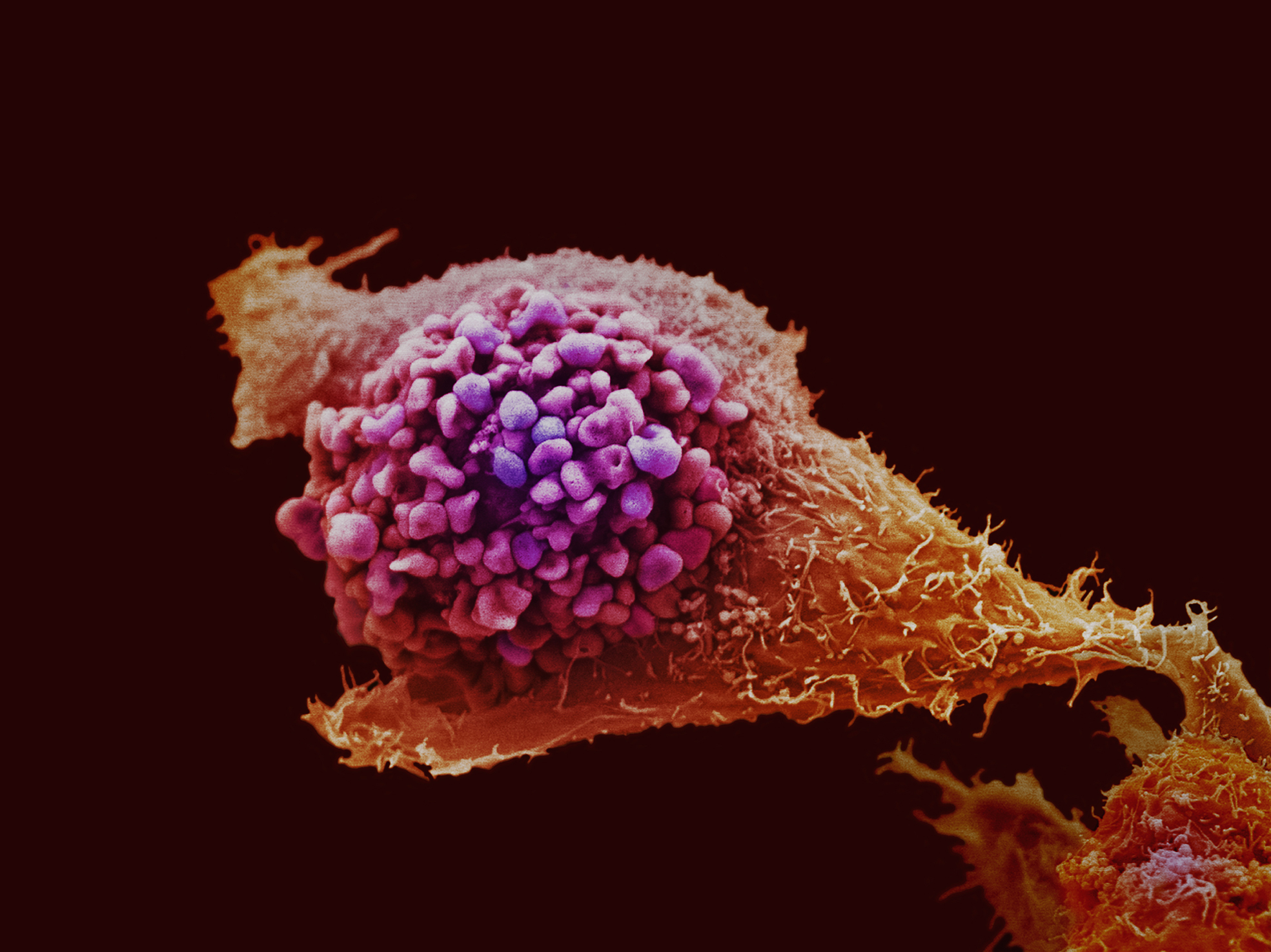

Cancer is a disease caused by cells multiplying out of control. It's been known by many names through history - some of them unrepeatable on air, from people and families who've been affected by the disease. One ancient name is "the wound that does not heal", and today, researchers are uncovering many similarities between the controlled cell production required for wound healing, and how this process is hijacked in cancer.

Now new results from a Cancer Research UK-funded team led by Professor Alison Lloyd at University College London have found an important link between nerve repair and how tumours may spread within the nervous system, and they've just published their findings in the journal Cell.

Our nerves are actually pretty good at repairing themselves, although it doesn't always work in the case of severe damage or crushing. For example, nerves can grow back through deep cuts, and it's possible to reattach amputated fingers, toes and even limbs, and have some regrowth of the nerves. And this is all down to special cells called Schwann cells.

Schwann cells act a bit like insulation around nerves - like the plastic coating around electrical wires. Normally, they help the speed up nerve signals, but we know that they're also really important for directing repair.

When a nerve is cut, Schwann cells start growing out into the wound, and start making "guide tracks" for the nerves to grow along. And here's where the new research from Professor lloyd and her team comes in, as they've uncovered some of the complex molecular signals that control the process.

The researchers were looking at exactly how the Schwann cells are controlled and directed into these "guide tracks" by fibroblasts - repair cells that gather at the site of a wound. The team discovered that fibroblasts produced a 'signal' molecule called ephrin B, which is received by 'receptor' proteins on the surface of the Schwann cells called EphB2, standing for Ephrin receptor B2.

It's this ephrin signalling that tells the Schwann cells to organise themselves into tracks, as directed by the fibroblasts, so the nerves can regrow, a bit like traffic police using special hand signals to direct cars into different queues on a road.

And, importantly, the scientists found that switching off ephrin signalling meant that Schwann cells couldn't repair nerve damage, proving that it's a fundamental part of the process. So these findings tell us something important about nerve repair, which will be useful for researchers working on techniques such as nerve grafts, which could repair damaged nerves after accidents or surgery.

So how is this linked to cancer? Well, we know that some types of cancer can spread along nerve cells - and the way they do this looks very similar to the way that the Schwann cells and fibroblasts move as they repair damaged nerves, and it's likely that the same ephrin signalling is involved.

Professor Lloyd thinks that cancer cells may be acting a bit like an unhealed wound, hijacking the signals that normally repair nerves. In a normal situation, the regrowth signals would be switched off when the nerves have grown across the wound. But in cancer, it may be that the signals don't get switched off and the cancer cells carry on spreading along the nerves, rather than ever settling down and 'healing'.

So understanding how this signalling goes wrong, and how we can block it, could prove to be an interesting lead for future treatments that stop cancer from spreading.

Comments

Add a comment