Antibacterial vegetables capable of blitzing dangerous E. coli infections have been bred by scientists in  Germany.

Germany.

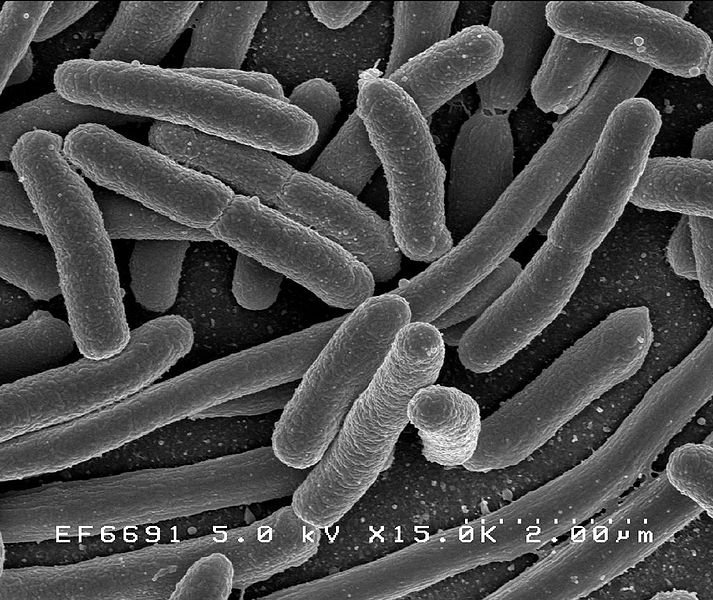

Although E. coli is a universal resident of the human intestine, some forms of the bacterium, including those dubbed EHECs - enterohaemorrhagic E. coli - which are carried by livestock, can cause life-threatening infections.

The bugs can be passed on to people in contaminated foodstuffs such as meat, or even in vegetables grown in ground fertilised with animal slurry.

An E. coli O104:H4 outbreak that caused thousands of infections across Europe in 2011 was traced to a batch of contaminated fenugreek seeds.

Remarkably, part of the solution to stopping outbreaks like this might lie with E. coli itself.

For more than 90 years, scientists have known that some strains of these bacteria produce chemicals called colicins, which selectively attack and disable other E. coli. They work by attacking genetic and other biochemical susceptibilities present in some forms of E. coli and their close relatives.

Writing in PNAS, Nomad Bioscience researcher Steve Schulz and his colleagues have successfully moved the genes encoding 12 colicins from their E. coli parents to a range of plants including tobacco, spinach and beets.

The result is plants capable of producing very high levels of the colicin products. In tests, yields of 3 grams per kilogram were achieved.

The colicin proteins were easy to extract from the plants in a fully functional form and, individually or in combination with each other, were capable of neutralising all of the "big 7" E. coli strains identified as capable of causing EHEC syndromes. The O104:H4 European strain was also susceptible.

Extracts added to meat samples that had been contaminated with E. coli showed up to 1000-fold lower levels of the bacteria after a short incubation period at fridge-temperatures compared with controls. The level of bacterial inactivation also continued to increase with time, suggesting that the approach could work well to suppress the growth of bacteria on stored meats.

Reassuringly, experiments also showed that the colicins would be deactivated rapidly by digestive juices, preventing any effects on an individual's native gut flora.

Moreover, the human gut already contains E. coli strains capable of producing colicins, meaning that this class of chemicals fall under regulatory legislation dubbed "GRAS" - short for "generally regarded as safe".

This means that the product candidates would be approved for healthcare use relatively quickly. And as they are not antibiotics but instead natural compounds, they avoid the on-going risks associated with antimicrobial resistance.

Comments

Add a comment