The BRAIN Initiative

Interview with

Meet the man responsible for putting neuroscience on the American political agenda.  We find out how 500 million dollars will be spent over the next decade. Ask why more has not been invested? And find out what the Initiative hopes to achieve...

We find out how 500 million dollars will be spent over the next decade. Ask why more has not been invested? And find out what the Initiative hopes to achieve...

Hannah - Hello. I'm Hannah Critchlow reporting from Washington DC for this special Neuroscience podcast in partnership with the International Neuro Ethics Society. We'll be taking a journey into the future to explore how brain findings may shape our future society.

Last year, both the US and European Union announced investments of over 1 billion pounds in research attempting to understand how our brains work. A similar level of funding was injected over a decade ago for the sequencing of the human genome. With new information, comes ethical issues on how to use it. In the case of human genome companies filed patents for the intellectual property of our genes. Insurance companies proposed premium prices for those carrying genes predisposing to disease, and governments are using our data for their research.

As this decade kick-starts the era of the brain, cash injections will bring a revolution in neuro technology that will allow us to peer into the human as never before and to understand, and manipulate our behaviour. Who will own that data and how should we use the information?

In Washington DC, just around the corner from the White House, the International Neuro Ethics Society hosted their 2014 meeting to discuss these issues and more. In this special Naked Neuroscience series supported by the Wellcome Trust, I'm reporting from the meeting to explore how brain findings may shape our future society. In this episode, we meet the congressman responsible for setting neuroscience on the top of the American political agenda.

Chaka - On the brain side, we're almost nowhere. Unlike other medical research, only 1 percent of what will work in an animal circumstance will work in a human being when we come deal with brain illnesses. So the research the research doesn't translate well. In other areas, about 50 percent of the research, animal to human translates. Where people see success, they're willing to invest more and that's part of the challenges. We have to be prepared to invest and fail in order to be able to invest and succeed.

Hannah - Ask the man heading the European human brain project. Is this brain mission akin to a space race competition or will countries work collaboratively?

Henry - There's no time for competition in the brain. There is time for collaboration. Collaboration is essential. The problem is too vast, too complex. It's too diverse that we cannot afford to approach the brain in isolation in a silo.

Hannah - And we discuss the ethics of using these new neuro technologies, including the example of a man who used the new treatment for depression of electric brain stimulation and developed and unintended side-effect and was constantly electrifying his brain.

Stephen - The device becomes an addictive stimulation to the brain. So cocaine, narcotics, they are addictive because the affect certain brain structures and so one issue with brain stimulation is that there may actually be effects that were unanticipated. And so, a contract between the patient and the physician I think is very important.

Hannah - All to come... I first met Congressman Chaka Fattah who was responsible for initiating this investment in brain research in the States.

Chaka - I think it's critically important that we seize the moment to grapple with some of the 600 plus diseases and disorders of the brain. We have over 50 million Americans suffering from everything, from Alzheimer's to epilepsy, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, you go through the laundry list. We need to make more progress to improve the life chances of these Americans, and that's the impulse for my work. We want to make a difference, and I believe that we will.

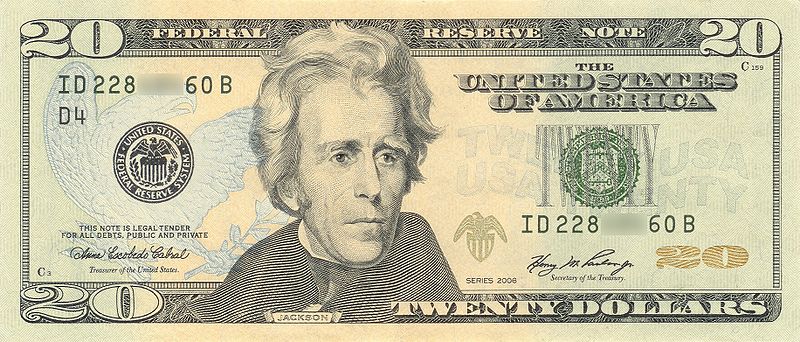

Hannah - America has raised over 200 million Great British pounds or the equivalent of that in dollars for the brain initiative. Who is investing in this, and what will the money be spent on? What's the ultimate goal?

Chaka - Well we have a multi-faceted effort, right? So we have the brain initiative which is about mapping the brain but in truth, it is about developing tools, developing the technology to help us understand how the brain actually functions. We today can't even tell you the actual number of cells in the brain. We have very little idea about the inter-connectedness in the sections of the brain, and we have a lot of work to do. This new effort about mapping the brain... this is the first time we're taking on the initiative of really trying to understand the brain, how a healthy brain should function.

Hannah - And you describe the brain as one of the final frontiers in scientific research and so you're going to be helping to invest in technologies that will allow us to peer between the space between our ears. So, the human genome project is a really good example of big investments, so 1.5 billion British pounds were invested in this in order to sequence the human genome. And this was completed, or the first draft, was completed over a decade ago. How has that translated into treatments for humans? How has that helped society?

Chaka - It's extraordinary. The human genome is a good example in which government investment, it took almost 3 billion dollars to be able to do it, right? But now we're at a point where for about a thousand dollars, you can have your own genes analyzed and know what may be some of the ways to go about dealing with disease in your own body and it revolutionized medicine. One of the interesting things about human genome is that started in our Department of Energy. It didn't start in the National Institute of Health. They said, "Oh! That's not a great idea."

Hannah - And so, the brain initiative really is a true collaboration between the Federal Drugs Agency, for example, and DARPA who are involved in defence and military, and also IARPA which is involved in intelligence, a number of other national bodies that are investing in this brain initiative to help us to understand the brain a bit more. But it is only 200 million Great British pounds. Do you think we need something more along the lines of the human genome project which, as you said, cost about 1.5 billion British pounds or 3 billion dollars. Do we need more investments in order to make headway as it were in this brain initiative?

Chaka - I think we do but we should understand that this is an annual appropriation and that when we look at the costing out of what we're doing, NIH says it's going to be about 4 billion dollars over the next, you know, 11 years. So it is a relatively expensive proposition.

Hannah - Breast cancer alone has had investments of the equivalent of 400 million Great British pounds in the last year by America. And yet this only affects 1 in every 16 people so there seems to be a disparity between the amount of funding that's available for cancer or breast cancer, for example and mental health or brain conditions which affect 1 in 4 people worldwide. So why is there that disparity?

Chaka - We need to be investing more overall in medical and scientific research, period. So it's not a matter of doing less, we should be doing more and a lot of these categories. The difference in cancer is we've had so much success. We've beaten cancers completely. We have 800 different treatment and pharmaceutical approaches that deal with cancer. On the brain side, we're almost nowhere unlike other medical research only 1 percent of what will work in an animal circumstance, will work in a human being when come deal with brain illnesses. So the research doesn't translate well. In other areas, about 50 percent of the research, animal to human translates. Where people see success, they're willing to invest more and that's part of the challenge, is that we have to be prepared to invest and fail in order to be able to invest and succeed.

Hannah - And I suppose generating the basic technologies that will allow us to understand how those hundred billion brain cells are connected with those hundred trillion of connection. So you're funding in how a brain works in the first place and how we can look at it which would hopefully generate more funding for new treatments.

Chaka - We've been studying of flies for decades and we can't tell you exactly how they work or a mouse brain. We have a lot of work to do. The brain is, I think, extraordinarily complex piece of machinery. The former President of Israel said that we have these human brains that has allowed us to build super computers but hasn't given us enough information yet to understand how our own brain works. And we have to kind of turn inwardly and focus on this if we're gonna solve some of these challenges.

Hannah - So in terms of the human genome project some companies have filed patents for intellectual property for the genetic information that's come out of it. Do you think the same thing might happen with information about our brains and behaviour?

Chaka - Well, litigation is part of a civilized society in which people will have different points of view, end up in courts of law, they try to settle them. So it could happen but it shouldn't in any way dampen our enthusiasm and I think at the end of the day, what we need to be doing from government finance resource research is to make sure that it's open and available to everyone. No one has any intellectual property control over it.

Hannah - Congressman Chaka Fattah.

- Previous The Human Brain Project

- Next The mental scars of cancer

Comments

Add a comment