US Scientists working on HIV have uncovered a viral Achilles heel that might aid in the develop of a vaccine.

Writing in Science, Scripps Institute researcher Dennis Burton and his colleagues have been combing through more than 1800 blood samples from patients in Australia, Africa, Asia, Europe and the US looking for signs of antibodies, termed broadly neutralising antibodies, that can inactivate HIV.

'By first finding antibodies that can inactivate HIV, we can then work out which part of the virus they're targeting and then use that very component as a vaccine,' Burton explains.

'By first finding antibodies that can inactivate HIV, we can then work out which part of the virus they're targeting and then use that very component as a vaccine,' Burton explains.

Previous attempts to carry out this line of investigation have yielded only antibodies that target relatively inaccessible components of the virus, making it very difficult to incorporate them into a vaccine. But now, with new technology and an updated approach, the team have immediately struck gold with their first patient and uncovered two new antibodies, dubbed PG9 and PG16, which can block the virus from invading and infecting cells.

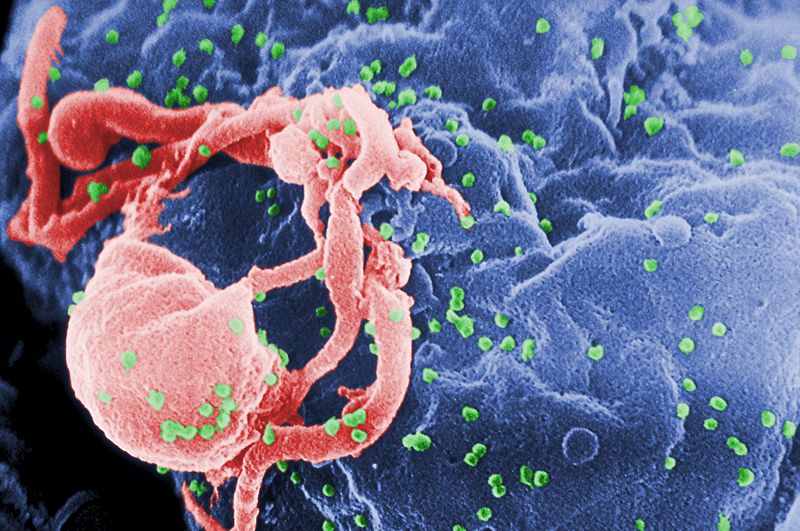

By making mutant viruses with slightly differing surface structures and testing the newly-discovred antibodies against them, the team have also worked out that PG9 and PG16 target the spike proteins (gp120 and gp41) that decorate the surfaces of HIV particles. The virus uses these spikes like molecular velcro to enable it to recognise and infect immune cells, a process that the antibodies can disrupt.

'Critically,' says Burton, 'the region recognised by these new antibodies is potentially a much more accessible site for vaccine design.' But if people who are infected with HIV are alreading making these antibodies, why are they still carrying the disease?

'Preventing infection in the first place is a very different challenge than ridding the body of established HIV, which integrates itself into the human host's DNA, making it much harder for the immune system to detect. The fact that patients can make these sorts of antibodies - and we got this result from just the first patient we studied - is really encouraging because it suggests that a vaccine should be able to do the same.

So, in someone who is not infected, these sorts of antibodies [produced by a vaccine] should be protective.' The next step will be for the team to continue to use their 'brute force' screening-based approach, now that they know it works, to track down more neutralising antibodies, and the viral sites they recognise, to produce a vaccine that can protect against the widest range of HIV strains.

- Previous Virus linked to prostate cancer

- Next Steel Velcro

Comments

Add a comment