A promising new therapy for multiple sclerosis, an inflammatory disease  of the nervous system that progressively robs sufferers of their faculties, has been awarded prize funding for a preclinical trial.

of the nervous system that progressively robs sufferers of their faculties, has been awarded prize funding for a preclinical trial.

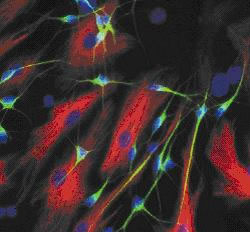

Multiple sclerosis (MS) affects about 1 person in a thousand. The condition occurs when the immune system attacks a material called myelin that is wrapped around nerve cells like the insulation around an electrical wire. Denuded of its protective myelin covering, affected nerve cells fail to transmit information correctly and ultimately die.

The mainstay of current MS therapies is suppression of the immune system to prevent further attacks on brain and spinal cord myelin.

However, deactivating the immune system in this way has severe side effects, rendering the patient vulnerable to infection. It also does not alter the ultimate course of the disease.

In recent years however, working on mice with the rodent equivalent of MS, scientists have discovered that a signalling molecule called LIF - leukaemia inhibitory factor - can be used to stop the disease and even promote repair, reversing some of the previous damage.

Now a Cambridge scientist has developed a new LIF-based therapeutic that can deliver the chemical selectively to sites of MS damage via a nasal spray.

The breakthrough, which has earned its inventor, Su Metcalfe, a Merck-Serono prize to run a preclinical trial into the therapy, uses nanoparticles fashioned from the same material - a tissue-friendly substance called polyglycolic acid - that is employed in dissolvable sutures.

The LIF is impregnated into the nanoparticles, which are also coated with an antibody that recognises the cells in the brain present at sites of MS-associated inflammation and damage.

This means that, when they are administered, either by being injected into the bloodstream or even via a nasal spray, the particles home in on the areas where the disease is active and steadily unload their LIF cargo as they dissolve. This deactivates the immune cells that are attacking the myelin. It also stimulates stem cells that are also present, encouraging them to grow and replace the missing myelin.

"There are very good models of MS in mice now," says Metcalfe. "And administered to these animals, the treatment works." There also shouldn't be side effects. "The LIF treatment is delivered just to the places that need it and not anywhere else because the particles won't stick elsewhere."

She plans to use the funding from her Merck-Serono prize, which has never previously been awarded to a UK scientist, to initiate a pre-clinical trial of the approach so that, within two years, she says, it should be feasible to take the treatment into human patients. "Then we'll have something that can actually repair damage as well as stop the disease. Nothing else can do that at the moment."

Comments

Add a comment