Biology in a brewery

Interview with

Microbial contamination is a big problem in some situations but is also essential in others, like beer making. So, what is the secret of afine ale and how do brewery practices influence the movement of microbes around a plant? Nicholas Bokulich has been using DNA techniques to find out.

others, like beer making. So, what is the secret of afine ale and how do brewery practices influence the movement of microbes around a plant? Nicholas Bokulich has been using DNA techniques to find out.

Nicholas - What we were looking at here was how microbes move around food production environments. Breweries are a great place to explore this because microbes are essential to beer production, but they're also involved in spoilage of beers. So, we thought this would be the perfect place to really pattern the microbes as they move around throughout the air.

Chris - And you can follow that, can you?

Nicholas - We can. We go around the brewery at different times of year and we take a little swab. It's just like a, you know, a Q-tip for your ear. Rub it against different surfaces, different pieces of equipment, we collect different samples of ingredients, samples of beer. We take this all back to the lab, extract its DNA, and then sequencing instruments help us look at every individual piece of DNA. Which is kind of like, you know, crime scene investigation but of microbes. You can identify exactly what organisms are there.

Chris - And when you do this, what do you learn? How does this change our understanding of what's going on in these sour beer, these coolship ale processes, that gives them their unique characteristics?

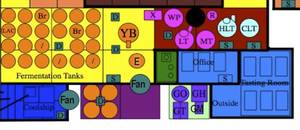

Nicholas - We're looking at which microbes are in fermentation, which microbes are in the fermentation environment, at different times throughout the year. We can track their movements throughout the year and we can understand how they move from place to place, how they're introduced to the product and make it into the fermentation.

Chris - Tell us more about, actually, what you saw when you did these experiments.

Nicholas - Looking in this brewery, the microbes have favorite hangouts. For example, some microbes, certain yeasts, and certain bacteria would be present on the floors of the brewery. Others kind of hung out around the barrels, others around the grain, and they kind of stuck to these areas season to season. So, we could see that there were certain microbes associated with certain areas of the brewery and ingredients in the brewery. Some liked it before fermentation, some liked it areas where actively fermenting beer was, and some liked it with finished beer was kind of sitting around.

Chris - What's, kind of, new here? I know you can actually put some identities on some of these microorganisms, but if you'd asked a microbiologist to speculate wouldn't they have predicted exactly what you saw happening anyway?

Nicholas - That's true. As far as the microbial identities go, the most exciting part I think is actually looking at the hop-resistance genes. I think that's probably the newest and most interesting, exciting part of this paper.

Chris - Tell us a bit about that.

Nicholas - These are genes that have, specifically lactic acid bacteria, contained within them that help them resist these antimicrobial compounds that come from the hops. These are compounds present in the hops naturally and when the hops are boiled, it releases and changes these compounds to increase their antimicrobial potency. And so, this is one of the reasons why hops have actually been used in beers traditionally for the past several centuries, because traditional brewers recognized that if you put hops in beers it made them less susceptible to contamination from negative microbes. But lactic acid bacteria living in the brewery environments for such a long time have actually evolved and adapted to meet this challenge and developed these components that actually protect them against these antimicrobial compounds. Help them pump them out of the cells so that they don't kill the cells. However, no one has actually looked at these within a brewery environment like this to understand how common and how abundant they are. And so by looking at this, we were able to see beer contact promotes the growth of these microbes and retention of these hop resistance genes on different pieces of equipment.

Chris - Are we seeing a problem in the future for brewers? I would use the, well I'm going to use the horrible phrase, are we sort of brewing up trouble for ourselves in the sense that as these things become more common, because they're being strongly selected over time to become hop-resistant, are we going to have to start adding antibiotics into our beer in order to suppress these unwelcome invaders?

Nicholas - So, that's a good question. I think the answer is really, no. Beer contamination has been happening for centuries. This is a natural product. Hops are a natural product and they contain a number of different antibacterial compounds. And so while bacteria that contain these hop-resistant genes are usually very adept at resisting these hop antimicrobial compounds, they're not completely immune. Larger doses of hops can wipe them out.

Comments

Add a comment