little while ago. And it is fascinating stuff but what is the relationship between architecture and acoustics?

Malcolm - Exactly. That's what it was about. Now the reason that this project was so intriguing is that the Renaissance period was the time when new music was being written which required a very detailed understanding of polyphony. So the split choir is where you want to hear 8 voices or some of Gabrielli's 15 part motets. You have to have an acoustic which enable those who paid the money for the music to actually hear the 15 parts or the eight parts.

So that's a great acoustic challenge. The architects such as Palladio and Sansaviudo, they were attempting to taken into account these requirements in the churches that they were building at the same time. Now what we've been doing following the whole project went extremely well but with a bit of problem, which is when we try to simulate what they sounded like. We were getting far too long reverberation times.

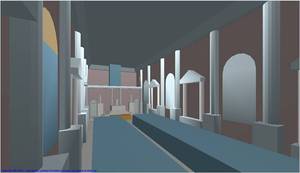

So what I've been doing with Braxton Boron, an excellent student who has joined me from the United States, we're building virtual models of all the churches from which we acquired  acoustic data. And we're trying to reproduce the acoustic volumes virtually. And the idea is that once we've done that, then we can change the nature of the buildings. We can put in different roofs. We can put in different hangings, different audiences, different clothes, everything and see how it will get to the proper understanding of what it must have sounded like in the 16th century when this is being done. So it's an absolutely wonderfully, great-fun project.

acoustic data. And we're trying to reproduce the acoustic volumes virtually. And the idea is that once we've done that, then we can change the nature of the buildings. We can put in different roofs. We can put in different hangings, different audiences, different clothes, everything and see how it will get to the proper understanding of what it must have sounded like in the 16th century when this is being done. So it's an absolutely wonderfully, great-fun project.

Ben - You've brought some samples with you today actually. Now this first one, this is the real acoustics. This is what it generally sounds like...

Listen to this sample...

Ben - Where is this?

Malcolm - Yes. This is the most wonderful place in Venice which if you go to Venice, you can go into the Ospedalettoo. It's got the most wonderful acoustics. This is the sopranos from the Sir John's Choir singing from the organ gallery of the Ospedalettoo and being recorded in the middle of the day. It's quite a small volume but a very simple shoebox-like shape.

Ben - So it certainly sounds lovely. But how do you go about analysing the actual acoustics in there? How do you find out why it sounds so good?

Malcolm - Well, this is great fun. What we did was to characterise acoustically using the most modern equipment, sourced different microphone positions. And we did many positions within each of the churches so that we've got all the acoustic parameters that we need, the wave forms coming from all of these.

Once we've got that, then Braxton has built a virtual model of the church. And then we run it through the most recent program, which is a program called Odeon, developed in Denmark, which enables you then once you put all the materials on the wall was marble, lathe and plaster and so forth to get what the response looks like.

And so once we've got that, we can check that we got this now the calibrated data for this existing church. And we can then try to get this sound all the acoustic characters. Now that we've done that just for the last two weeks. Once we've done that, then we can put an anechoic recording of the choir through our virtual church and see if we've got back to where we are.

Ben - So we have an accurate recording of the choir here. Now this is in the room that just keeps down all echoes in it.

Malcolm - This is done in West Road in the Music and Science Centre that Ian cross runs there. And we've got the choir in it. They hated this. This was really terrible. They did not enjoy this experience at all. But you will hear what an anechoic signal sounds like...

Listen to this sample...

Ben - Oh they certainly sound very capable. But it does sound very flat.

Malcolm - It sounds very, very dry. Right?

Ben - Yes.

Malcolm - So what we now do, we take that same signal. And we put it through our  virtual model of the Ospedalettoo. And you can see what it sounds like...

virtual model of the Ospedalettoo. And you can see what it sounds like...

Listen to this sample...

Ben - So all that beautiful reverb are really bringing certain music to life. It's all fake. It's all simulated.

Malcolm - Well, Ben, it depends on what is real, what is simulated? Let me explain why we're doing this. The reason for doing this is this is the simplest example that we could get. And we wanted to find out the rules we have to follow to be able to do accurate reconstructions of the huge churches in Venice, things like San Marco, the Redentore, the San Giorgio Maggiore, which we will now begin to do.

But there we know that the huge volumes were very, very bad for acoustics. We've got 68 second reverberation time. So how did the people actually hear the wonderful polyphony that was being written by the Gabriellis, Bach, Monteverdi, and people like that? Well what we believe is that by the time you put in all the decoration, the hangings, the large audiences, we will be able to bring down the reverberation time so that everybody could appreciate the genius of the polyphony.

Ben - Well, that's fantastic. I'm afraid we're going to have to leave it there. But that's Professor Malcolm Longair explaining how we can use acoustic modelling to recreate the sound of churches that have long since disappeared or changed their roofs or changed their dressings and find out really what the experience would have been like.

Comments

Add a comment