A gene that adds two years to your appearance has been documented by scientists studying people in the Netherlands and the UK.

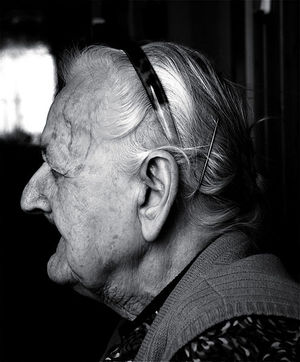

Looking young for your years is regarded by many as a sign of vitality, vigour, fecundity and health and is a highly sought-after trait, both now and throughout history.

But new research suggests that there's only so much that a healthy diet, not smoking and avoiding sun beds can achieve, because a study has now highlighted a gene that can make you look more decrepit than you really are.

Unilever researcher David Gunn and his colleagues scrutinised the genomes of several thousand Dutch and UK subjects using an approach called genome wide analysis.

The researchers were looking for genetic letter combinations called SNPs - single nucleotide polymorphisms - which act like molecular signposts, flagging up regions of the genome linked to a particular trait.

The appearances of the participants had been rated for their apparent ages by an independent group of assessors.

These ratings were then married with the SNP profiles for each individual to look for repeated "hits" in certain parts of the genome.

A very strongly relationship emerged for a gene called MC1R. This is known as the melanocortin receptor gene and plays a role in controlling the composition of melanin, the dark pigment found in skin.

People with one form of the gene tended to look older, on average, than people with a different form.

And if an individual had both copies of the gene (one from their father and one from their mother) of this type, the individual was rated as 1.8 years older than someone not carrying any copies of this form of the gene.

The effect was still apparent when the researchers controlled for other factors such as skin pigmentation marks and wrinkles, so it's clearly having an effect beyond these two factors, although at this stage the team do not know why.

They also point out in their paper in Current Biology that the overall sample size they have considered is relatively small and they now need to widen the scope of the study to make it more powerful so that more subtle relationships may be detected.

- Previous Are morning vaccines more effective?

- Next Decoy eggs to trap sperm

Comments

Add a comment