Developing the HPV Vaccine

Interview with

Virologist Margaret Stanley explained her work developing the HPV vaccine, aimed at lowering  the rates of cervical cancers to Chris Smith and an audience at the Cambridge Science Centre..

the rates of cervical cancers to Chris Smith and an audience at the Cambridge Science Centre..

Margaret - Well, I work on viruses called papillomaviruses. They're incredibly interesting because they only live in the epithelium that covers your body like the skin and the interior of your mouth and the interior of the reproductive tract, and your back passage. Most of the time, these viruses do no harm. In fact, if you ever see - an effective one it's likely to be a wart. But they're a huge family and like all families, they have black sheep.

The black sheep of this big family cause cancer. The cancers they cause, the big one is cancer of the cervix in women. Now, that is a huge problem in the world. It's the second commonest cancer in women worldwide. In Sub-Saharan Africa, it's the commonest cancer in women. So, we're talking about a really serious disease. Now, it's not just the cervix. In men and women, it causes cancer of the anus which is the back passage. It causes cancer of the tonsil and it also causes cancer in women in the vagina and vulva. So, we're talking about something really important. In fact, 5% of all cancers are caused by these viruses to one in particular...

Chris - How does it cause cancer in those places?

Margaret - Well, that's a very interesting question. First of all, the virus doesn't intend to cause cancer. Cancer for a virus is a dead end because viruses exist to make more viruses and that means they have to reproduce. Now, when viruses cause cancer, they are no longer able to reproduce in the cell, so it's a bad news for the virus.

It's because these viruses, particularly this 116, carries two genes which are really important for the virus to reproduce. But if those genes are expressed in the wrong place in the epithelium because epithelium we're talking about looks like a brick wall. Normally, these two genes in the virus are made in the upper parts of the bricks. But in the cancers, they're made right in the bottom and that's absolutely the wrong place because that's where the cells are dividing. These genes distort the way cells divide and that's...

Chris - So, the virus puts those genes into the cells and makes the cells grow more than they should.

Margaret - Grow more than they should and not only that. It stops them distributing their DNA and their chromosomes properly. So, they end up with abnormal numbers of chromosomes and they end up able to accumulate more and more errors. That's how cancers develop.

Chris - So, how did you turn the virus into a vaccine that could prevent those diseases? How did you do that?

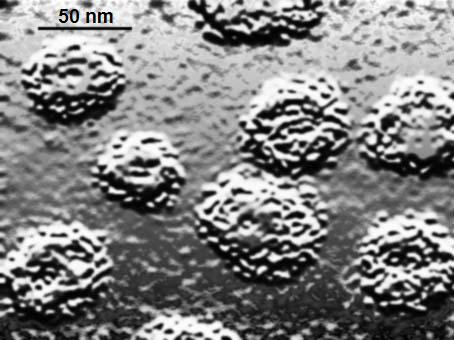

Margaret - Well, what you have to do is prevent infection with the virus. We can't act on the cancer, but what you can do is prevent women and men being infected by this virus by giving them a strong immune response. And so, what you do, this is what's been so interesting is we make shells of the virus particle. A virus looks like an egg. It's got a shell and what you do when you make the vaccine is, you make the shell, but you don't have the interior, you don't have the DNA. This shell, to the body's immune system, is exactly like the real virus and it makes antibodies to the proteins in the virus shell.

The big technical advance was being able to make these shells we call them virus-like particles. They're incredibly effective. They generate really strong defence responses and we know that these vaccines work. We know they work because the vaccines are now being laid out in certainly the industrialised world. In Australia in particular where they've been vaccinating since 2007, we can already see the decline in infection with the virus and we can see the decline in the pre-cancers caused by these viruses. So, it's a triumph.

Chris - Let's take some questions. First one over here...

Julian - My name is Julian.

Chris - Hello, Julian.

Julian - You were talking about vaccination and we have a policy in this country to offer vaccination to teenage girls for human papillomavirus. Do you think we should extend that to teenage boys as well?

Margaret - Yes. You're talking to the converted. The policy of giving it to girls was developed because at the time when all these policies were being generated, focusing on cervical cancer was the focus. But now, in the time that's elapsed, we've got a lot more information. So, we know how much male cancer there is. Basically, if you leave 50% of your population unprotected, then you've always got a great big pool of susceptibles. So, it's a much more sensible policy to immunize everybody. Then you don't have to worry how long the protection's going to last because everybody's protected.

Chris - Yes, madam.

Joti - My name is Joti and I'm from Cambridgeshire. Is there any selective population who is more susceptible to the viruses?

Margaret - No, that's another thing. If you went out and took a million women, we know that probably 800,000 of them would get infected, just because that's the way that virus transmits. But we don't know why some people are susceptible and can't get rid of it. It's not to do with ethnicity. It's not to do with behaviour. ..

Jodi - Haplotype?

Margaret - Haplotype, no. We do not have a handle on what the immunogenetics are, what is it about an individual and their ability to defend themselves against this virus.

Chris - Why is it Margaret that you catch it, but then you don't get the cancer for years?

Margaret - Because you get rid of it. Most of it, you get rid of. But also, you're looking in those people who develop the cancers, you're looking at chance events. You're looking at the probability of a molecular accident. Now, you can do the statistics - how often do mutations occur? So these are chance events and that's why it takes time.

Chris - Yes, sir.

Alex - Hi. My name is Alex. I'm from Cambridge. I have two very quick questions for you. The first is, you said we're all exposed to these viruses and yet, we need a vaccine to make an immune response so why is that? And secondly, you also said that we couldn't make a vaccine against the cancer. Why can't we make a vaccine against the cancer since the cancer would also have these viral particles in it?

Margaret - First question, I forgot it.

Chris - If we can make an immune response to the vaccine, why can't you just use your own immune response to boot virus out?

Margaret - Okay. This is a virus that only lives in the skin. Because of that, it is not very well exposed to the immune system. Now, you have to get into the circulation to the lymph nodes to generate a good immune response. And so, actually, in natural infections, you don't make a good immune response to this virus. Even though it's a pretty lousy immune response, still most people actually manage to get rid of it. The real issue for whether you're going to get cancer or not is whether you're one of those individuals who cannot clear this virus, cannot get their immune system to really deal with it. And I don't know who these people are, which is why you immunise everybody to give them a strong immune response because when you are immunised, you put your vaccine into the muscle. So, you go way beyond the skin and that way, you get straight into the lymph nodes to where the body really generates its defences.

Chris - Just very briefly Margaret, the second question which is, we can vaccinate against the virus. Why can't we just vaccinate against the cancer?

Margaret - Because cancers as they develop have evasion strategies which evade the immune response, which deregulate the immune response. So, it's a bit like turning a huge tanker around, trying to generate an immune response against the cancer that's going to be effective because that cancer has spent 15, 20 years, avoiding the immune response in the host.

Chris - It's become quite well practised We've got time probably just for one more question, young lady just down here.

Grace - Hi. My name is Grace and I just wondered why some people get cancer and others don't.

Margaret - If I knew that question, I'd be on the plane to Stockholm for the Nobel Prize. Some people are susceptible to these virus infections. Cancer is not one disease. It's a word that describes many diseases which occur in particular sites. So, I'm talking about cancer in the cervix and I know what causes that cancer which is a virus. But if I was talking about cancer in the breast, I don't know what causes cancer in the breast. I don't know why some women get it and others don't. Each cancer has its own profile, has its own risks, and these are different to a cancer in a different site. So, I can't answer your question properly.

Comments

Add a comment