'You may, therefore, market the device, subject to the general controls provisions of the act.'

These words announced the decision to allow commercial marketing of leeches in the United States by the French company Ricarimpex. (FDA Consumer magazine, September-October 2004 issue).

In the classic movie 'The African Queen', Humphrey Bogart quivered in horror when he saw the leeches attached to his torso. The director, John Huston, obviously knew how to make an audience squirm. But this image of the leech as something slimy that sticks to you in the jungle has always been counterbalanced by a curious benefit.

In the classic movie 'The African Queen', Humphrey Bogart quivered in horror when he saw the leeches attached to his torso. The director, John Huston, obviously knew how to make an audience squirm. But this image of the leech as something slimy that sticks to you in the jungle has always been counterbalanced by a curious benefit.

According to the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) the new, modern leech is a medical device. This is not as bizarre as it seems - if you supposed leeches were an ugly aspect of medical superstition, think again. In fact, leeches have been in regular use for medical purposes and the recent decision by the FDA merely satisfied a legal requirement to clear new applications to sell them - the first since the 1976 law was enacted.

Leeches are segmented worms (like earthworms) that have developed a parasitic lifestyle by feeding on the blood of other animals. For this purpose the leech has an exquisitely adapted mouth: 3 jaws and hundreds of tiny teeth which reputedly leave a bite mark shaped like a Mercedes-Benz symbol.

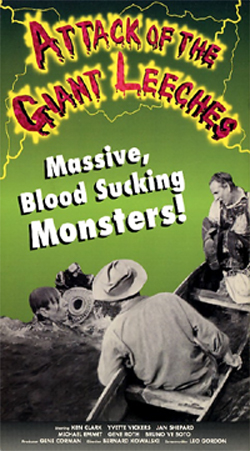

There are scores of different types of leech including the giant 'two pints today, please' amazonian leech (see the American Museum of Natural History website listed below), big enough to give you the creeps but not exactly the blood sucking monster of B-movie fantasy. Fortunately, the smaller European cousin - Hirudo medicinalis - is the one predominantly used for modern medical applications.

Application of leeches reached a peak of popularity - with doctors if not patients - in the 19th century. The use of leeches is a very ancient practice; they appeared in the tomb paintings of Egyptian pharaohs more than 3000 years ago.

A later justification for leech therapy arose from the classical Greek theory of bodily function which involved humors (good and bad) contained in the blood. Conditions such as inflammation and fevers were considered to result from bad humors. The humoral theory required bleeding to drain these bad humors, so the use of leeches represented one aspect of the widespread practice of bloodletting. The leech was simply a medical device to remove bad humors.

Closer to home, we can see clues to the use of leeches in the Old English word for a healer, laece (meaning leech). This association with healing also explains why old books of remedies were known as leechbooks.

One of the principal modern uses of leeches is during the recovery from reconstructive surgery. Two different areas of biomedical research have made this possible. The first is knowledge of the response of human tissue to transplantation and the blood supply requirements that are necessary. The second is a refined understanding of how the leech is able to draw large amounts of blood from a host.

One of the principal modern uses of leeches is during the recovery from reconstructive surgery. Two different areas of biomedical research have made this possible. The first is knowledge of the response of human tissue to transplantation and the blood supply requirements that are necessary. The second is a refined understanding of how the leech is able to draw large amounts of blood from a host.

The removal of blood in grafted tissue after surgery can be slow because the normal circulation has been disrupted.

Blood vessels which bring blood into the damaged tissue may continue to work as normal, but the veins which carry blood away from the site of surgery are easily blocked by small blood clots that form in the area. This leads to a pooling of blood known as venous congestion. Without a normal blood circulation this venous engorged tissue may not survive or could develop gangrene.

Leeches help venous engorged tissue in several ways. Not only does their feeding remove the congested blood, but the saliva of the leech contains a natural chemical that stops blood from forming a clot (an anticoagulant). Without any clotting, blood flows more freely within the damaged tissue - and, naturally, from the host to the leech. This anticoagulant no doubt prevents leech indigestion by stopping the blood from forming a solid lump in their expanding stomach.

A further human benefit is that the anticoagulant continues to work in the wound for some time after the leech has dropped off. The result is that veins are no longer blocked by small clots and the improved circulation nourishes the area of injury. Reattachment of severed fingers, ears, lips, noses or skin flaps have all been noted to benefit from this procedure.

Leeches, garlic and death Haven't you ever wondered what happens when you dip leeches in beer? No? Well apparently their behaviour changes; they sway their forebodies, behave erratically and fall over. Not so surprising perhaps, but what is the point of this you might wonder? Testing garlic on leeches is more obvious; after all, the most famous bloodsucker of them all is supposed to dislike the stuff (which explains why Dracula could never have been Italian). In a small study, the mere touch of a garlic-smeared arm caused a 100% death rate among the subjects (both leeches died). Perhaps Bram Stoker knew a thing or two about leeches? Adapted from; A. Baerheim & H. Sandvik (1994). British Medical Journal vol. 309, p 1689. The same team brought you the exposé about protective measures against 'earth rays' - available in the original Norwegian. |

Blood clots are the normal reaction to tissue damage; they are formed at the end of a series of biochemical steps. The last step is the production of an insoluble protein called fibrin, which requires an enzyme called thrombin.

Small fragments - called platelets - of larger blood cells also get attracted to sites of injury by the chemicals released from injured tissue. Fibrin and platelets get stuck to the tissues around a wound and form a plug of material.

Various chemicals (mostly small proteins) in leech saliva attack different stages in the process of blood coagulation.

One chemical - called hirudin - interferes with the function of thrombin and so prevents the sticky protein fibrin from being made. Other components of leech saliva have been identified which stop platelets from gathering at the site of injury or prevent them from sticking normally at the site of damage.

Curiously, leeches on your body are often discovered only some time after they have begun to feed. Although this has been attributed to some anaesthetic contained in leech saliva, there is no obvious candidate which can explain the failure to feel the pain of a bite. But with up to 100 different proteins in leech saliva, there are plenty of untested candidates.

The potential of hirudin for the treatment of heart or circulatory problems has been a stimulus to find sources of this drug which do not rely on the leech supply.

Now hirudin can be produced from yeast which have had the hirudin gene inserted into their DNA. This recombinant hirudin, along with the production of synthetic look-alikes (structural analogues), is giving greater means to explore the implications of leech therapy.

In the future, leeches themselves could be replaced by our penchant for automation. While the leech is very good at local application of anticoagulant, they do have a tendency to wander around and may re-attach themselves at locations that are either inconvenient or downright alarming.

Something to ponder if you're having a bit of nip 'n tuck in the nether regions - keep the salt water enema handy. The solution to this lies in the development of a mechanical leech, which apparently also has less 'yuck' factor. Personally, I'm not convinced Roboleech is necessarily more comforting. It might be less likely to wander off, but I wouldn't let bored medical staff spend too long with the remote control...

- Previous MACHINA - An Overview

- Next Hubble Space Telescope

Comments

Add a comment