A series of pits dotted across the surface of comet 67P-Churyumov-Gerasimenko, currently being scrutinised by the Rosetta spacecraft, point to a hollow interior, scientists announced this week.

scientists announced this week.

With a shape resembling a rubber bath duck measuring four kilometres across, 67P is hurtling through space at about 120,000 kilometres per hour.

Keeping pace with it is ESA's (the European Space Agency's) Rosetta probe, which was launched more than a decade ago to intercept the comet in 2014 and monitor its path as it curves Sun-wards through the inner solar system.

Rosetta is equipped with a range of instruments including a system called OSIRIS (Optical, Spectroscopic, and Infrared Remote Imaging System), which has enabled scientists to scrutinise the surface of the comet's body in detail as it spins beneath Rosetta at a distance of just 30 kilometres.

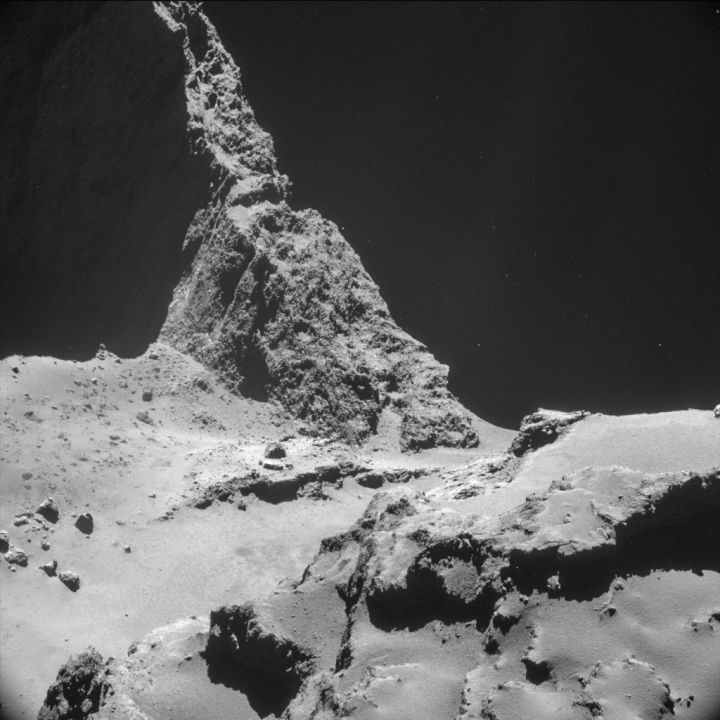

A striking feature to emerge was a series of at least eighteen sharply demarcated circular pits, each about 200 metres in diameter and 180 metres deep.

The pits are grouped into clusters and are clearly not impact craters. Some are also active, issuing jets of dust, and in the near-vertical walls on the pits large, metre-diameter cobbles are visible giving an intriguing inside into the interior structure of the comet.

Scientists had hypothesised that the pits were the results of volatile materials, warmed and driven off by the Sun's heat, escaping into space around the comet.

However, 67P has spent very little time this close to the Sun in its lifetime. In the 1950s it passed only about as close as Jupiter. Here it would be too cold to produce outgassing on a scale sufficient to account for the formation of the pits, each of which would require the ejection, the ESA team estimate, of a million tonnes of material.

Instead, the team speculate that these dramatic pocks are sinkholes and correspond to locations where material has fallen into voids or caves inside the comet's nucleus.

These spaces could have been present since the comet first formed, or might occur when volatile chemicals sequestered inside the comet, perhaps warmed by an internal heat source, escape to the surface leaving behind a space covered with a progressively thinner "ceiling" of supporting material.

This would explain why the pits are all roughly the same size and shape and grouped into clusters.

The findings are important because comets like 67P, which comes originally from the Kuiper Belt region of the solar system where Pluto also resides, are the solar system equivalent of chemical time capsules.

Captured within is a cross-section of primordial building blocks from which our solar system was assembled.

This unique insight into the interior of a comet, which is published in Nature this week, therefore also provides a valuable insight into some of the processes that these chemicals went through as the solar system assembled itself, 4.56 billion years ago...

Comments

Add a comment