In 1965 Mars received its first visitor, in the form of the Mariner 4 space probe, which performed a fly-by of the planet and gave scientists a tantalising glimpse of our nearest planetary neighbour.

By this time many of the legends surrounding "canals" on Mars had waned and most realised that the Red Planet was probably a far less hospitable place to inhabit than science fiction authors, or even over-enthusiastic astronomers, were willing to admit.

That said, even with an amateur telescope, Mars reveals hints of surface details that spawn fascination. The dark regions of Syrtis Major, the white polar ice caps or the atmospheric clouds that reveal themselves upon the use of yellow filters, all strongly suggest that there are intriguing scientific treasures waiting to be uncovered on the surface, including the possibility that that life once flourished there, or maybe even still does.

Harsh and forbidding...Whether or not anything lives there now, Mars is certainly a harsh and forbidding world. Sandstorms frequently tear across the surface with sufficient violence to cover the entire face of the planet in a shroud of dust, leaving observers blind to what lies beneath. This is exactly what happened when Mariner 9 arrived in September 1971. Despite orbiting just 2000 km above the planet, the probe was left effectively blind as one of the largest Martian sandstorms ever recorded masked every detail of the planet's terrain. A ringside seat on the planet's surface didn't help much either: a similarly massive storm disabled the Soviet-built Mars 3 Lander shortly after it touched down on the surface in December 1971, a few days after its predecessor, Mars 2, had crashed! To cynics, it seemed the Red Planet was determined not to surrender its secrets!

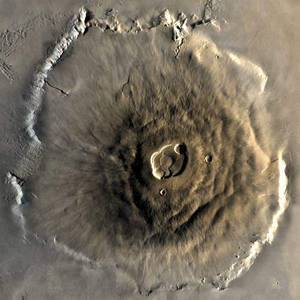

Nevertheless, when the storm abated near the end of 1971, clear skies meant that Mariner 9 was eventually able to gaze upon an awe-inspiring vista of geological features. Huge Martian volcanoes, dwarfing anything ever seen on Earth, could be seen rising from the surface. Among them, Olympus Mons, now known to be the tallest volcano in the solar system, towered 24km above its surrounding plane. Elsewhere on the surface a valley system five times the size of the Grand Canyon, seven km deep and Christened "Mariner Valley" could be seen snaking its way over 4000km into the distance. Our red sister planet, despite being only about a third of the size of the Earth, obviously had a fascinating story to tell. But to understand it, we would need to get much closer.

Subsequent attempts to reach Mars between 1972 and 1974, including several Soviet missions, all met with failure. The first successful touchdown was made in 1975 by Viking 1, followed shortly after by Viking 2.  These probes produced panoramic colour images of the planet and its pink hazy atmosphere, and perhaps the sight of the Sun setting on the Martian horizon rekindled the question of whether there ever had been any life on that desolate yet somehow appealing world.

These probes produced panoramic colour images of the planet and its pink hazy atmosphere, and perhaps the sight of the Sun setting on the Martian horizon rekindled the question of whether there ever had been any life on that desolate yet somehow appealing world.

Viking 1 and 2 had also brought biological tests to Mars with the hope of answering this very question. Unfortunately the results remained, at best, inconclusive, although the data were originally interpreted as negative. After Viking there were no other Mars missions until 1988 when the Soviet space programme took another shot at reaching the red planet. Unfortunately their run of bad luck was not yet over, and Phobos 1 malfunctioned and contact was lost before it ever even arrived. Phobos 2 was more successful and did make it to Mars, but a computer glitch then shut down the craft. Next it was the turn of the US to suffer a setback and their probe, Mars Observer, met its doom three days before orbit insertion.

Thankfully luck was on the side of the next mission, the Mars Global Surveyor, which arrived safely in orbit in 1996 and the subsequent flood of pictures it sent back suggested that there had been substantial amounts of water on Mars in the past. The 1997 US Pathfinder lander subsequently confirmed many of these suspicions and the consensus grew that Mars must have gone through a period in which water was abundant on the surface, and the climate as a whole must have been substantially warmer. Unfortunately, before these questions could be explored further, the 1999 Mars Climate orbiter and the Polar Lander missions were both lost before any useful data could be extracted.

Recent missionsDespite these setbacks, the US's Mars Odyssey mission of 2001, and the 2003 European Mars Express probe, made it to Mars and executed successful research programmes which yielded further corroborating evidence for the presence of water on Mars, even today.

Mars Express, which remains in Mars orbit, has since been producing incredibly detailed images of the planet's surface. Its radar has also picked up signs of large amounts of sub-surface water, and in 2004, shortly after arrival, it also detected traces of Methane in the Martian atmosphere. This was an intriguing discovery because methane should, under the atmospheric conditions found on Mars, be rapidly broken down and turn into water and CO2. But somewhere, and somehow, Mars seems to be replenishing its atmospheric methane. On Earth this is done by active volcanoes, subsurface hydrothermal flows and by life, leading scientists to wonder where the methane is coming from...

To find out, Mars Express dropped a lander module, "Beagle 2", but unfortunately contact was never re-established with the probe, the final resting place of which remains unknown.  But, in 2004, two new US Mars landers, "Spirit" and "Opportunity", successfully touched down on the planet for what was originally intended to be a three month exploratory mission. The two little rovers have now by far exceeded their projected lifetimes, wandering across the planet's surface during "good" periods and returning to their "winter lairs" in bad periods. Amongst their haul of discoveries are pictures of rocks which reveal the effects of flowing water, and broken wheel on one of the rovers recently scraped up a patch of silica, strongly suggesting that Mars once had hot springs or hydrothermal vent systems like those found teeming with life on Earth.

But, in 2004, two new US Mars landers, "Spirit" and "Opportunity", successfully touched down on the planet for what was originally intended to be a three month exploratory mission. The two little rovers have now by far exceeded their projected lifetimes, wandering across the planet's surface during "good" periods and returning to their "winter lairs" in bad periods. Amongst their haul of discoveries are pictures of rocks which reveal the effects of flowing water, and broken wheel on one of the rovers recently scraped up a patch of silica, strongly suggesting that Mars once had hot springs or hydrothermal vent systems like those found teeming with life on Earth.

Life and WaterSo the big questions regarding Mars converge on two issues: 1) Has there been, or is there possibly still, some form of life on Mars, and 2) has there been, or is there possibly still, a substantial amount of water on Mars? I think it is a safe call to say that the latter question has very much circumstantial evidence in favour of a definite "yes". So prospects for life may have been good in earlier times and they may not be as bad as was thought some 25 years ago. To get closer to an answer on the second question a far more detailed chemical and biological analysis in situ is required than has been possible up to date.

The first such attempt is going to be made on May the 26th 2008, with the (hopefully) successful touchdown of "Phoenix" in the arctic region of Mars, where large amounts of (probably frozen) water are suspected. Phoenix will search for this, but also for possible traces of biological activity in the boundary between the arctic ice and the Martian soil.

While Phoenix is making its descent to the surface, Mars Express will focus in on it and keep an eye on this newest lander. The ESA hopes to launch its ExoMars rover around 2013. This probe will carry a drill that can take samples from about two meters beneath the Martian surface. Also in the pipeline, although still in the planning stage but just as exciting, is the European "Mars Sample-return" mission, which could be ready for launch as early as 2011.

Manned missionsPhoenix and the two ESA missions can be considered the final test run for a manned Mars mission. If a sufficient amount of water is available, then sustained human presence on Mars would become a realistic option. Current projections in NASA's Constellation programme and ESA's Aurora programme assume that a human crew would have to stay on Mars for up to 18 months before having a launch window for a return mission. The prime reason for this is that to reduce risks from exposure to cosmic rays and solar flares it is best to minimize the in-flight time of a human crew. Such "fast" orbits are available roughly once a year and take the one-way trip would take about 6 months. Supplies and consumables would then need to be sent ahead of the crew on a longer duration trajectory that, as it is energetically more favourable, allows the transportation of greater payload to Mars. For such a manned Mars mission to become a realistic option there would need to be water there.

Comments

Add a comment