Nature has inspired researchers to make brighter, more efficient LEDs, by copying the structure of a firefly's rear end.

Writing in the journal PNAS, Ki-Hun Jeong and colleagues at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology noted that fireflies rely on having bright, coherent lights, or lanterns, in order to find a mate.

We can assume that there would be an evolutionary pressure to make the light as bright as possible for the least energy consumption - those who could outshine others would be more likely to find a mate, and the more efficient the process, the more likely they would still have the energy to do something about it when they do find one.

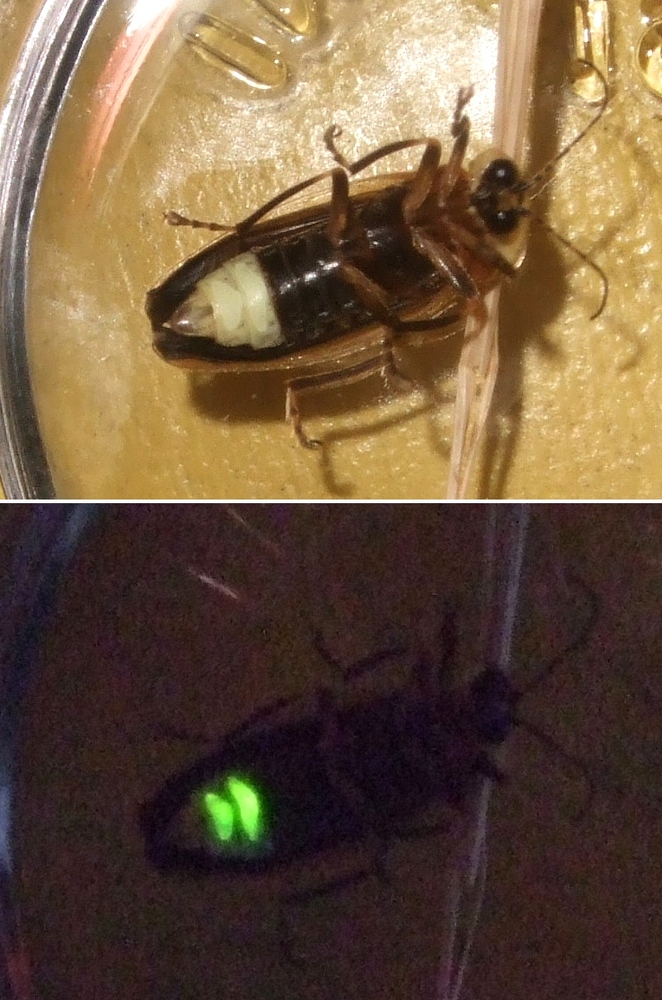

The biochemisty of firefly light production, bioluminescence, is well understood - an enzyme called Luciferase acts on a chemical called luciferin, causing it to emit a yellow light. But how this light then escapes the lantern, the light producing organ, is not well studied. So, to find out how Nature makes the most of this reaction, the researchers looked at the nanoscale structure around a firefly's lantern using electron microscopy.

The biochemisty of firefly light production, bioluminescence, is well understood - an enzyme called Luciferase acts on a chemical called luciferin, causing it to emit a yellow light. But how this light then escapes the lantern, the light producing organ, is not well studied. So, to find out how Nature makes the most of this reaction, the researchers looked at the nanoscale structure around a firefly's lantern using electron microscopy.

They saw that the surface layer, or cuticle, was very different around the lantern compared with the rest of the abdomen. Over most of the body, the surface layer was amorphous, and had no identifiable structure or pattern. Around the bioluminescent organ, however, the outer layer was ordered in neat rows. On further investigation, they realised that this structure was reducing the difference in refractive index between surface and air, reducing the amount of refraction and scatter, and therefore allowing more of the light to shine outwards.

In an example of biomimetic design, the researchers then manufactured LEDs with a similar nano-ridged curved surface layer across the top. They then compared the intensity of light given out by these adapted LEDs with similar LEDs that had a smooth surface layer.

The firefly inspired LEDs were consistently brighter than the normal counterparts, with an increase of up to 3%, across a range of light colours. To get that sort of increase from an LED today, you need to invest in expensive anti-reflective coatings. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the frequency of light best transmitted matched the yellow light of the firefly.

A 3% increase may not sound like much, but it could see a cut in electricity bills, and will spur the development of low-cost, high efficiency LEDs for domestic, commercial and automobile lighting; hand held devices, and screens for LED televisions and monitors.

Comments

Add a comment