Placentas teeming with bugs

Interview with

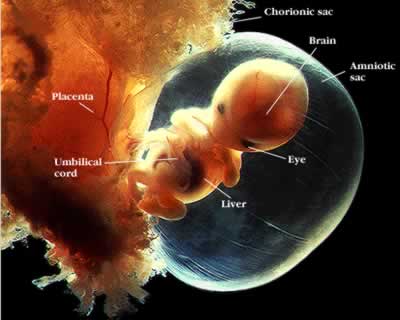

Hannah - Now, sticking with the subject of bugs, we don't want to put you off the  football on your tea, but our bodies are teaming with trillions of bacteria anytime. In fact, 9 out of 10 cells in your body are bugs. As I called 'microbiome', it's usually made up of friendly bacteria that live in the gut on the skin in the mouth and elsewhere, helping to keep us healthy. Billions of bugs are already on us and inside a baby within the first few days of life. But where do these bugs come from? Kjersti Aagaard from the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas thinks that she's found the answer and it's not what you might expect. Kat Arney spoke to her to find out more.

football on your tea, but our bodies are teaming with trillions of bacteria anytime. In fact, 9 out of 10 cells in your body are bugs. As I called 'microbiome', it's usually made up of friendly bacteria that live in the gut on the skin in the mouth and elsewhere, helping to keep us healthy. Billions of bugs are already on us and inside a baby within the first few days of life. But where do these bugs come from? Kjersti Aagaard from the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas thinks that she's found the answer and it's not what you might expect. Kat Arney spoke to her to find out more.

Kjersti - The question we're trying to answer is, does it start at the time of birth, does it start depending upon how that baby is born, whether it's through the vaginal canal or via caesarean?

And we had a couple of clues early on that it may actually precede the immediate time around birth. So, other investigators, if they looked at the phyla, the different bacteria in an infant's gut in the first week of life, at a very high level view, they found out that half of the bacteria that are present were what we call actinobacteria which includes bifidobacterium and propionibacterium. And then there were smaller minority that were bacteroidetes and firmicutes. Included in this firmicutes is lactobacillus. What we were intrigued by is that very small 10% to 20% or so that are present in that infant in that first week of life, lactobacillus, were really the only ones that are dominant in the vaginal flora. In other words, some 80% or more of the different types of bacteria that populate that infant at the time of birth or within that first week of life weren't coming from the vagina.

Kat - Now, that's very controversial because we sort of have this idea that as baby comes out of mum, it gets covered with all these bacteria and that's what colonises it. Where have these bugs come from?

Kjersti - We said there were kind of two things that weren't making a lot of sense to us. So, one was what I'd call the science math which was, what was present in that infant's gut didn't seem to match real well what was present in the vagina. In addition as a clinical obstetrician, babies don't spend a lot of time hanging out in the vagina on their way out of the uterus and into the world. They're moving through it pretty quickly. So, how is it exactly that they would acquire all of these microbes, simply as the passage through the birth canal? So, we were curious whether it was possible that first of all, the infant wasn't that sterile at birth and whether or not it was actually being exposed even in normal non-infective settings prior to delivery.

Kat - Where are these mystery microbes coming from?

Kjersti - Now, when we were just starting to complete this study, another group here in the US showed using very traditional microscopic techniques that if you looked in the placenta, nearly a half, just over a third or so, had evidence of bacteria in completely normal, uncomplicated, non-infected placentas. So, we kind of took that up and said, "Great! We're going to use a metagenomic or DNA based microscope. We're going to look as detailed and as robustly as we possibly can within that placenta and see what actually is there and what they're capable of doing."

Kat - And so, what did you find?

Kjersti - So, what we found was that first of all, there were bacteria present in the placenta. Now, they're what we call low biomass which means that the placenta isn't teaming with that bacteria. If we had to make a rough calculation, we'd say that for every pound or approximately 500 to 600 grams of placental tissue, there is about a gram of bacterial DNA. We don't really know what that equates to per number of cells because we haven't figured that out yet, but that work is underway and we may get a better appreciation for it. But when we looked at who was there, what we found when we compared it to other microbiome body sites is that placental microbiome started to look the most like the oral microbiome and didn't actually look very much like either the gut or the vagina. It really looked like the mouth.

Kat - Now, this is just getting weirder. So, how does the kind of bacteria that are in the mouth get into the placenta and then how do they get from the placenta into the baby?

Kjersti - We don't know exactly how they get there. We can make some educated guesses as to how we think they get there and we think they're primarily spread through the blood. What we think is that some of the bacteria that are in the mouth actually do a very good job of making their way through the endothelial linings in blood vessels, and potentially then pave the way for other bacteria like E. coli to make their way.

Hannah - That was Kjersti Aagaard from the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas. So Ginny, bearing that in mind that there's this amazing biome in the placenta, if you gave birth, would you eat your raw placenta or maybe offer it to your boyfriend as a present? I don't know.

Ginny - I must say that's something I've never actually considered before. It's a bit gross. I'm first kind of thinking but I guess if there was some strong scientific evidence that it would provide a benefit then I might consider it. But I think I'm going to wait until there'll be a few more studies before I say yes for sure.

- Previous Pricing the value of life

- Next Dengue World Cup

Comments

Add a comment