Draining the Fens

Interview with

Cambridge was once surrounded by a marshland called the Fens. But in mediaeval times, and with the advice of Dutch drainage experts, the area was dried. The water now exits to the sea via an intricate system of ditches and rivers that empty into an engineering marvel called  Denver Sluice. Graihagh Jackson went to see how it was done all those years ago...

Denver Sluice. Graihagh Jackson went to see how it was done all those years ago...

Graihagh - Through much of this year so far, Britain has been facing a flood crisis. Some parts of the country have seen more than half a metre of rain this winter, 36% more than normal. As a result, thousands of homes have been flooded. But flooding and flood management isn't just a recent phenomenon. In fact, the UK has a long history of water management with one of its bravest endeavours being the reclaiming of The Fens. In 1631, they drafted in Dutch engineer, Cornelius Vermuyden and the draining began. Today, the canals are sandwiched with grassy embankments protecting the lowlands and its cows from flooding. But I was keen to know what the area would've been like before all this engineering began. Keith Hinde is a local historian and he painted me a picture.

Keith - In the summer, it was what you would call grazing land, but in a bad winter, it would've been very much like the Somerset levels are now, covered with water.

Graihagh - So, what exactly did they do to drain the fens in the early 1600s then?

Keith - They had this man called the Vermuyden, a Dutchman. His main thing in the south level was to construct two major channels, or rivers, through the middle of the fen and in between he created a wash-land so that when you got flooding, they simply filled the wash-land. Then at the end of the 2 rivers which were 20 miles long, he installed Denver Sluice to control the water flowing out to the sea, at King's Lynn. In that way, he mostly preserved the rest of the fen from flooding.

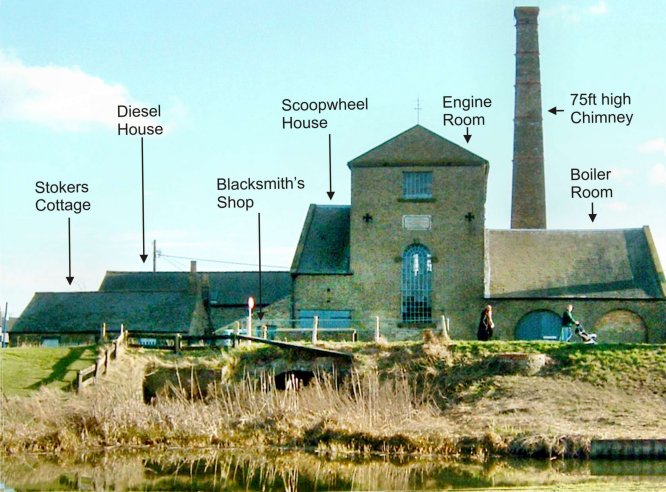

Graihagh - But as the pit shrank and the level of the land fell, it ended up lying lower than the rivers, so the water had to be pumped up and into the river, initially using wind-powered pumps. Then with the advent of the industry revolution, steam. The heat generated from coal was used to create steam at high enough pressures to power a water wheel which could remove 120 tons of water every minute. Sadly, most of these steamers have since been decommissioned. There is however, one complete relic left, Stretham Old Engine. Built in 1831, the yellow bricked building and its 75 foot chimney sit a few feet away from the canal. Inside is a beam engine complete with 3 huge boilers. Malcolm Hensby is a Trustee here and he took me for a tour.

Malcolm - So, James Watt invented the beam which is at the top of the engine and it turns the vertical power created by the piston going up and down to a circular motion which turns a fly wheel, which turns the scoop wheel which lifts the water from the low lying land to the river. Although it last worked under steam in 1941, we have more recently installed an electric motor which turns the machinery at a very slow speed.

Graihagh - So, how big an area exactly would've this place have been draining?

Malcolm - About 6,000 acres.

Graihagh - What sort of operation would that have been?

Malcolm - There was a permanent staff of two and I think the longest period it worked was 6 weeks continuously. During that time, the engine would use about 5 tons of coal per 24-hour operation.

Graihagh - So, what happens today then?

Malcolm - It's redundant and has been since 1947 when the engine was taken out of commission and replaced by the system today which is a series of remotely controlled electric pumps, all controlled from Denver and that controls the level of the water in the river system throughout the entire region.

Graihagh - The Denver Complex is one of the largest sluice systems in the UK. These 5 concrete barriers hold back the tides from drowning much of Cambridgeshire and Suffolk, as well as quickly discharging waters out to sea in periods of heavy rain. The head sluice is made up of 4 concrete segments, the big eye, a navigation gate for large vessels and the little eyes which are three smaller, but by no means small sluices.

Dan - Dan Pollard. I'm the Superintendent for the environment agency at the Denver Complex.

Graihagh - How exactly does the Denver Sluice System operate?

Dan - It works by drawing floodwaters down from Ely and Cambridge. And so, we have to change the gradient on the levels here so it draws down huge quantities. We've got the head sluice that we're standing next to, can put up to 120 tons of water a second.

Graihagh - Why do you need a sluice?

Dan - So during the summer months, we use the sluice to actually control water to make sure there's enough water in there for the boats. So the sluice is one, for getting rid of floodwater, but two, for actually maintaining river levels, and the low flow conditions too.

Graihagh - There's also been a bit of press about dredging. Should we be doing more of it?

Dan - We have had a report done not so many years ago called the tidal river strategy. It did say that dredging in this area is not sustainable purely because of the cost.

Graihagh - How might our rivers be managed in the future then?

Dan - I think there's got to be - it's got to be one situation dictates. Each case has got to be looked at individually whether we pour more concrete and more stone into an area or whether we have some sort of soft-defence and some sort of strategic retreat.

Comments

Add a comment