A group led by Daniel Janies from the Ohio State University have used molecular sequencing, developmental data, and supercomputers from the Ohio Supercomputer Centre to solve a taxonomic problem involving echinoderms...

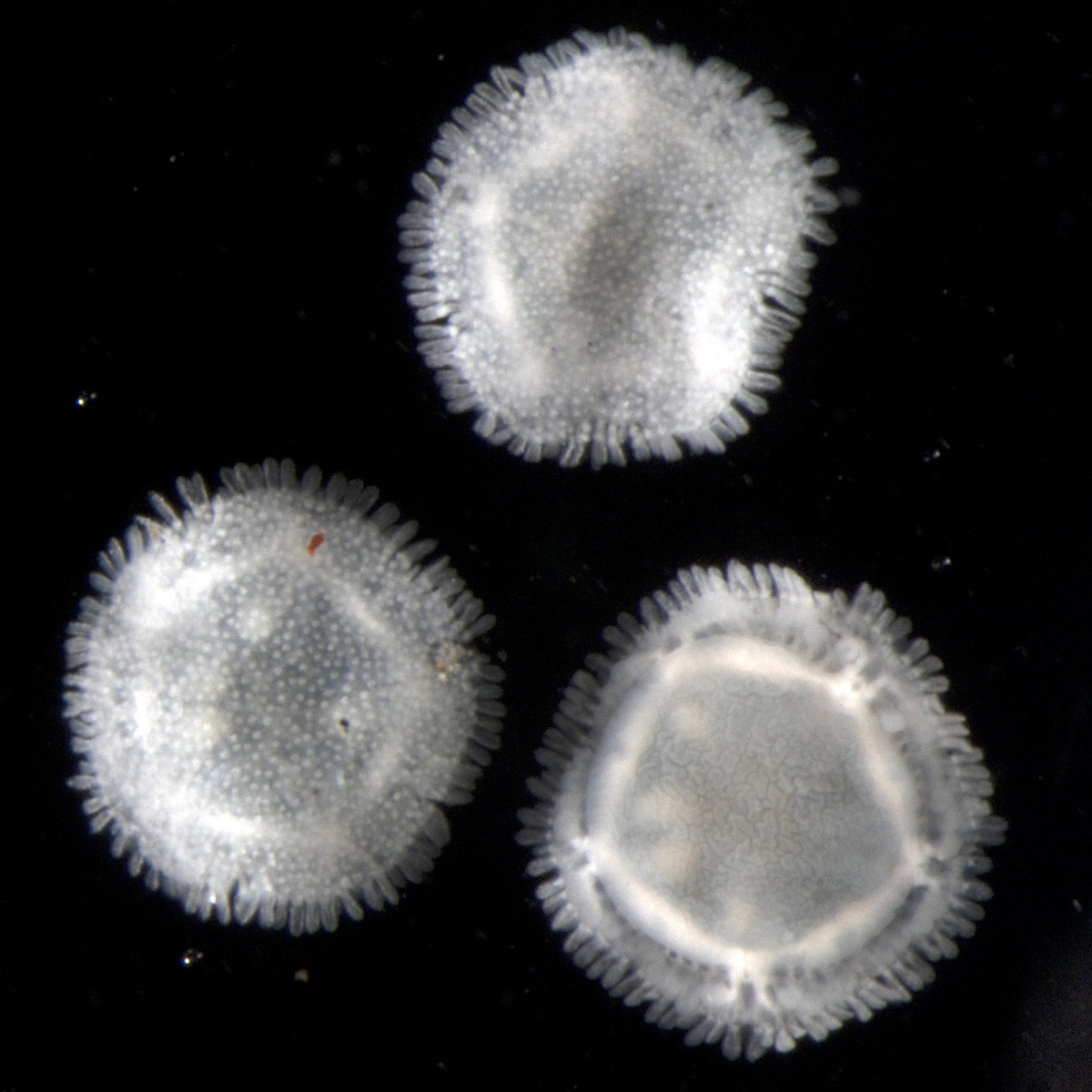

Echinoderms include creatures like sea urchins, starfish, sea cucumbers and sea lilies. But how the different classes of living echinoderms are related to each other has caused problems over the years, with one particular deep sea specimen giving taxonomists a headache. It's called Xyloplax, and it's a tiny, disc shaped animal, about 4mm across, found in the deep sea around New Zealand and the Bahamas. It didn't fit with the body plans of other groups, so it was placed in a separate class of its own - a sixth echinoderm class, alongside Asteroidea (which are the starfish), Ophiuroidea (including brittle stars), Holothuroidea (which are the sea cucumbers), Echinoidea (sea urchins) and Crinoidea (the sea lilies).

But now a group led by Daniel Janies from the Ohio State University have used molecular sequencing, developmental data, and supercomputers from the Ohio Supercomputer Centre to show that actually, Xyloplax belongs within the Asteroidea, with the starfish. They examined specimens caught by Janet Voigt, another of the paper's authors, to show that Xyloplax broods its young in a special chamber, just like other groups of starfish, and study its development. And they were able to extract genes from the specimens to compare with 86 other echinoderm species and non echinoderm outgroups, to create a phylogenetic tree, which places Xyloplax with the starfish.

But why doesn't it look like a starfish?  Well, Janies and his colleagues suggest Xyloplax's circular appearance is due to a process called progenesis, where individuals reach sexual maturity whilst retaining their juvenile body plan. Progenesis, along with another process called neoteny, are examples of paedomorphosis, where adults of a species either retain features of juveniles (in neoteny - an example of this would be the external gills on an axolotyl) or completely retain the juvenile body plan, whilst being sexually mature, which is progenesis, as is the case here. There aren't that many robust examples of paedomorphosis in nature, but it has been suggested as a route that vertebrates could have evolved by, and in human evolution too. So having more examples of it will hopefully allow us to understand it better.

Well, Janies and his colleagues suggest Xyloplax's circular appearance is due to a process called progenesis, where individuals reach sexual maturity whilst retaining their juvenile body plan. Progenesis, along with another process called neoteny, are examples of paedomorphosis, where adults of a species either retain features of juveniles (in neoteny - an example of this would be the external gills on an axolotyl) or completely retain the juvenile body plan, whilst being sexually mature, which is progenesis, as is the case here. There aren't that many robust examples of paedomorphosis in nature, but it has been suggested as a route that vertebrates could have evolved by, and in human evolution too. So having more examples of it will hopefully allow us to understand it better.

Comments

Add a comment