Scientists have solved a long-standing mystery relating the structure of the placenta, the lifeline that connects mother and baby during embryonic development. For over 100 years anatomists have been scratching their heads trying to explain why, despite the function being the same for every animal, the placentae of different species were so dramatically different in structure.

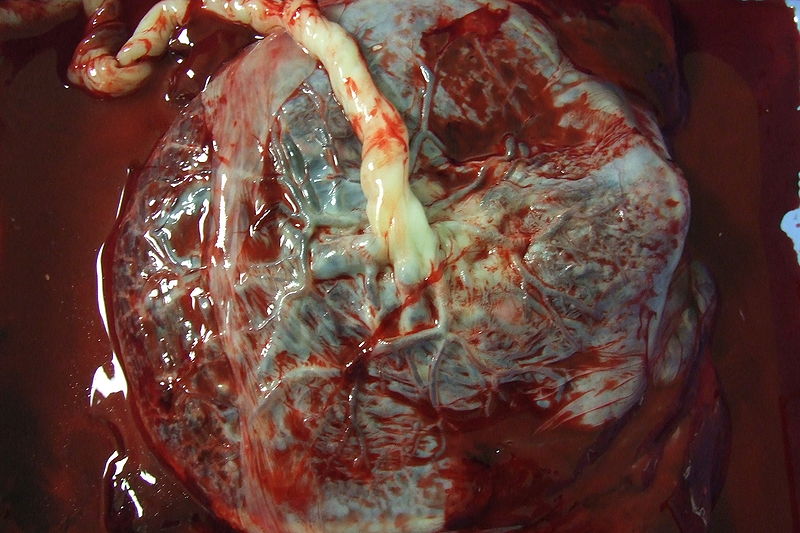

Now two Durham University scientists, Isabella Capellini and Robert Barton, writing in the journal The American Naturalist, think they know why. Their study compared 109 different animal species, including humans, taking into account the size and length of gestation of each animal as well as the stuctures of their corresponding placentae. What they found is that the simpler the structure of the placenta, the longer the gestation. So animals like a human or an ape, which have relatively simple placentae comprising just "fingers" of foetal tissue projecting into the wall of the uterus to contact maternal blood, tend to have a longer gestation, while species like dogs and leopards, which have relatively short gestation times, have extremely complex and highly folded "labythine" placental structures.

they found is that the simpler the structure of the placenta, the longer the gestation. So animals like a human or an ape, which have relatively simple placentae comprising just "fingers" of foetal tissue projecting into the wall of the uterus to contact maternal blood, tend to have a longer gestation, while species like dogs and leopards, which have relatively short gestation times, have extremely complex and highly folded "labythine" placental structures.

This latter configuration provides a very high surface area through which nutrients can be picked up by the developing foetus, while the simpler stucture adopted by humans have a lower surface area and hence a more limited rate of nutrient provision to a baby, prolonging the gestation. Why this is important is that it reflects the metabolic cost of pregnancy and is probably a protective mechanism by which a mother controls the resource conflict between her needs and those of the developing baby. Now this relationship is understood, Robert Barton points out, "it will be interesting to track down the genes involved and this will inevitably have clinical consequences too, informing our understanding of pregnancy-related conditions like pre-eclampsia."

Comments

Add a comment