Test for every virus that infected you

Interview with

US researchers have developed a new test which detects every virus infection you have ever contracted, using just a drop of blood! Humans can succumb to tens or even hundreds of viral infections over a lifetime. And although the majority are cleared by the immune system, certain combinations of infections earlier in life might alter your chances of developing other diseases later, like asthma, diabetes or cancer. So the ability to screen for every virus infection you've ever had could make a massive impact on our ability to diagnose, treat and predict disease. Chris Smith spoke to Stephen Elledge...

succumb to tens or even hundreds of viral infections over a lifetime. And although the majority are cleared by the immune system, certain combinations of infections earlier in life might alter your chances of developing other diseases later, like asthma, diabetes or cancer. So the ability to screen for every virus infection you've ever had could make a massive impact on our ability to diagnose, treat and predict disease. Chris Smith spoke to Stephen Elledge...

Stephen - People are infected with viruses all the time. Your immune system is what keeps you healthy and keeps the virus from killing you. Every time you get infected with the virus, it leaves an indelible mark on your immune system, a memory. We were interested in trying to measure this memory. The way that we were doing it is that your body makes antibodies to viruses. We wanted to take antibodies out of people's blood and develop a method that will allow us to determine which viruses those antibodies recognise. That will tell us what viruses you've been infected with throughout your life. Not only did we want to be able to do that but we wanted to do it for all viruses at one time. So, we could look at over a thousand human viruses in one experiment and tell you which ones you've been infected with because your body continues to make antibodies to a virus even after the virus is gone.

Chris - How do you assemble such a massive repertoire of tests to pick up all of those different antibodies that say, I will have made and assembled during my 40 years so far of interacting with the microbial world?

Stephen - Recently, it's become possible to make various pieces of viral DNA that encode the proteins the virus needs to grow in people. It's these proteins that your antibodies detect. Since we were able to take the DNA from the sequences of all known viruses, we could make bits of each protein for each virus. And we could display that in a way that we could figure out which bits your antibodies recognise.

Chris - How do you tell which antibodies are reacting with which bit of which virus?

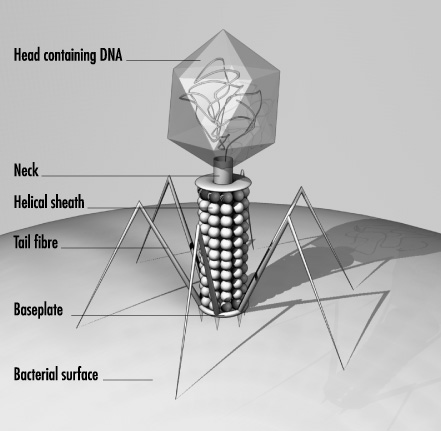

Stephen - We take advantage of something called a bacteriophage, which is a virus for bacteria. We can insert any piece of DNA we want into those viruses. So, we could, for example, insert a tiny bit of human virus DNA into the bacteriophage. The bacteriophage builds a little house that encapsulates its own DNA. The proteins on the outside of the house, we can have our little bit of viral protein fused to it. So, it decorates the house. Then, an antibody can recognise that and we have special magnetic beads that will then purify the antibodies away and if they happen to have touched a particular house, it will bring with it its own DNA and then we can just sequence the DNA. That all sounds very complicated but in fact, it's really simple.

Chris - I get it. So, because these individual little bacteriophages - these viruses that prey on bacteria - because you're decorating each of those to have a specific marker corresponding to an antibody which I have made when I responded to a certain virus in the past, any time those antibodies bind to one of those bacteriophages, and because the genetic message in the bacteriophage is unique to that particular one, you can easily pull it out and say, "we know which antibody it was that bound onto you, and we can therefore work out which antibody Chris has got in his bloodstream."

Stephen - That's exactly correct and you said it much better than even I can!

Chris - I was lucky, wasn't I? So, what are the implications of this then Steven? It's all very well to say, well, you can make these incredible deductions about what has happened to me as I've gone through life and interacted with what must amount to thousands of virus infections. But why is this useful?

Stephen - This is useful because you can now look at all viruses at one time instead of one at a time which is what people do now. They have to guess you might have been infected with a virus and say, "Okay, check for that one." A lot of viruses - HIV for example or hepatitis C can go unnoticed for a long time, unless someone suspects you've been infected with one of those, they won't even look for it. You can imagine that if there's a simple test that eventually makes it into the clinic that looks at all viruses at once, it could be part of a normal yearly visit to the doctor. We only need a drop of blood - a pin prick will do it - then you could have all of your viruses examined at that time and if you happen to have something that's not good, you can get treatment for it. There are millions of people right now who are chronically infected with hepatitis C and do not even know it.

Chris - But it doesn't tell me anything about when in my life, what age I was when I caught whatever infection because I suppose if one wants to ask, "When did you have infection X" because we're interested in how time relates to different infections occurring at different ages because the impact on your health could be different at different ages, couldn't it? It doesn't really give us any insight into that, does it?

Stephen - No. It could be 2 weeks ago. It could be 2 years ago. It could be 10 years ago. But whenever you find it, you can treat it.

Chris - Stephen Elledge. He published that work this week in the journal Science.

- Previous How sitting harms your health

- Next The Higgs Boson Song

Comments

Add a comment