pTry to conjure up the idea of a mountain lion happily running along on a  gym treadmill. It's hard to imagine. But with a lot of patience and a lot of meat, it was made a reality.

gym treadmill. It's hard to imagine. But with a lot of patience and a lot of meat, it was made a reality.

Mountain lions, also known as wildcats and pumas, are native to America, ranging from Canada all the way to South America. They are solitary and shy by nature and are largely nocturnal, meaning they are mainly active at night. This makes research into their behaviour very difficult, and means biologists can only observe them for a very small fraction of their daily activities. Whilst not currently endangered, they are increasingly coming into conflict with humans due to entry into their habitat, and their population numbers may suffer as a result of our land-use.

So why is putting a puma onto a treadmill useful? Research into energetics can give us an insight into an animal's 'energy budget', specifically how many calories they need to not only sustain themselves and survive, but also to reproduce. This has potential conservation applications.

The study, published in Science this week, involved a team from the University of California, Santa Cruz, looking into energetics, with regards to how much energy the wildcats expend on a variety of behaviours, from walking, to running to pouncing and making a kill.

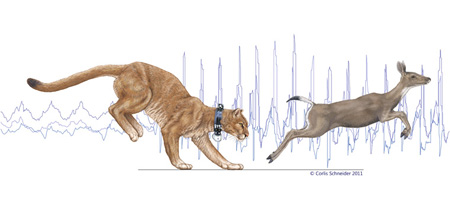

Both captive and wild mountain lions were fitted with high-tech collars with built-in GPS, to track their position, and accelerometers, devices that detect changes in force when the animal moves from vibrations and motion.

From the data trace, Professor Terri e Williams, one of the lead scientists of the study, could match the peaks of movement and time stamps to identify what the cats were doing during the day - essentially creating a diary of a day in the life of a wildcat. Williams also calculated oxygen consumption, to ascertain the energy costs.

e Williams, one of the lead scientists of the study, could match the peaks of movement and time stamps to identify what the cats were doing during the day - essentially creating a diary of a day in the life of a wildcat. Williams also calculated oxygen consumption, to ascertain the energy costs.

Williams likens the collars to human pedometers that tell you how many steps you've taken. They are just "a very fancy version of this but for a wildcat."

The accelerometer data show that the wildcats are not capable of sustained high-energy movement, but instead resort to brief bursts of energy in a short time to overpower their prey during a pounce and kill.

The findings also revealed that they can adjust the amount of energy they invest in the pounce, relative to the size of the prey, which can range from small racoons to full-grown deer far larger than themselves.

Williams is interested in next investigating how habitat fragmentation and human land-use are affecting the wildcat's energy budgets, and the next step of the research aims to delve deeper into the potential effects.

The collar technology can also be used on a range of other species. "These collars can tell us about wild wolves and lions, and even elephants and polar bears. I just find that so exciting" says Williams.

Knowledge of animal energetics can have implications on the development of wildlife management plans and conservation policies. Understanding the energy requirements of endangered species will be critical in the future if conservation efforts are to be successful.Listen to the interview with Professor Williams here:

Link to the University of California, Santa Cruz video of the treadmill training: http://youtu.be/jWZOmD5uerQ

Comments

Add a comment