Nanoparticles that can arrest the process that leads to narrowed and blocked arteries have been developed by scientists in the US.

More than one person in three will fall victim to arterial disease, known as atherosclerosis, which is linked to heart attacks and strokes.

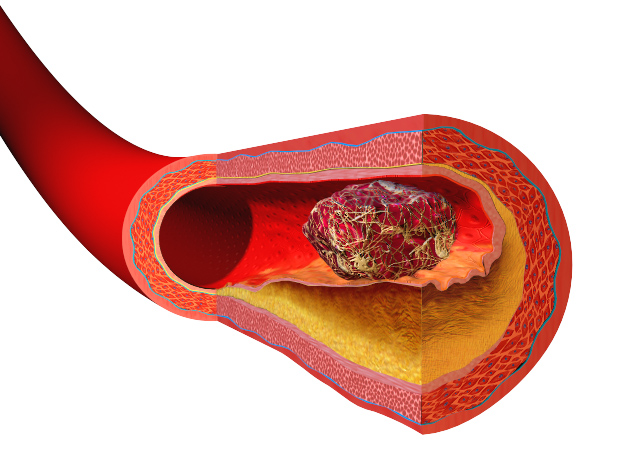

Fatty deposits rich in cholesterol and dubbed "atheroma", accumulate in the walls of arteries, obstructing the flow of blood and starving the tissue downstream of oxygen and nutrients.

These so-called plaques, which grow slowly as they steadily accumulate more fat from the bloodstream, can also rupture, leading to sudden blockage of the blood vessel and a stroke or heart attack.

Present strategies to prevent this from happening include control of blood pressure, diet and body weight, not smoking and, in people with high blood cholesterol, drugs like statins.

Now, writing in PNAS, Rutgers researcher Prabhas Moghe has developed a nanoparticle-based approach that, at least in mice with the rodent-equivalent of arterial disease, can dramatically slow the disease process.

The particles, which are based on a chemical called PEG - polyethylene glycol - that is know to be well-tolerated in the body, target cells called macrophages. These build up inside arterial plaques and soak up fats and cholesterol using a chemical receptor on the surface of the macrophage that locks on to the fat molecules to pull them into the cell.

"The nanoparticles mimic the part of the cholesterol molecule that the macrophage is looking out for," explains Moghe. "So they get in the way, which stops the fats accumulating, and this prevents the arterial plaques from growing." Sure enough, one month later, mice treated with the nanoparticles had 37% less arterial narrowing, on average, compared with untreated controls.

The nanoparticles could also be traced afterwards to diseased parts of the animals' blood vessels, providing evidence that their physical presence was what was influencing the disease in these animals.

There is, however, some way to go yet before a human can roll up a sleeve for an anti-atheroma shot. Mice are very short lived compared with a human, so it's not clear whether the particles strategy would work on the much longer timescale of a human life.

It's also unclear how frequently they would need to be administered, or what the side effects might be. Moghe is optimistic all the same. "The particles break down to form harmless substances that are excreted naturally from the body," he says.

Comments

Add a comment