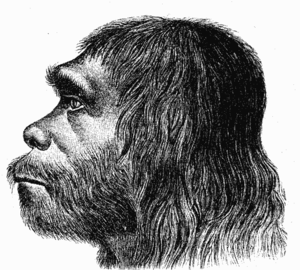

A couple of weeks ago on the show we discussed the science of archaeogenetics - unravelling the mysteries of the past in our genes. This week there's been an important step forward in the field, with the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome, published in the journal Science. The new research helps to answer some puzzles, such as did humans and Neanderthals ever mate, and how many genes we share.

The scientists used samples of bones from three female Neanderthals who lived in Croatia more than 38,000 years ago. Then they used the latest DNA sequencing technology to sequence the DNA and build a composite genome - they've got around 1.3-fold coverage, although around a third of the genome is still a bit unclear. Then came the fun stuff - comparing the Neanderthal sequence to the genomes of humans living in different parts of the world today.

The scientists used samples of bones from three female Neanderthals who lived in Croatia more than 38,000 years ago. Then they used the latest DNA sequencing technology to sequence the DNA and build a composite genome - they've got around 1.3-fold coverage, although around a third of the genome is still a bit unclear. Then came the fun stuff - comparing the Neanderthal sequence to the genomes of humans living in different parts of the world today.

Intriguingly, the team, led by Svante Paabo from Germany, discovered that modern Europeans and Asians share between 1 and 4 per cent of their DNA with Neanderthals - but Africans don't. This tell us that any interbreeding between us and them happened after modern humans had left Africa, but before they spread across Asia and Europe, perhaps around 30,000 to 45,000 years ago - maybe even as early as 80,p000 years ago in the Middle East. So many people in Europe and Asia have a small but significant Neanderthal component in their genes - including Paabo himself.

The scientists have been comparing the Neanderthal genes with those of present-day humans to try and find the key genes that make us modern - we are around 99.84 per cent identical, but there are some crucial differences. At the moment the significance of the results isn't completely clear, but there are a number of intriguing differences in genes involved in metabolism, skin, bones and brain development, but we don't know how these relate to physical properties.

The research also allows us to speculate a bit as to how Neanderthals and humans might have interacted together. The researchers think that just a few Neanderthals infiltrated a group of humans, and started interbreeding, rather than a mass mixing of the two species. We don't know why they kept themselves mostly separate, now that we know there was no biological barrier to interbreeding - perhaps there were significant cultural differences? For now, there's still a lot more work and analysis to do, but this new genome gives us an intriguing look into our genetic past. And maybe many of us have a little bit more Neanderthal in us than we might have thought.

- Previous Untangling triple negative breast cancer

- Next E. coli vaccine?

Comments

Add a comment