For the first time, scientists have used genetic engineering to reprogramme immune cells to successfully eliminate tumour cells in one form of  human blood cancer.

human blood cancer.

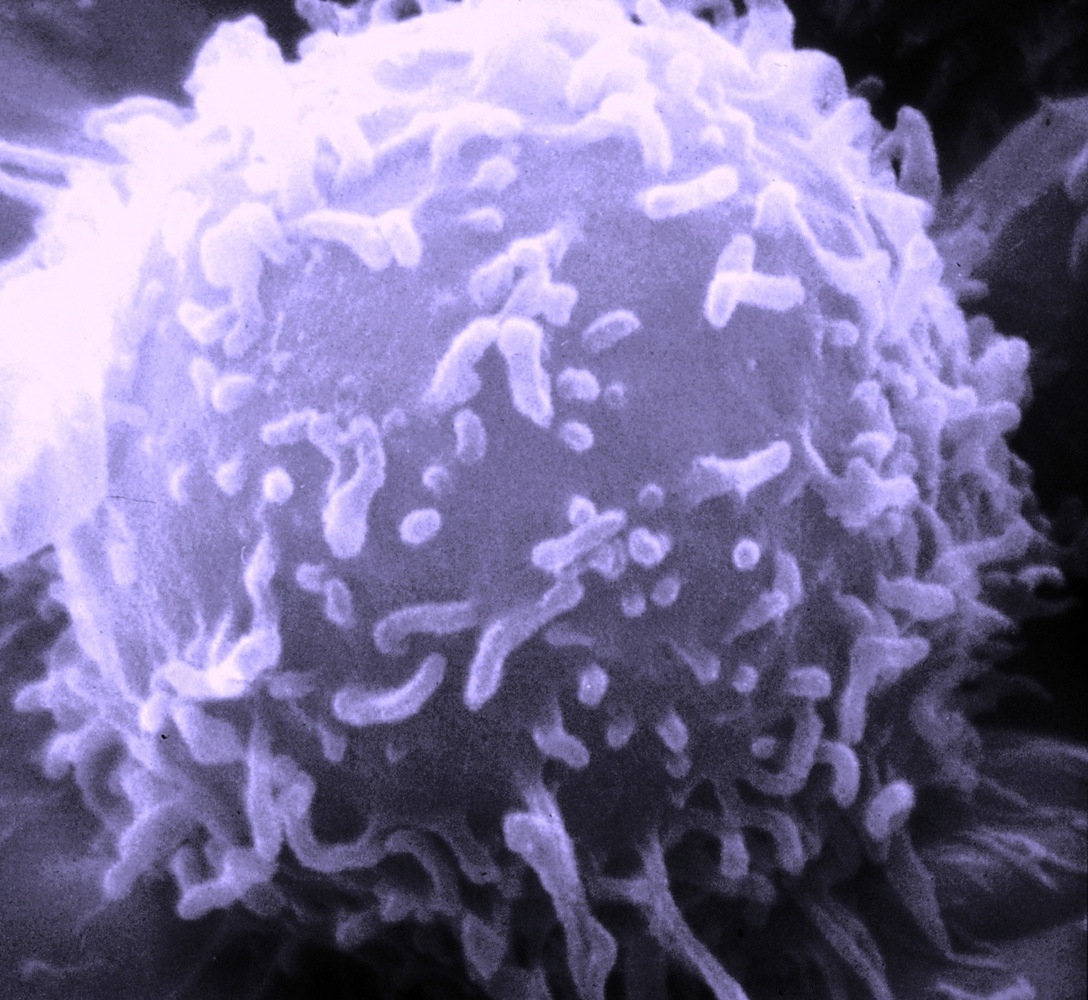

Writing in Science Translational Medicine, University of Pennsylvania scientist Michael Kalos and his colleagues collected T lymphocytes, a form of white blood cell, from three patients suffering from the disease B cell lymphocytic leukaemia (B-CLL).

In cell culture, a modified virus similar to HIV was used to add to the T cells genetic sequences encoding a signal called 4-1BB, which encourages active T cells to proliferate, as well as an antibody-like structure that could selectively recognise a chemical marker called CD19 that is expressed by the malignant B cells.

Between 10 million and 1 billion of the reprogrammed T cells were reinfused into each of the patients, in whom they persisted at high levels for at least 6 months, relentlessly hunting down and destroying the leukaemic cells in both the blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes.

Follow up tests showed that each infused T cell destroyed at least 1000 leukaemia cells, leading to the destruction of an average of over 1kg of cancerous tissue in each of the patients, two of whom went into complete remission following the therapy.

Previous attempts to use this sort of adoptive immunotherapy, as this approach is known, have been frustrated by the poor long-term persistence of the modified T cells in circulation. This allows the underlying disease to "escape" again, triggering a relapse.

But the researchers believe that the key to their success in this case was the use of the additional regulatory 4-1BB component, also known as CD137. By including this, they think, the modified T cells are stimulated to multiply as they fight the disease, helping to prop-up their numbers.

It's not all plain sailing though. Whilst targeting CD19 ensures that the modified T lymphocytes attack only B cells, this means that healthy, non-cancerous B cells are hit too. And as these cells play an important role in immune defence, including producing antibodies and providing a stored "memory" of infections fought previously, their loss can leave patients vulnerable to infection. This could be avoided in future by developing ways to target the T cell attack exclusively to the malignant cells, but this is still some way off.

It's also important to emphasise that the present trial involved just 3 patients who have been followed up for just under a year so far. The study results therefore need to be interpreted cautiously, although with optimism.

Comments

Add a comment