"...fava beans and a nice Chianti, f-f-f-f-f-f!", uttered the iconic character, Hannibal Lecter.

But similar psychopaths might have to enjoy liver and beans without the trappings of Italian wine in future because a  previously-unknown alien moth species has begun attacking vineyards in the country's Northern provinces.

previously-unknown alien moth species has begun attacking vineyards in the country's Northern provinces.

The leaf-mining moth lays its eggs on vines. When these hatch, the emerging larvae eat the leaves, damaging the vine's growth and reducing grape yields.

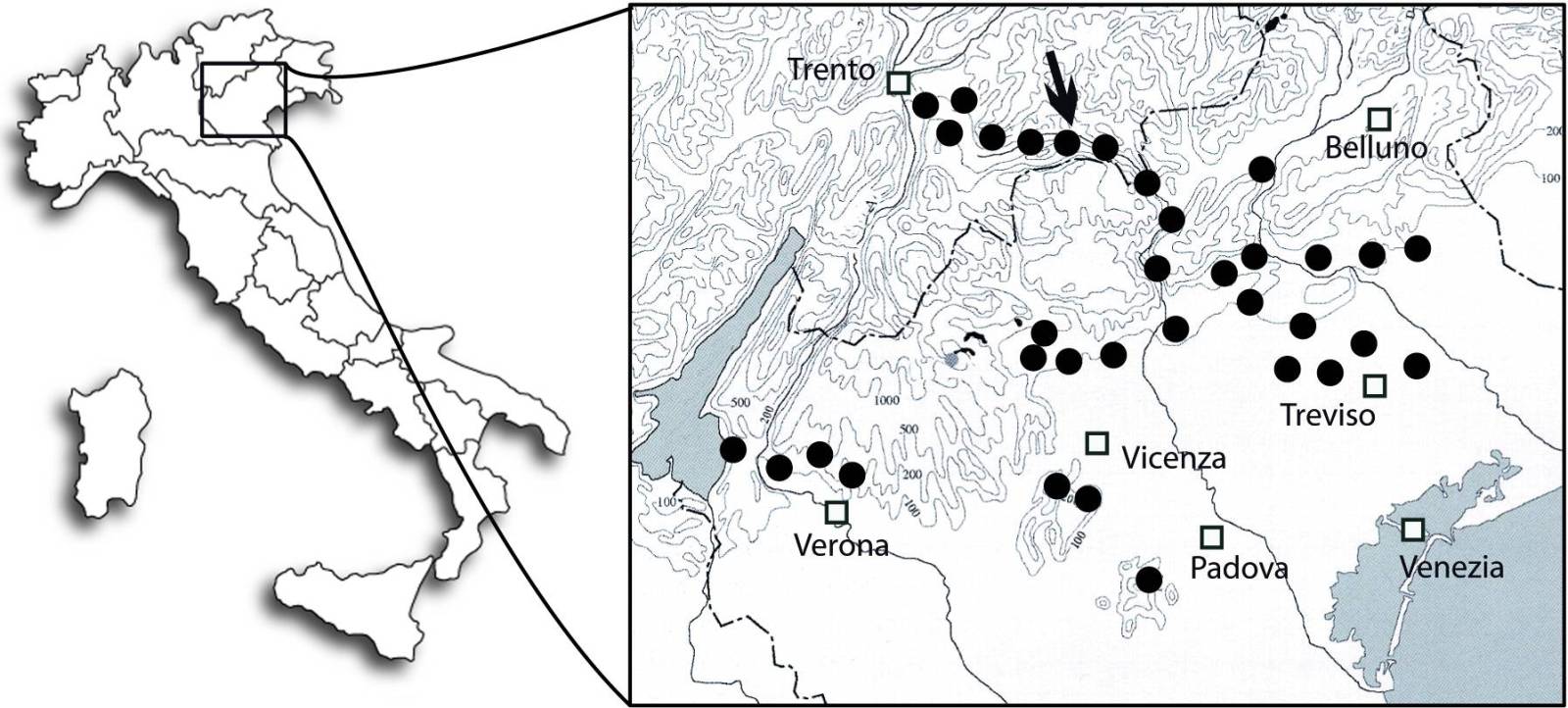

The moths were first spotted in Italy in 2006 and now relatively heavy infestation rates of 5 larvae per leaf are being picked up in affected areas around Trento, Vincenza and Verona.

The pest was at first mis-identified, but a team of Italian, Dutch and American scientists showed it to be a new species belonging to the leafminer family called Antispila oinophylla. The real shock though is that this species, despite being discovered in Italy, did not originate there.

"When we analysed the DNA barcodes, we found many more species ... in North America!" explains Dr Erik van Nieukerken, author of the study published in the journal Zookeys.

This means that the moths had somehow invaded Italy from across the Atlantic, although exactly how these globe-trotters crossed the pond remains a mystery. van Nieukerken thinks it's down to a combination of biology and technology.

"Leafminer larvae live in small protective 'shields' where they can survive cold winter temperatures for periods of up to 7 months. They often attach these shields to plant parts, stems or debris so the shields could be rather easily transported," van Nieukerken explains. And with the frequency of modern traffic, "even adult moths could be easily transported and it takes just a few specimens, or even a single pregnant female, to start a new population. The number of new introductions shows that such things happen all the time."

traffic, "even adult moths could be easily transported and it takes just a few specimens, or even a single pregnant female, to start a new population. The number of new introductions shows that such things happen all the time."

Such manmade pest invasions are happening increasingly frequently as global trade and transport intensify. For example, three rat species have spread worldwide aboard boats, and larvae of Russian zebra mussels, borne in the ballast water carried by ships to Europe and America have, established the species in these new geographies. Unchallenged by predators in their new homes, the mussels grow and reproduce with devastating speed, clogging up intakes at water treatment works and power plants and even obstructing harbours and waterways.

Perhaps it's not surprising, then, that the trans-Atlantic trade in invasive moth species is not a new phenomenon. In 1868, a French scientist accidentally introduced the gypsy moth into the eastern USA. It bred  slowly for a century before beginning to strip the leaves from American forests at an alarming rate. About 300 million US dollars has so far been spent attempting to control the problem since the first major outbreaks in the 1980s. Alas, the gypsy moth remains a major pest of hardwood trees and is still spreading westwards across the country. The US Forest Service is using sprays to control the moths across large areas of forest and have even introduced a natural moth enemy in the form of a Japanese parasitic wasp called Ooencyrtus kuvanae. These lay eggs inside moth larvae. Hundreds of young wasps then develop inside the moth, compromising its growth and development.

slowly for a century before beginning to strip the leaves from American forests at an alarming rate. About 300 million US dollars has so far been spent attempting to control the problem since the first major outbreaks in the 1980s. Alas, the gypsy moth remains a major pest of hardwood trees and is still spreading westwards across the country. The US Forest Service is using sprays to control the moths across large areas of forest and have even introduced a natural moth enemy in the form of a Japanese parasitic wasp called Ooencyrtus kuvanae. These lay eggs inside moth larvae. Hundreds of young wasps then develop inside the moth, compromising its growth and development.

So has Italian Chianti popped its final cork or is there hope? The evidence is that the game's not over yet, with some even suggesting Italian vine growers could follow America's lead and introduce a similar parasitic wasp. Moreover, this body-snatching mode of population control is bound to find favour with Dr Lecter, not least since he's also likely to hang onto his Chianti too...

Comments

Add a comment