Australian scientists have used cochlear implants to deliver hearing-restoring gene therapy treatments to the inner ear.

Invented in Australia, the cochlear implant  is one of the most successful bionic implants ever developed.

is one of the most successful bionic implants ever developed.

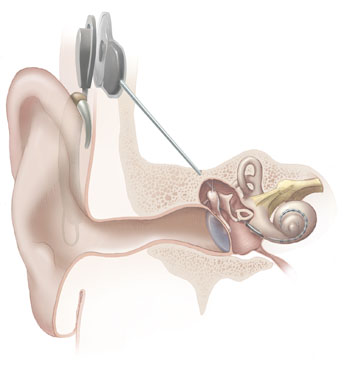

The device consists of a series of tiny platinum electrodes, which are threaded into the cochlea, the head's hearing organ.

They deliver tiny electrical pulses which directly activate the nerve cells that signal to the brain the presence of different sound pitches. In this way the implants replace the role of "hair" cells that normally do this job and which can be lost owing to toxic, genetic or environmental factors, particularly noise exposure.

But the electrical nature of the cochlear implant means that it can also, scientists have now shown, be used for gene threapy, triggering tissues in the inner ear to pick up chunks of DNA including genes encoding growth factors that can improve residual hearing functions.

Writing in Science Translational Medicine, UNSW researcher Gary Housley and his colleagues have shown that deaf guinea pigs implanted with animal versions of cochlear implants and injected in the inner ear with a gene encoding a growth factor called BDNF, show significant restoration of their hearing sensitivity compared with control animals.

Examining the cochleas of the treated animals showed that electrical impulses from the implants provoked cells in the ear to pick up the injected DNA, then synthesise and release the growth factor.

This, they found, triggered the nearby sound-sensitive nerve cells to put out denser nerve branches, increasing their ability to pick up auditory signals from the implant.

The team emphasise that these results are preliminary and at present have only been shown in their experimental guinea pigs, but extrapolated to humans could lead to significant improvements in cochlear implant function and could become a routine procedure carried out when implants are first installed.

The long-term effect of the therapy, however, still needs to be explored, alongside the co-administration of genes encoding other growth factors, which might boost the regenerative effects of the therapy.

- Previous Plane Stowaway

- Next Corals can acclimatise

Comments

Add a comment